“When does bric-a-brac become a historically and socially valuable collection?” asked visiting medievalist Elizabeth Emery in her talk to an audience of faculty, staff, and Fellows at Dumbarton Oaks on June 17. Emery, a professor of French at Montclair State University and an expert on the reception of medieval culture in fin de siècle France, discussed the history of collecting ephemera, its relationship to academic study, and its future in the digital age in her lecture “Bricabracomania?: Collecting Medieval Ephemera from the Musée des Monuments historiques to Pinterest.”

The word ephemera, derived from the ancient Greek for day, literally means “lasting only one day.” The term describes a broad category of objects never meant to be preserved for posterity, including postcards, theater programs, menus, advertisements, and countless other relics of everyday life. For contemporary scholars, however, these objects—transfigured by the passage of time—are increasingly recognized as legitimate sources for historical study. Emery observed, “Where scholars used to practice largely image- and text-based study, many now examine the broader cultural field.”

These artifacts, Emery explained in an interview before her talk, have the potential to inform an increasingly democratic view of history. “There’s much more of an interest in looking at how the other half lives,” Emery said. “For a long time [scholars’] interest laid in elites, but looking at a broader swath of society brings curiosity about small objects, everyday objects, and how they influenced life in the past.”

In her own scholarly work, Emery has often used ephemera—from paperweights in the shape of Reims Cathedral to theater posters of Sarah Bernhardt in medieval costume—as a means to examine the ways in which nineteenth-century France understood the Middle Ages.

Emery also looked to the future in her talk: she suggested that sites like Pinterest, which allows users to “curate” images and text in virtual exhibitions, may be the twenty-first century’s version of Victorian scrapbooks and drawing rooms filled with bric-a-brac. She raised the question of the difficulties that today’s digitization of collecting may pose for scholars in the future. “We are recording very little of it, and links that were valid, say, last year, often don’t exist anymore,” she said. “It’ll be a huge challenge for future generations to know what was going on now and to come up with strategies for archiving or documenting it.”

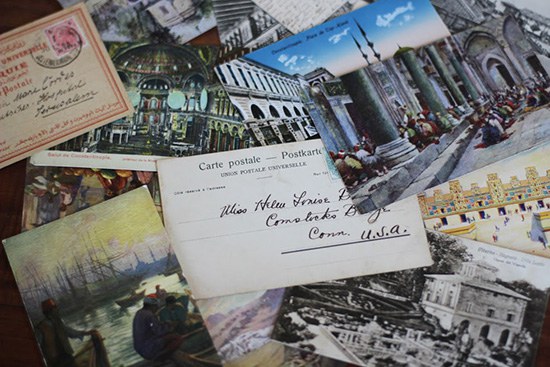

In his introduction to Emery’s lecture, Dumbarton Oaks Director Jan Ziolkowski praised her “frequent and imaginative use of [ephemeral] materials in her investigation of how the past viewed the still more distant past.” He also emphasized the relevance of Emery’s methods to the future of historical scholarship and to research institutions such as Dumbarton Oaks. Ziolkowski noted that Dumbarton Oaks has recently embarked on building its own collection of printed ephemera, beginning with postcards related to Byzantine, Pre-Columbian, and Garden and Landscape Studies. These acquisitions represent a foray beyond the rare books and precious works of art that constitute the core of the Dumbarton Oaks collections, but, according to Emery, they have the potential to offer new and valuable insights into the past. “Ephemera is not necessarily art in itself,” Emery said. “What’s important are the stories told about it and by it.”