Consideration was given, first and foremost, to the trees.

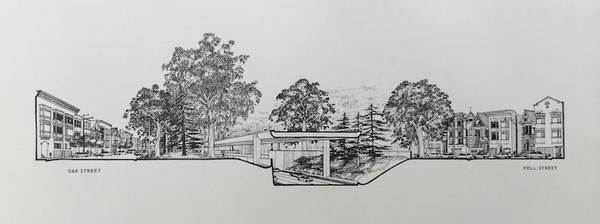

As the fledgling firm of Lawrence Halprin & Associates drafted its designs for the San Francisco Panhandle freeway, a decided bias began to appear. In their renderings, vigorous trees occluded the hypothetical tableaux and the proposed manmade structures that should have been centered. This choice subtly asserted the primacy of the individual’s experience of the space. It was, in a way, a revolt.

As Margot Lystra explained in her recent Mellon Midday Dialogue, the debate surrounding the decision to build a freeway through the Panhandle park in San Francisco managed to anticipate later shifts in the conception of urban space—including turns to environmentalism and a focus on collective experience that have come to be seen as central to urban planning.

Though “freeway” and “cultural catalyst” aren’t typically synonymous, Lystra, a PhD candidate in the History of Architecture and Urban Development at Cornell University and one-month research award recipient in Garden and Landscape Studies, sought to weld the terms together by tracing the hullabaloo around San Francisco’s freeway plans in the early 1960s. Much of her talk followed the efforts of the aforementioned Halprin & Associates, which was founded by Lawrence Halprin, a landscape architect whose projects pioneered attention to human scale and social impact. As Lystra described it: “They were trying to develop ways of thinking about the space that were technical and actionable, but that still captured the sensorial, lived experience of being there.”

Under the aegis of Halprin’s firm, the urban fabric of San Francisco was quickly redefined in terms of community. In a report on the aesthetics of urban freeways, Halprin & Associates shifted the project’s focus to the environment around the freeway, rather than the structure itself. Defining the urban texture of the area in broad spatial categories, the firm’s newly developed conception of the environment as “something lived,” rather than a dry spatial descriptor, began to assert more control over their designs.

When state engineers eventually got their hands on the report, Lystra said, they were careful to remove Halprin’s use of the word “environment,” though they weren’t able to elide his views on space and design, which permeated the project. Whenever he had the chance—in meetings, at work—Halprin used and emphasized the word “environment,” reminding those around him of the vetoed lodestar that still guided their work.

Eventually, as public hearings got under way and the public learned of the proposed plans, a staunch resistance emerged. Editorials in local newspapers bemoaned the loss of trees that would accompany the freeway’s development, wildly estimating the numbers to be chopped down, while “Save the Park” rallies were held, replete with signs, marching, and maudlin folksingers.

At the second public hearing on the issue, community members began to articulate “surprisingly complex functional-spatial connections,” as Lystra put it. Some attendees argued that the park’s racially integrated playground, one of the few in the city, was a powerful source of unity in the community. Others touched on the critical role the park’s trees played in dampening the coastal winds that roared over the city. When the displacement of black families that would occur with the freeway’s construction was broached, it caused one community member to solemnly proclaim: “If you’re gonna plan, plan for all of us.”

The freeway plans were eventually scrapped. Lystra’s talk, however, was less interested in the mechanics of revolt than the theoretical reverberations that ran through the country in the 1960s and 1970s as more and more cities, inspired by the San Francisco debacle, began to sideline their freeway development plans.

As Lystra described it, communities across the nation, aided by the discourse of the San Francisco debates, began to view the urban milieu as collective and fundamentally shared space. It could no longer be considered a conjunction of discrete structures, but rather became—had to become—“a great functioning whole.”