Introduction

In our research proposal we introduced the site of Ramat Rahel (Jerusalem, Israel), its uniqueness, and the royal garden that was found at the site. A number of research question were presented:

- What was the full extent of the garden and how did it relate to the monumental architecture found above it?

- What is the exact date of the creation of the garden and what is its historical and cultural background?

- What kind of vegetation and which species were planted in the garden?

- How did the water facilities operate and how do they relate to other features in the garden?

In our 2008 season we mainly focused on the first two questions: the extent and the date of the garden. In this interim report we shall first present our field achievements (part of it with the assistance of the grant we received from Dumbarton Oaks), and then our future plans, including some suggestions for future cooperation.

The Results of the 2008 Field Season

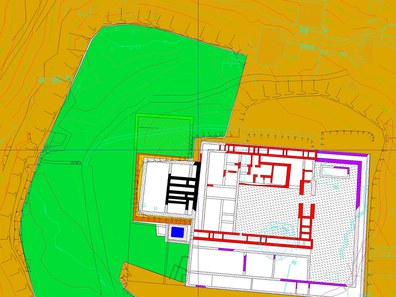

The main features that characterize the garden are known to us from our 2006–2007 field seasons at the southwestern corner of the site (our area C1, see fig. 1). We are familiar with the soil's nature and with the construction work done before the garden soil was laid (i.e., rock-cutting and surface flattening). With this knowledge in our minds we set to the field again for four weeks in an attempt to track the garden's characteristics in new locations.

Our field method included four stages:

- Four trenches were cut in different locations at the site with a mechanical tool. The trenches were ca. 50 meters long and 0.60 meters wide. They allowed us to follow the artificially flat bedrock to the west and to the north. The profile of the trenches also allowed us to check how far the 'garden soil' that topped the flat bedrock extended.

- Exposure of the garden by excavations: following the trenches we opened two new excavation areas: area C4, located to the west of the palatial architecture, and area B2, located to the north of the palace. The aim of the excavations in both areas was to widen the exposure of the garden's strata seen in the sections made by the trenches.

- Following the excavations, in locations where we understood that the garden strata are covered only by modern fill, we removed this fill. This allowed us to visualize and reveal the relationship between the garden and the palatial architecture built on the artificially created summit of the site.

- Since it was realized that the garden occupied the entire western summit, we initiated a survey of the western and southern slopes of the hill in order to map all built terraces and rock-cut agricultural installations (fig. 2). Hypothetically, the terracing of the hill could have been done as part of the garden construction. This survey was done in cooperation with the Israel Antiquities Authority mapping unit.

Our four-stage strategy helped us to answer the first two questions presented above. The plan presented in fig. 3, showing the extent of the garden and its relation to the built palace, is based on our field achievements. Apparently the garden surrounds the palace from three sides. We are still uncertain about the date of the terracing of the hill (see below). We also know now that the garden was built only in the second building stage at the site, dating to the end of the Iron Age period in Israel (7th–6th century BCE), and that some modifications were made during the Persian period.

Future Investigations

In our coming field season we plan to devote considerable effort to the understanding of the garden itself. We wish to examine the soil in order to:

- Identify its source and why it was chosen by the garden planners.

- Identify the plants that grew in the garden.

- Identify fertilizing material and techniques.

These examinations will be done in cooperation with an archaeobotanic and a soil expert. We are still looking for potential partners.

Another line of field research will be to examine the built terraces identified and mapped during the survey. We will continue the detailed survey. We will conduct experimental excavations next to some of the terraces to see if the soil they retain contains clues for the date they were constructed.

In this field of research we wish to cooperate with experts in the Garden and Landscape Studies program at Dumbarton Oaks. We can cooperate with them in our field work in the coming summer, supply large quantities of samples, present our findings in a joint seminar at Tel Aviv University or at Dumbarton Oaks, or in any other way that can be suggested.

I wish to thank Dumbarton Oaks for awarding us a $4,000 grant and wish for further cooperation at this unique site, where the only known garden from biblical-era Palestine can be studied.