A Dumbarton Oaks Project Grant in 2005–6 supported documentation and conservation measures that we coordinated in the archives and storage facilities of the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History of Peru, to rejoin the objects from Peru's most famous cemeteries with their original excavation data. While our initial work in archives and museum collections focused on the Paracas Necropolis cemetery groups, it also has had an impact on the data and conservation of materials from all sectors of the Paracas site, and can serve as a model for data recovery in other early 20th century archaeological collections.

Dr. Julio C. Tello led a team from the University of San Marcos and Peru's National Museum between 1925 and 1929 in research on a spectacular burial site on the south Pacific Coast of the Central Andes. They discovered a complex sequence of habitation, ceremonies and cemeteries, including the famous bottle-shaped tombs they called the "Paracas Cavernas" and a steep slope crowded with conical funerary bundles that they called the "Paracas Necropolis." Finely woven, brilliantly embroidered textiles spilled out into the light of day. From the beginning, Tello suspected their antiquity might be as much as 2,000 years – and radiocarbon dating later proved him right.

For their day, the excavations were carefully executed and quite well recorded. The inventoried materials were carefully packed in straw and wrapped in jute sacking for the bumpy truck ride back to Lima. Once located in a warehouse in the capitol city, Tello's team worked quickly to open some of the largest and best-preserved bundles to select materials that the Peruvian government intended to send to the 1929 International Exposition in Spain. All unwrapped materials were described and inventoried in "dissection protocols" according to Tello's methods and procedures. But the '29 stock market crash and Spanish Civil War led to many of these materials remaining in Spain, even to this day. Within the following year, Tello was replaced as director of the National Museum. Urgent salvage and research at other important sites claimed his attention. In the late 1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation supported conservation and new research on the Paracas materials. Once again, the National Museum team was preparing the maps, diagrams and photos and color illustrations for a major report on the Paracas site, when unfortunately Tello died in 1947.

On Tello's death the original records documenting the site, its structures and cemeteries, and the contents of each room and tomb were sealed and inaccessible to later researchers. His faithful assistant, Toribio Mejía Xesspe, had only partial records available as he worked to complete the planned publications, and his designated successor at the Museum, Rebecca Carrion Cachot, had only limited access for exhibit preparation and collections management. As a result, for more than fifty years the properly excavated Paracas Collection, poster child of Peru and heart of what is today the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History of Peru, was nearly as bereft of the contextual data vital for its interpretation as the many Paracas and early Nasca artifacts looted from sites in the region and dispersed in museums and private collections around the world.

This current initiative to reconstruct the lost information on the context of each object and each tomb emerged from a dialogue between art historian Anne Paul and the archaeologists of Peru's National Institute of Culture, including Director Luis Lumbreras and Carlos del Águila, then head of research at the National Museum. In 2001, thanks to initiatives organized by Ruth Shady at the Archaeological Museum of the University of San Marcos and Ada Arrieta at the Mejia Xesspe Archive at the Riva-Agüero Institute of Peru's Catholic University, it became possible to locate most of the original excavation notes and inventories, as well as records from later research. A call went out to museums and researchers around the world to collaborate on reconnecting all existing Paracas collections with their best-documented provenience.

We answered this call, and developed a project that included both archival research and work with the collections housed at the National Museum. Anne Paul's work with the Museum's textile department had focused on documenting the embroideries and other extraordinarily preserved textiles, whose brilliant colors, complex design and fascinating images of humans and fantastic animals had made this site famous. We have focused on documenting and preserving the diverse artifacts of plant and animal fiber, wood, bone, shell, basketry, hide and feathers that completed the regalia of each funerary bundle. Conservation and documentation includes the human remains, whose identity is vital to interpretation of the associated mortuary offerings. Thanks to the recovery of the lost archival data, objects found outside and adjacent to the funerary bundle also now can be systematically integrated into analysis of each mortuary context.

The project was developed in dialogue with the National Museum staff under the leadership of Director Carlos del Águila, and collections manager Fernando Fujita. The expert conservation team of the Department of Textiles developed the conservation procedures, working closely with curators and staff of the Department of Human Remains and the Department of Organic Materials. The project provided equipment and supplies in accordance with the budgeted requirements of each department. A modest stipend was provided to students specializing in archaeology, art history and physical anthropology, who received training and supervision from museum staff in conservation methods and documentation procedures. Materials treated ranged from feathered regalia to weaponry, from intact headdresses to skeletal remains. Preventative conservation measures designed for each group of materials have been integrated with careful comparisons between excavation records, museum records, and the object as it is preserved today, to confirm or correct its identification and integrate data from its original description and associations. All objects located and processed are placed in chemically stable storage containers that curtail the spread of biological agents and incorporate display of contextual information.

