There are a few quirky constants that show up in Frank Kidner’s photographs of the Syrian countryside. He snaps errant debris that he describes, in a sharp script penned along the rims of his slides, as “decorative rubble.” He photographs children playing among the ruins. He looks for wild flowers, anomalous blooms in the dry hills of the Belus Massif.

Though none of these is the main focus of the collection. A self-described shutterbug, Kidner made six trips to Syria in the 1990s to document, in vivid color photography, the architectural remains of the country, eventually narrowing his focus to the Belus Massif, a limestone plateau in northwestern Syria. The final collection, which numbers more than nine thousand slides, was recently acquired by the Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives at Dumbarton Oaks.

The acquisition of Kidner’s collection is significant for a number of reasons. In addition to more than doubling the ICFA’s current holdings of Syrian images, it documents in rich detail countless sites, many of which have been fundamentally altered or completely destroyed in the years since Kidner’s photographs were taken. The collection’s vast scope also makes it a fundamentally adaptable resource, capable of being utilized in any number of projects, and the images themselves are beautiful and crisp, ripe for perusing.

The images center on the Dead Cities, a group of around seven hundred former settlements situated on the Belus Massif that exhibit a wealth of well-preserved architectural remains. So called for their abandonment in the eighth through tenth centuries, the Dead Cities provide a unique vision of late antique rural life, one that was remarkably prosperous and trade-driven, though not quite urban. As a result, the region serves as an excellent location for the study of largescale transition.

Kidner initially became interested in the Dead Cities after his first trip to Syria in 1993, which was largely a sightseeing excursion. Returning to the states and his professorship at San Francisco State University, where he has taught classes on the early history of Christianity, Kidner began to research work that had been done on Christianity in the area. In the process he stumbled upon a photograph-laden study written by the Princeton professor Howard Crosby Butler in the early twentieth century that catalyzed his interest: “It was very fragile, very brittle, down on a triple folio shelf—I checked it out and kept it at my home for years and years.”

Kidner’s photographic work in the region was driven by a desire to investigate the introduction of Christianity and the ways in which it adapted itself to the region’s preexisting architecture. “I tried to look at the built environment as a source for understanding how it was that Christianity managed to insert itself into these communities,” Kidner says. Since the villages of the Belus Massif were built around the same time that Christianity was making inroads into the region, their physical remains afford a unique perspective on the process of conversion.

Kidner’s fieldwork and photographs eventually resulted in a paper, “Christianizing the Syrian Countryside: An Archaeological and Architectural Approach,” which serves as an illuminating entrée into the collection. In essence, the paper argues that the manner in which preexisting structures were converted into Christian churches quite clearly delineates local attitudes toward the new religion.

Part of Kidner’s anthropological approach posits that architecture is a peculiar form of language, one that is ever-present and wheedling, suffusing the lived space of the environment and sending out ideological information constantly. This sense of totality also pervades his slides, which systematically document structures from every angle and distance; focused attention is given to each tumbled pediment, every shattered column.

St. Simeon’s Monastery, a sprawling complex located about twenty miles northwest of Aleppo, receives just such a treatment from Kidner’s lens. It is captured at a distance, a mere smudge on the horizon; its facades are shot, as well as its baptistery and the innards of these structures; bemas and transepts are painstakingly documented; apses and friezes and narthices are snapped up in turn. Over three hundred slides are dedicated to the compound’s details, many of which are treated from multiple angles and in multiple lights.

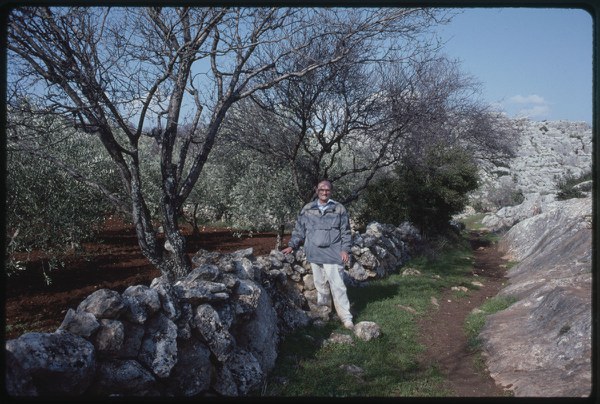

Beyond the temples and farmsteads lie the fields, which Kidner captures now and again, snapping the deeply lichened stretch of an old stone wall or handing the camera off to pose by a beaten track running along and through the stony heights of the massif. There is a timelessness to the landscape and its simpler elements that at times runs counter to Kidner’s other errant shots, which often capture fleeting phenomena embedded among the ruins.

“There are two things that are sort of off the track as far as the built environment is concerned,” Kidner says. “You have the hollyhocks and pictures of wildflowers—I’ve been a gardener all my life—and then you have the kids. And looking back now, I think in a way they’re the most poignant aspect of the collection. God knows they’re all grown up now; God knows what has happened to them.”

In the course of his travels, Kidner met the children—or, as the scribblings on his slides deem them, “moppets”—of the region. “I’d start photographing, and these kids would pop up, and trail around after me, and ask if I could take a picture of them.” Often enough, his visit to the site would end with an improvised shoot, the kids bunching themselves together against ancient walls buttressed with concrete or else standing aloof and alone, a little wary of the man with the camera, a little curious about the device itself.

All in all, Kidner’s collection straddles the gap between the personal and the historical. Images of St. Simeon’s Monastery rub shoulders with those of thick-stalked, vibrant hollyhocks, while imposing stone walls contrast with the sunsets Kidner describes as his “Condé Nast” photos. Even in the collection’s ostensible focus—the architectural images—it’s not simply academic thoroughness that drives the photographing of the built environment, but curiosity, and a predisposition to the contemplation of ruins.

Look even briefly at Kidner’s shot of arcosolia (recesses, typically above ground, used for entombment) in the mortuary chapel at St. Simeon’s monastery, and it quickly becomes clear that a somber mood has overtaken the documentary drive; the gaping hollows and the mineral stains bearding the walls evoke a sense of ancient emptiness, one that is both difficult to fathom and hard to shake.

Kidner’s own old preoccupations emerge in these moments. “I certainly had an interest from the time I was quite a small kid in seeing old things, and not necessarily old things in museums,” he says. “I would pester my parents, when we were out on a drive, to stop if there was an old Wells Fargo station, or, in California, a few Gold Rush things.”

It’s not difficult to picture Kidner pausing over the crossed lintels and intricately carved stonework strewn about the grounds at Qirqbizeh, a site west of Aleppo. The images that emerge are of stones among stones, singled out more than anything else for the delight they give, the mandala-like finery set into their weathered faces.

In short, Kidner’s collection is alternatingly comprehensive and composite; it obsesses over monumental arches one moment and drifts off among the flowers in the next. The vivid reality of its shots, charged with an almost unearthly color, brings to life a moment in time that is frequently undercut by a sense of absence.

In a distant image of St. Simeon’s taken from the nearby site of Takleh, the zigzag of a road dominates the background, while a stone wall interrupts the foreground. In the middle of the image spread fields that were once worked and might be worked still. It is a view of many worlds held together by space and the miracle of a well-composed shot.