We’re excited to announce the acquisition of two richly documentary colonial Latin American manuscripts. Featuring vivid illustrations and painstakingly detailed maps, the manuscripts contain enough material to satisfy a bevy of research interests and pursuits.

Relación de gobierno del Excmo. Sor. Virrey del Perú Frey D. Francisco Gil de Tobada y Lemus is a work whose extensive title does a good job of encapsulating its reach. Composed by Francisco Gil de Taboada y Lemos, the governor of the Viceroyalty of Peru from 1790 to 1796, as a detailed report on the operations of the colony, the text was meant to provide the viceroy’s successor, the Irish-born Spanish colonial administrator Ambrosio O’Higgins, with a guidebook of the region, in the hope of ensuring a fluid transition.

While such transitional reports were not uncommon, the sheer length of this piece and its comprehensive detail of colonial life makes the Relación de gobierno a sui generis acquisition. In it, carefully sketched charts abound, and while customary tabulations of population, natural resources, and tax collecting fill up much of the page space, Taboada y Lemos’s other inclusions offer insight into a naturally curious personality bent on fully educating his successor.

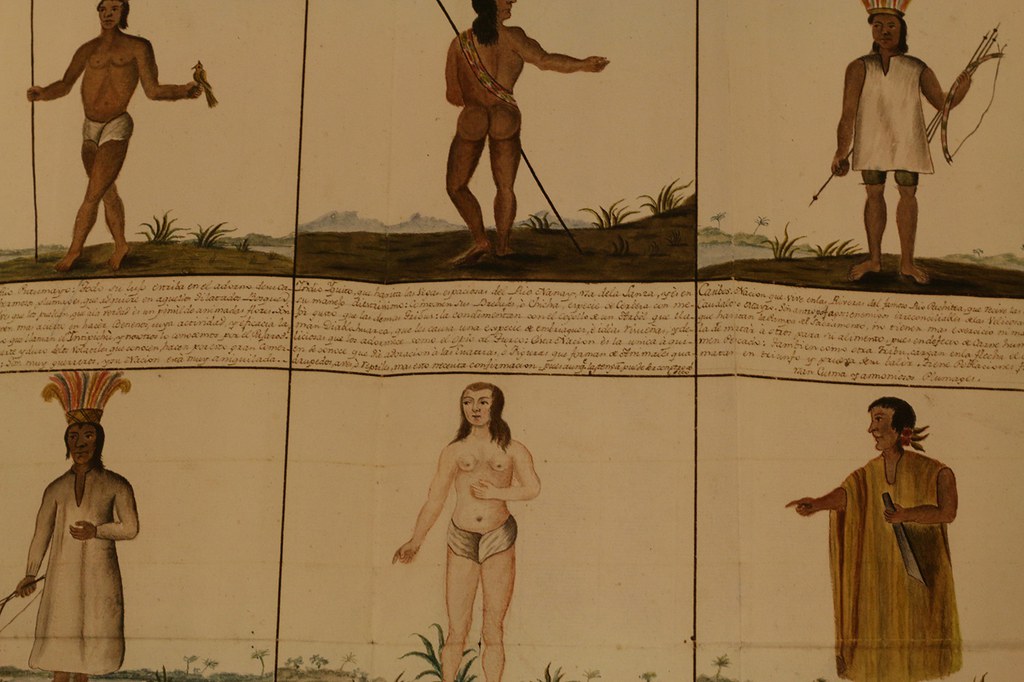

In addition to copious notes on the organization of the hacienda system and a discussion of the operation of the Inquisition in the Viceroyalty, for instance, Taboada y Lemos includes descriptions of Lima and of the commerce, mineral wealth, and architecture of Peru. Two well-preserved folding leaves reveal colorful fine-lined illustrations of the twelve indigenous ethnic groups of Peru as they were understood by the colonial power at the time. Variously cross-legged, bow-wielding, or pointing, garbed in light cloth or tunics or capacious furs, the detailed figures show differences chosen by the eye of the colonizer—a thin waist tightly bound in woven material; broad, muscular shoulders; pale white skin—standing out.