Our initiative has had greater impact due to parallel initiatives undertaken by curators and staff of every department of the National Museum. The Museum's library, a vital resource developed and maintained by librarian Benjamin Guerrero, is now adjacent to the Archives of Archaeology and History, where the Tello Archive, inventoried and conserved, is accessible to both museum staff and outside researchers under the supervision of archivists Merli Costa and Elízabeth López.

While our project has focused on preventative conservation of fragile organic materials, Maritza Pérez of the department of Ceramics at the same time has undertaken a systematic process of stabilizing conservation of ceramics from the Paracas site. The vast integrated database developed by curator Dante Casareto has facilitated our efforts to reintegrate data on ceramic offerings from the Paracas cemeteries with their original burial associations. In turn, our archival research allows us to place the Museum's sample of well-preserved vessels currently available for research and exhibit preparation in the context of the much larger number of vessels registered on excavation in an extremely fragmentary state.

Likewise, curator Julissa Ugarte has improved inventory and storage of Lithic artifacts. The improved museum laboratory facilities managed by curator Maria Inés Velarde in Metals facilitate material analysis of artifacts and x-ray of human remains, while our archival data provide data on their original disposition and subsequent treatment in the museum, as well as lost associated elements such as cordage for attachment, fragmented shafts or handles, cloth bundles, etc.

Archival work to date has provided substantial new information. Mapping the excavation sequence facilitates linking inventory data to cemetery context, and descriptions of changes in the excavation strategy are important for spatial analysis and evaluations of data quality. Original field notes supplement the published reports and permit a re-evaluation of Tello's initial published interpretations of the site. Dissection protocols resolve a thousand doubts about object provenience and the nature of the burials, and provide a new basis for future research, in which outside researchers and MNAAHP staff can restudy some mortuary assemblages and prepare to reinitiate study of funerary bundles that had been only partially examined. Above all, the new data prove that the Paracas cemetery populations were far less homogeneous that has been generally believed based on the published sources – evidence for social diversity that should inspire new research directions in study of the relationships among the Paracas, Topará and early Nasca traditions.

Information generated by this Project is currently being integrated into the databases used to locate tomb associations (located in the department of Human Remains), and contents of each funerary bundle (located in the department of Textiles). Photographic documentation of the artifacts will serve to protect the museum's collections and facilitate future research, as well as international collaboration in object documentation and exhibit development.

Ann Peters is continuing to develop a database to facilitate future study of artifacts and formal and spatial relationships throughout the Necropolis cemetery groups. Already, we are able to contribute data to support research on specific Necropolis burials and Cavernas burial groups being conducted by the members of the National Museum staff, as well as independent researchers such as Mary Frame and Delia Aponte. The intention of this project is to create a new platform, a common base of information for future research on these complex cemeteries and this fascinating moment in the history of the Andes.

We also hope that the Dumbarton Oaks project will serve as a model for future collaborations among museums, working together to recover lost data and generate new knowledge—opening new doors to the complex history and cultural achievements of Pre-Columbian societies of the Americas.

Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú: Textiles

Due to the substantial experience in treatment of fragile organic materials by the Textiles department of the National Museum, preventative conservation and storage procedures for the Dumbarton Oaks project were coordinated by curator Carmen Thays and conservator Maria Ysabel Medina, who established treatment and verification procedures, trained student assistants, consulted on procedures in the other departments and intervened directly in urgent or complex cases. Certain objects from other departments, such as headdresses in situ or fragile basketry artifacts, were brought to the Textiles department for conservation.

All objects were cleaned using distilled water and soft brushes. In the cases where mold or salts were present, cleaning included use of a dilute alcohol solution. In certain cases, there was recourse to the department facilities such as a stereoscopic microscope for identifying component materials and contaminants, a humidification chamber, and a freezer and fumigation chamber for eliminating biological agents. In cases where an artifact was found in extremely fragile or fragmentary condition, it was wrapped and loosely stitched to tulle fabric dyed to match its color.

Both digital and slide photographs were taken to record object identity and treatment. Research to confirm and correct object identity was undertaken parallel to the conservation process, and contextual and technical descriptions in the object registration were corrected where necessary. All treated objects were stored in groups according to their component materials, artifact categories and provenience information, to facilitate future monitoring, treatment and research.

