By Eric Nemarich, second-year graduate student in History and intern for Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library

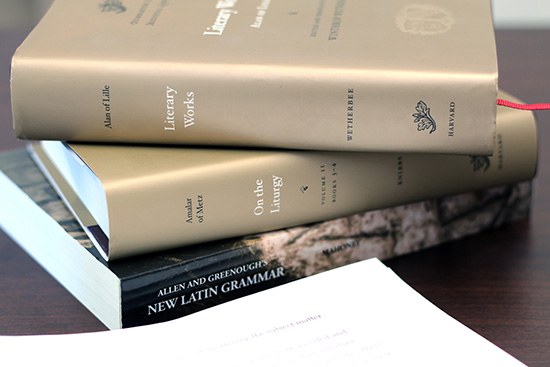

The Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library is not a physical set of stacks. It is, rather, a publication series, an “ideal library” of affordable, portable, elegantly bound, and scrupulously edited volumes of medieval texts accompanied by English translations on facing pages. So far DOML has tackled texts in Latin, Greek, and Old English, and I have heard rumblings that more vernaculars are on the horizon. The Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library aims to make the bountiful and bizarre universe of medieval literature available to a varied readership, and to that end its translations are rethought and refined virtually ad infinitum. This is where I come in, appearing in the invisible interstices of the editing process—fixing a misplaced modifier here, adding a comma there, at times offering my thoughts on a troublesome passage. Over the past three weeks, I’ve cultivated a love-hate relationship with “Track Changes.”

In that time, I have spent dozens of hours becoming closely acquainted with a rhetorical treatise penned by an anonymous fourteenth-century Englishman. As I’ve absorbed and digested chapter after chapter (sixteen in all) of medieval rhetorical theory, one single, troublesome adverb has transfixed my mind: inartificialiter. As used in the treatise, it can be approximated in English as unskillfully or inelegantly. But I have proposed to translate it with a different word, one that, like its counterpart, does not appear in the Oxford English Dictionary and receives a reproachful red squiggle in Microsoft Word: inartfully.

The word has a checkered and revealing past. In contemporary English, artful has come to be synonymous with clever or even conniving, while inartful has forked into subtly differentiated meanings: in legal writing, it has carried the suitably blunt sense of “poorly written”; but in the sphere of politics—ever on the mind of a Georgetown resident—it has served as a convenient euphemism for tactless statements made in earnest. This is generally unsurprising. Rhetoric and its attendant vocabulary, including words such as inartful (and for that matter inartificialiter), have been closely aligned with law and politics for millenia.

What strikes me as remarkable is the seismic cultural shift that rhetoric has experienced through the centuries: once enthusiastically cultivated by ancient, medieval, and Renaissance scholars, it has lately taken on a distinctly pejorative cast, as a reference to words spoken or written with no real meaning. We have erected a barrier between art and artifice, between literature and “mere rhetoric.” Words like inartfully bear eloquent witness to this change. I stand by my proposal—which remains, after all, just a proposal—because a translation can and often should play upon multiple and even contradictory meanings, inviting readers to delve into the strange, ever-shifting histories of words. The languages we speak today and the languages of the distant past are bound by entangled threads that form intricate tapestries. For medieval rhetoricians, language afforded the opportunity to beautify reality. Our translations operate in much the same way, bringing the grace of modern language to ancient texts and setting their complex beauty in ever higher relief.