Project Summary

The excavations at the Byzantine rural settlement of Kilise Tepe provide new primary data for the changing nature of rural settlement and economy in Isauria between the fourth and thirteenth centuries AD. During the 2009 season, we excavated selected Byzantine buildings located to the east of the church and their associated features, artifacts, and environmental remains.

Introduction

The investigation of the Byzantine levels at Kilise Tepe represents one of the first significant excavations of a Byzantine rural settlement in south-central Anatolia. The location of the mound at Kilise Tepe provides an ideal case study both for rural settlement and for settlement history in Isauria since it lies in an agricultural basin of the strategic Göksu valley that links the Mediterranean to central Anatolia. The archaeological preservation of the Byzantine buildings, although buried close to the surface of the mound, is remarkably good. We are therefore able to investigate the dynamics of this rural settlement by contextualizing relationships at different scales: between the artifacts and features within a room, and between structures within the site. At the same time we are able to consider Kilise Tepe as a case study for the region.

The mound at Kilise Tepe also provides an interesting contrast to the contemporary monumental ecclesiastical site at Alahan excavated by Michael Gough, lying further north in the Göksu valley, and to coastal towns and cities, such as Anemurium, excavated by James Russell, and Elaiussa Sebaste, under excavation by Professor E. Equini Schneider (La Sapienza, Rome). It also complements surveys carried out further north in the valley by the Göksu Archaeological Project, directed by Prof. H. Elton (Trent), and of the limestone settlements close to Silifke, directed by Dr. G. Varinlioğlu (Dumbarton Oaks). Kilise Tepe can be considered both as a subsistence agricultural community and as part of wider economic and social networks in which its inhabitants participated.

We are therefore interested in levels of subsistence and production at Kilise Tepe at particular periods and through time. One of the benefits of excavating earlier periods is it allows us to place the Byzantine phases in the context of long-term changes. The analysis of individual buildings and their position in the wider settlement enables us to account for the activities occurring in social spaces, both in- and outside the houses and in the settlement as a whole. By contextualizing the evidence from artifacts, and by using environmental sampling, we will be able to consider the dynamics of everyday rural life in Byzantine Anatolia in ways rarely attempted before.

The position of Kilise Tepe on the Göksu valley floor makes it an ideal calibrator for settlement dynamics in the region, in particular because of the period of uncertainty, after the Persian and Arab invasions of the seventh to ninth centuries, that followed an earlier stage of perceived growth in settlement density across the eastern provinces. The location of the site inside Byzantine territory, but in a pass protected by the castle at Seleuceia (Silifke) close to the broad frontier zone with the Islamic empire, makes it an important case study.

Project Structure and Economies of Scale

The excavation of the Byzantine levels, directed by Dr. Mark Jackson (Newcastle University), has operated under the umbrella of the larger multi-period KT project directed by Professor J. N. Postgate (Cambridge University) since work recommenced in 2007. Byzantine work was financed in 2007 by the British Academy and in 2008 by Newcastle University.

Previous Work

In 2007, the excavations from 1994–1998 at Kilise Tepe were published (Postgate and Thomas 2007). The focus of the Byzantine work at that time was on the church, and revealed that an early Byzantine basilica was replaced by a medieval church and cemetery dating to the twelfth century. The current program of excavations, from 2007 to 2009, concentrates on the features of the rural settlement around these monumental structures.

Preliminary Results of the 2009 Season

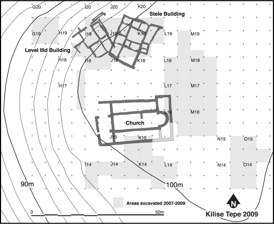

For the Byzantine period, our main aim in 2009 was to consider the role of the church within the wider settlement at Kilise Tepe. We finished work begun in 2008 in K15 on the building to the south of the church, we expanded previous excavations in area N15-O15, and we opened a large trench (in squares M16, M17, L16 and L17) east of the church.

This wide area east of the church enabled us to reveal the layout and orientation of a building of considerable size.

The walls of the building complex lying east of the church were constructed of field stones without mortar. Its west wall ran on a NNW orientation passing 1.0m from the northeast corner of the church. The structure had several large rooms, and it extends to the south and east where it remains unexcavated. Towards the center of the complex was a space with a paved floor, and on the north side a walled, external area where two fire installations were built along the west side of the east wall.