A total of 103 hairpieces fashioned with human hair were treated in the Dumbarton Oaks project, including 27 pieces originally identified from the Wari Kayan (Necropolis) cemetery and 76 pieces from other parts of the Paracas site.

Among feather hair ornaments, fans and other feathered artifacts, 107 pieces were identified and conserved. These also included groups of miniature garments covered in yellow feathers, and several full size open-sided feathered tunics.

19 artifacts of animal skin were originally identified based on Textiles department records. Another 20 pieces were identified in the course of the project, for a total of 39 conserved skin artifacts that once formed part of warrior dress and funerary regalia. Other diverse pieces treated include tiny skin bags of powdered minerals and shields made of large cane panels interlaced with strips of camelid hide with a cordage handle.

113 pieces of vegetable fiber were located and treated. The majority were slings, and other vegetable fiber cords used as headdress elements or to bind the limbs of the person being positioned and prepared for the funerary wrapping process.

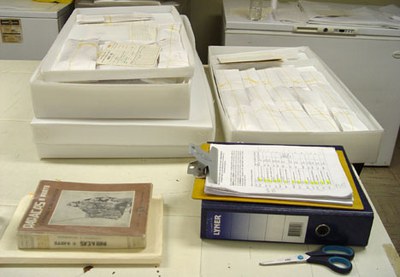

Storage boxes produced in this facility were constructed from sheets of corrugated polyethylene in groups of standard measurement for stacking in the Textile storeroom, folded and sewn to the precise shape and labeled using standard formats developed by the conservation and analysis team.

As information became available based on work in the archives, it was immediately incorporated into the procedures of work with the objects. Object identities were confirmed or corrected by consultation with central and departmental registries, inventories of storage areas, and published and unpublished studies of the artifacts. As the project developed, the department continued its ongoing project to reconstruct mortuary assemblages within the textile collection and built its own archive of copies of 'dissection protocols', narratives and inventories that follow the procedures established by Tello for unwrapping each funerary bundle.

While the Dumbarton Oaks project focused on contexts within the Paracas Necropolis cemetery groups, the Textiles department has gone on to apply the same procedures in work with materials from the Cavernas area and other collections.

Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú: Human Remains

The department of Human Remains is also the central location for storage of mortuary contexts, including intact or unwrapped funerary bundles. As a result, the information management and conservation issues faced by this department are extremely complex. Fortunately, curator Elsa Tomasto had already developed a substantial database to bring together information on the known provenience records, storage location and history of treatment, analysis and exhibition of materials in this department. Forensic anthropologist Melissa Lund and storage manager Carlos Murga provided additional expertise in training and supervising the student assistants who worked with the Dumbarton Oaks project.

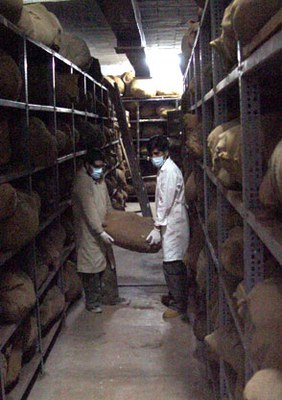

The department of Human Remains had achieved substantial improvements over the past ten years, including structural improvements in the vast storage structures and installation of climate control essential in Lima's humid environment, which is also subject to considerable yearly fluctuations in temperature. Cleanliness and order have been greatly improved, but due to the sheer number and crowded conditions, the location of all mortuary contexts has not yet been identified. Many of the Paracas funerary bundles were unwrapped and studied in the early 20th century, yet many of their components are still stored in this department as bundles wrapped in jute sacking.

Our project supported the priorities of the department of Human Remains, collaborating in moving mortuary contexts housed in a warehouse that needed urgent structural improvements, locating contexts whose whereabouts was unknown, reuniting and identifying the components of each Paracas burial, creating an inventory of the contents of previously opened funerary bundles, and transferring those human remains and associated artifacts to storage in polyethylene boxes. We also collaborated in providing a ladder and flashlights essential for confirming the location and identity of hundreds of Paracas burials crowded on high shelving in the dim lit storage facility.

All skeletal remains were cleaned using soft brushes. Particularly in the case of soft tissue preservation, minimal handling was an important component of the procedures. Previous wrapping materials, such as newspapers, were carefully removed. Soft and chemically stable support cushions were designed and constructed. Where mold or salts were present, cleaning included use of a dilute alcohol solution.