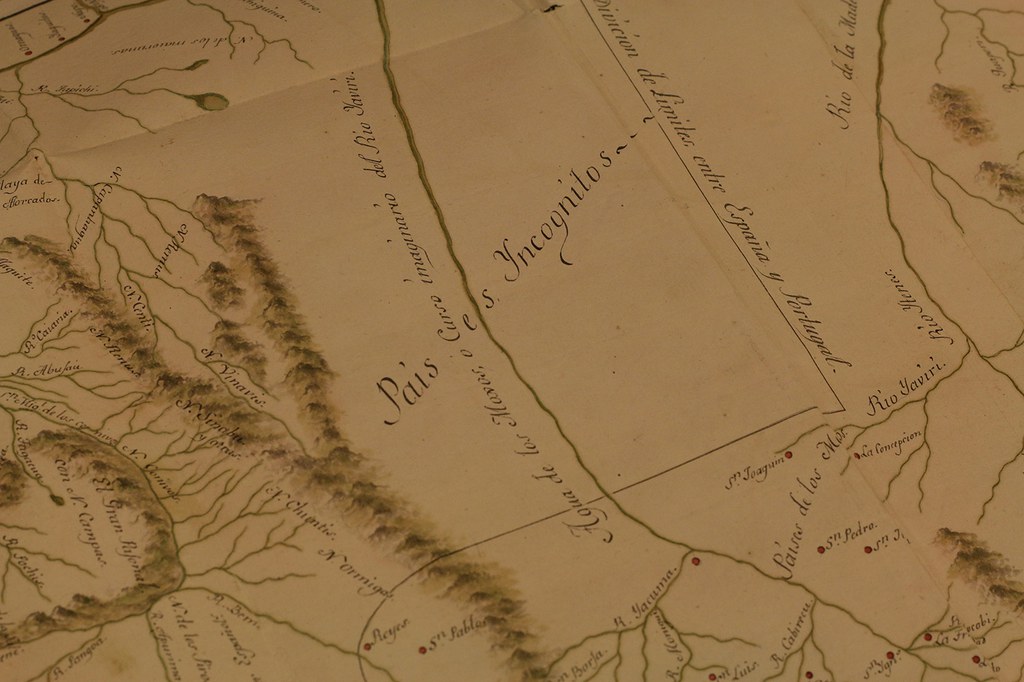

These images, executed by an unknown hand, are kept company by two fold-out maps at the end of the text showing the interior of Peru and the west coast of South America—depicted, curiously, horizontally. Drawn in lines faded, blurred, and expanded with age, the maps yet offer up the familiar names of mountain ranges, rivers, and cities.

The second manuscript is an eighteenth-century ejecutoria, a certificate that legally accredits the nobility of a family or individual. A petition of sorts, the ejecutoria is concerned with the title and coat of arms granted by Prince Philip II of Spain in a 1545 cédula (order or decree) to Felipe Tupac Inca Yupanqui and Gonzalo Uchu Hualpa as grandsons of the Inca emperor Tupac Inca Yupanqui. The provenance of this particular ejecutoria, however, is unknown.

In 1800, María Joaquina Inca, claiming descent from the royal families of Mexico and Peru, submitted a series of documents to the Council of the Indies, among them a similar ejecutoria now held in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville. It was common practice to create a copy when drafting these application packages in case anything should happen to the documents sent to court. Thus, it’s possible that the ejecutoria acquired by Dumbarton Oaks is the personal copy of Maria Joaquina Inca, or one that belonged to her family. Support for this theory comes from the illustrations in the ejecutoria, which remain bound to the text, meaning the manuscript was likely never held in a state archive, where images were often removed and catalogued separately.

The images in question are full-page illustrations. Two facing illustrations depict the coat of arms granted to the descendants of Gonzalo Uchu Hualpa and Felipe Tupac Inca Yupanqui. Crowns and helmets and castles blare out from a majestic red ground decorated with light blue vine-like tracery; a golden mask dangles from a chain formed by twelve pairs of crowned snakes. Notably, Inca symbols (crimson tassels, for example) are mingled with Spanish (the helmet, the castle, the crown).

A full-length portrait of Tupac Inca Yupanqui, flanked by two figures who are likely his descendants Gonzalo Uchu Hualpa and Felipe Tupac Inca Yupanqui, occupies a full page. Standing in a mountainous landscape, Yupanqui is garbed in a regal tunic (uncu), a headdress (mascaypacha) and a red cloak (llakota), and covered in gold—gold kneepads, headdress, earmuffs, and weapons.

The ejecutoria is a particularly valuable acquisition because it contains far more than document-collections of the sort typically do. Whereas many collections simply comprise the cédula describing the coat of arms to be granted once proof of lineage is provided, the Dumbarton Oaks ejecutoria contains the surrounding necessary documents—in short, it is claim and proof. Accordingly, scattered throughout the manuscript are carefully constructed stamps and signatures so elaborate they sometimes seem absentmindedly scrawled curlicues.

Both “new” manuscripts offer up an abundance of information that still needs much sifting. Francisco Gil de Taboada y Lemos’s report, oddly prolix and encompassing, provides a stunning firsthand account of the particularities of governing a colonial state, while the ejecutoria—thanks to the differences from its official counterpart, and its relation to previous applications—is ripe for comparative research and studies of the evolution of self-representation.