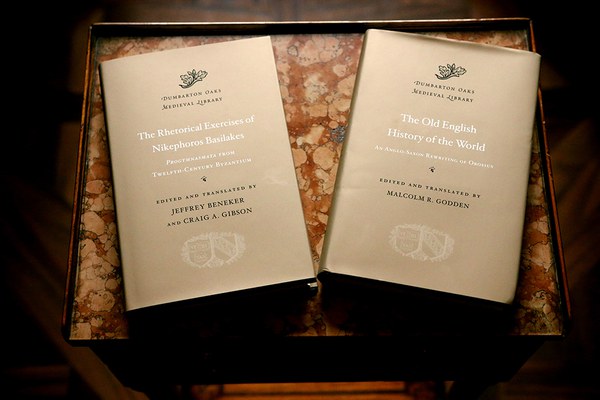

In October, the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library will add two new volumes to its catalog of historic texts, both of which are concerned, either directly or obliquely, with the power of rhetoric and the act of rewriting.

The Rhetorical Exercises of Nikephoros Basilakes

The Rhetorical Exercises of Nikephoros Basilakes, written sometime in the twelfth century by the eponymous Byzantine aristocrat and pedagogue, encapsulates a new trend in education that arose in the medieval period. Short and rhetorically dense, the exercises were meant to replace the intensive study of complete ancient texts that had dominated aristocratic education for more than a thousand years.

The exercises, or progymnasmata, are presented in seven categories of distinct rhetorical styles: fables, narrations, maxims, refutations, confirmations, encomia, and ethopoeiae. By far the largest portion of the book is taken up by the ethopoeiae, speeches delivered by historical or mythological figures in which the personalities respond to a challenging situation, and in the process reveal a sliver of their character, a glimpse of their emotional state, or both.

Though ostensibly didactic, the exercises, crisply translated by Jeffrey Beneker and Craig A. Gibson, are also consistently entertaining and offbeat. In their idiosyncrasy, they aid the impression, established by the volume’s introduction, that Basilakes was a shameless self-aggrandizer. “According to his own testimony,” Beneker and Gibson write, “Basilakes was a very successful teacher, whose popularity attracted the envy of the patriarch.”

Besides elaborating the field of schedography (the method of studying short texts), Basilakes is notable for the “artistic blending of pagan and Christian sources and worldviews” that informs his compendium; a Biblical story is just as likely as the tale of Phaëton to prove the author’s point.

Reading the Rhetorical Exercises, one quickly senses that Basilakes was a clever man. His exercises blur thematic and tonal boundaries, as if he wants to assure readers that complexity can arise even in his truncated, prefabricated texts. The ethopoeiae in particular touch on themes as diverse as art and nature, chastity and desire, and the theatrical grounding of day-to-day existence.

There is, too, a wry bluntness, most prevalent in his fables, that can seem off-putting if one expects to find an Aesopic neatness and refinement in the exercises. For instance, Basilakes writes of a lion who becomes enchanted by a beautiful girl and asks for her hand in marriage. At first the story seems a fairy tale, until reality sets in, and the lion wonders if the girl’s father will consent to being called the “father-in-law of a lion.”

Practical, humdrum matters, absurd as they may seem, take over. The arc of the fable is wholly unpredictable, and the eventual moral of the lovelorn lion’s tale—“Do not trust your enemies too readily”—is so broad that the tale that precedes begins to seem more of a gymnastic experiment, as though Basilakes were flexing his creative powers, attempting to see how strange he can make the elaboration of a commonplace.

The Old English History of the World

In a similar vein, The Old English History of the World, edited and translated by Malcolm R. Godden, exhibits another author confident in his refashioning of ancient tales.

Orosius, a scholar and cleric, wrote his Seven Books of History against the Pagans in the early fifth century. Similar to Augustine’s City of God, the Seven Books sought to rebut claims that Rome’s decline had been caused by the abandonment of traditional paganism.

Nearly five hundred years later, the chronicle was translated into Old English by an anonymous author (or authors)—though “translated” is a generous term. Readers who pause over the table of contents may note, for instance, that Orosius’s famous Seven Books have been whittled down to a less imposing six. When the anonymous Anglo-Saxon—whom Godden, in his introduction, dubs “Osric”—produced his work in the tenth century, he didn’t so much translate Orosius as revise, excise, and thoroughly transmute the text.

Assuming in his readership a familiarity with Roman history and ancient matters, Osric retained a basic description of events from the Seven Books, while cutting liberally from Orosius’s commentary. At other points, he embellished, inserting dramatic speeches on a whim. All in all, Osric’s alterations are best summarized by the phrase “imaginative dramatization,” as Godden contends. Motives, outcomes, and explanations are added for color and detail.

Among Osric’s evident fascinations were military strategy and the customs of other cultures. And yet, while he delights in describing the ploys and plots of various wily generals, he also makes a point of bemoaning the terrors and tragedies of war. At one point in his history, in a fitting flight of fancy, the city of Babylon plaintively describes its own fall.

Osric revels in these peculiarities. While his narrative strategies may be lively and imaginative, the details he chooses to highlight—strange goings-on that are nevertheless dealt with objectively—form the backbone of the text. In writing of the burial practices of the Ests, a Baltic-region tribe often associated (whether accurately or not) with the modern-day region of Estonia, he describes, simply and with light wonder, what might be magic, or simply misunderstanding:

It is the practice among the Ests that everyone, whatever their country, must be cremated. If a single bone is found unburned, a heavy penalty is exacted. Among the Ests there is a community that can make things cold. The dead bodies lie uncremated for so long without rotting because these people create a chill in them. If you put out two vessels full of ale or water, they make one of them freeze solid, whether it is summer or winter.