In cases where textiles and other artifacts were present, materials on the body were conserved in situ and cleaned if appropriate by the textile conservators, who also trained the student assistants in Human Remains in basic textile conservation procedures.

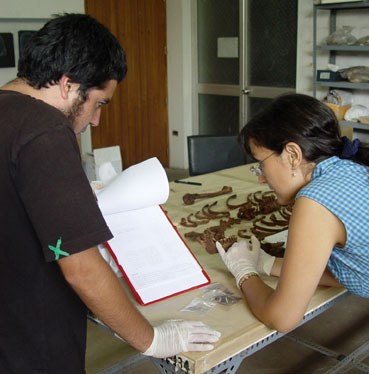

Artifacts already separated from the body were cleaned and stored separately, conserving all available contextual information. Both digital and slide photographs were taken to record object identity and treatment. Research to confirm and correct the attributions of both human remains and associated artifacts was undertaken parallel to the conservation process, and new registration records were developed for each context. All treated materials were stored according to their level of preservation and provenience information, to facilitate future monitoring, treatment and research.

Skeletal remains from the sectors of Paracas Cavernas and Arena Blanca. In many cases, skeletal remains had been sorted into cranial and post-cranial groups that did not carry original provenience data. In cases where inventory numbers or contextual information had been preserved on the bones they could be linked again to their excavated mortuary context. Refitting of skeletons confirmed the reconstruction of a number of individuals. The human remains were reunited in an improved storage context, and basic evidence for age and sex was recorded.

Among the Paracas Necropolis burials studied by Toribio Mejía Xesspe from 1967 to 1970, in several cases the head was stored separately from the body to facilitate future study of intact hair arrangements and headdress elements. In these cases, the separate storage arrangement was continued. After inventory, cleaning and protective conservation measures they were stored on padded trays to facilitate future observations without requiring handling of the human remains.

The reexamination of previously studied mortuary contexts was a moment of great excitement and interest throughout the museum, as each occasion provided the solution to many unanswered questions regarding artifact location and provided new data on the nature of the Paracas cemetery populations.

Systematic study of each reopened bundle included a thorough examination to provide improved data on the age, sex, and general health of the individual, as well as data on occupational stress and on the possible case of death.

Storage boxes produced in this facility were constructed from sheets of corrugated polyethylene in groups of standard measurement for accommodating and protecting a single mortuary context and to efficiently stack in the crowded warehouses. Each box was folded and sealed with a glue gun, then labeled using standard formats developed by the Human Remains team.

Our archival work was made available immediately to the department, to complement the substantial contextual information in their database by providing better information on the associated artifacts frequently located in bundles stored in Human Remains. As the project proceeded to the re-examination of previously studied funerary bundles, the department also built a library of copies of 'dissection protocols', narratives and inventories following the procedures established by Tello for unwrapping each funerary bundle.

While we were able to collaborate in work on only a small percentage of the Paracas cemetery populations housed in the department of Human Remains, the Dumbarton Oaks project served to address some urgent cases, establish new procedures and support the training of a new generation in the management of Peruvian museum collections of human remains.

As information became available based on work in the archives, it was immediately incorporated into the procedures of work with the objects. Object identities were confirmed or corrected by consultation with central and departmental registries, inventories of storage areas, and published and unpublished studies of the artifacts. As the project developed, the department continued its ongoing project to reconstruct mortuary assemblages within the textile collection and built its own archive of copies of 'dissection protocols', narratives and inventories that follow the procedures established by Tello for unwrapping each funerary bundle.

Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú: Organic Materials

The Organic Materials department of the National Museum has received the least attention and external funding of any department over the past 50 years. The quantity of organic material lacking a thorough inventory and adequate conservation and storage conditions was so daunting that until recently the museum staff focused their efforts in improving conditions in other areas. Fortunately, the Dumbarton Oaks Project coincided with a massive project of inventory, registry, cleaning and improved storage of organic materials carried out by a dynamic team under curator Manuel Gorriti and area registrar Milano Trejo. Our first phase of work in this department focused on material that already had been located by their team in their processes of inventory and reorganization of registered artifacts. As the project continued, we returned to the department on several occasions to work with materials that had appeared in the process of cleaning and registering artifacts whose location had been hitherto unknown, or whose Paracas inventory data had been lost.

The basic cleaning of artifacts of wood, bone and shell was carried out by the Organic Materials team. Artifacts with textile, feather and skin components were usually sent to Textile department for treatment and storage. Basketry and some gourd artifacts were treated by either the textile conservation team or by Rosa Martinez of the museum's department of Conservation and Restoration.

Of the polished staffs and tendon-bound staves originally inventoried at the Necropolis of Wari Kayan and the Arena Blanca/Cabezas Largas cemetery groups, we developed a detailed description and photographic record of a total of 51 examples located in the storage area. Subsequently, the department team has carried out the same process with the examples currently located in the exhibits area of the Museum.

An important sample of spear throwers and carved handles from Paracas are currently on exhibit in the Museo de la Nación; those present in the department of Organic Materials have been cleaned and moved to stable storage boxes. Until now, it has not been possible to locate the bundles of cane lances, a recurrent offering in the Necrópolis burials composed of a material subject to deterioration in open storage areas.

Most of the gourds from the cemeteries of Paracas were found in a fragmentary state on their excavation, and it is likely that most of them are still found among the diverse materials still located as mortuary contexts in the storage areas of Human Remains. Nonetheless, a sample of gourds from Paracas are located in storage in Organic Materials and it was possible to largely reconstruct three from the Necropolis, in the form of semi-hemispheric bowls. These gourds were photographed together with ten gourds of diverse shapes, coming from different cemetery groups at the Paracas site.

The large baskets typical of principal burials in the Necropolis mortuary complex have been found stored within bundles from a single funerary assemblage; probably the majority are still located in those bundles within the storage areas of Human Remains. The smaller baskets, typically part of the offerings that accompanied burials in all the Paracas cemetery groups, were often found in a fragmentary state. The sample present in storage in Organic Materials primarily comes from the Cavernas tombs, and consists of examples selected to create the basket typology developed by the National Museum team in the 1940s. At that time they were already incomplete, and there are clear indications of later deterioration caused by the presence of salts in the fibers composing the baskets and the absence of a storage area with climate control.

Eight of those small instruments called "sieves" by their excavators were located and recorded, a small sample, but which appears to represent most of this type of instrument registered in the excavation inventories. As several of them have lost the lettering with their original context or inventory, the research processes are still pending that will attempt to reunite each example with its original contextual information.

Another category of artifacts containing elements of plant fiber cordage that are located in Organic Materials are the shell body ornaments, generally necklaces and bracelets. Most have been found in a fragmentary state, and frequently they are present as collections of beads or worked shell. The most complete examples found in this department are mounted for exhibit. Although one of these should be transferred to a mount made of different materials, they are in stable condition and their future conservation is in the hands of the department staff and textile conservators. Artifacts of plant fiber that incorporate other textile elements and feather work have been transferred to the Textiles department.

Bone instruments, among them a collection of quena-type flutes from Paracas, have not received treatment in this project, as they are already in a process of study and conservation by Milano Trejo and the Waylla Kepa project. Nor have we worked in this project with the samples of offerings of vegetable foods and animal tissues located in glass jars in the department of Organic Materials, a process that should be carried out with the collaboration of specialists in the study of botanical remains and foodstuffs.

Storage boxes produced in this facility were constructed from sheets of corrugated polyethylene in different sizes to accommodate groups of staffs of different lengths, and in more standard measurement for other artifacts. The use of these boxes will facilitate monitoring for possible termite infestation, as well as isolation from re-infestation after treatment. They were folded, subdivided and attached with metal brads, then labeled using formats developed in collaboration with the Organic Materials team.

The massive improvements made in 2005–2006 in information, conservation and storage conditions for organic materials at the National Museum are largely the result of well-directed human energy and expertise, focused on immediate solutions. Nonetheless, the department of organic materials still lacks the basic conditions for stable storage of these sensitive materials, and we hope that it will be possible to obtain funding for structural improvements, climate control and facilities for isolating and eliminating biological agents. While this department has recourse to the Textiles department facilities for emergency artifact treatment, due to the size and nature of both collections we advocate the development of a separate laboratory for the study and treatment of non-textile organic materials.

The archival data essential for identification and reestablishing context for most materials in this area are the inventories produced on site by Tello's excavation team. Once the basic database of those inventories was complete, a copy was provided to the Organic Materials department and has been incorporated into their ongoing work, both to improve the contextual information available for registered artifacts and to inform the registration of materials being newly incorporated into the department's database.

While the Dumbarton Oaks project as originally proposed has focused on contexts within the Paracas Necropolis cemetery groups, due to the nature of the work in Organic Materials, objects from both Necropolis and Cavernas contexts were processed at the same time. This has provided a set of comparative data useful for building information on patterns of similarity and difference in the artifact assemblages typical of these distinct mortuary complexes.