By contrast, our work in N15 and O15 in 2007–2008 seemed to suggest that the buildings in this area had been abandoned, with their contents left lying in situ. This year we extended our excavations from N15-O15 south into N14-O14 in order to establish the southern extent of the large complex of buildings in this area. Here we demonstrated that the complex continues south of wall W4701, excavated in 2007. Our focus here was a room with internal dimensions of 3.60m x 7.00m, and whose floor was at a lower level than the surfaces outside.

Access into the room was by a stone staircase running south from the northwest corner, and also perhaps initially by a doorway in the south wall. A stone bench ran along the north end of the east wall W5200, and an internal partition wall, terminating in a vertical wooden post, divided the northern and southern halves of the room. At the south end of the room several large storage jars were located. On the north side of the partition wall there was a fire installation made of two large stones tipping in toward each other, and closely associated with a plain juglet. In the center of the room was a large circular limestone block 0.62m in diameter with pockmarks in the surface. The room was flagged at the north end, and toward the south the floor was made of tamped earth on which a late Roman Amphora 1 was resting. The layout and finds support several interpretations for this room, which may have formed part of a domestic structure or possibly a workshop.

Conclusions

In 2009, therefore, we provided considerable new evidence for the context of the early Byzantine church, and detailed evidence for particular associated structures which seem to have been abandoned, with finds left in situ. We also confirmed further evidence for the cemetery at the very end of the sequence at Kilise Tepe. Our priorities for the future are to clarify the date of the early Byzantine abandonment and to provide a more comprehensive plan of the Byzantine site as a whole.

Post-Excavation Work

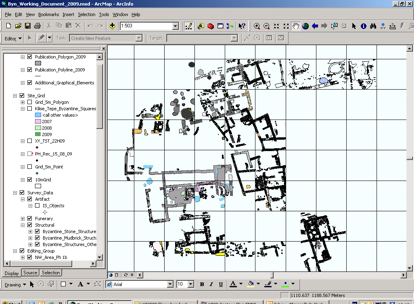

Plans from the 2009 season have been added to those digitized from all previous years. These have been incorporated into a Geographical Information System (GIS) and combined with the data collected since 2007. These data include all plans, 3-D positions of artifacts, geophysical survey data, and aerial photographs. The GIS links to other databases containing information on the small finds, glass, and ceramics, and enables us not only to store the data efficiently but also to explore them more effectively. The GIS was developed by Tim Sandiford.

Future Seasons

Since our season in 2009 radiocarbon analyses have been funded by a grant from NERC-AHRC and work has continued on the post-excavation program. Dr. Jackson is working on the ceramics. Analysis of the squeezes and photographs of the coins has been carried out by Dr. S. Moorhead (British Museum). We plan to conduct a study season July-September 2010 during which we will work on the report from the first three seasons (2007–2009). We will be joined by Dr. M. O’Hea (University of Adelaide) who will work on the glass. This study season will enable us to prepare for our final report and provide a firm foundation for the final excavation season in 2011, which we anticipate will be followed by a shorter final study season.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the British Institute at Ankara. The research was supported generously with funding from Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., and Newcastle University. Dr. Jackson (as co-director for the Byzantine) would like to acknowledge the support of Professor Postgate (Director of the Kilise Tepe Archaeological Project), the assistant director Dr. C. S. Steele, and our Photographer Bob Miller (University of Canberra), who took all photographs. We are grateful to Professor J. Crow, Professor H. Elton, and Dr. M. Mango for acting as reviewers. Dr. D. Collon (British Museum) worked on the small finds, Dr. P. Popkin (BIAA) on the zoo-archaeological material. Trench supervisors, who also helped with much of the ceramics processing were students and postgraduate students of Newcastle University: S. Moore, K. Green, K. Banfield, J. Levell, and T. Hawkins. Our draftsman and surveyor was T. Sandiford (Brown).

Selected Bibliography

Collon, D., M. Jackson and N. Postgate, “Excavations at Kilise Tepe 2008,” Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı, 31 (2010): 159–84.

Postgate, J. N. and D. C. Thomas, eds., Excavations at Kilise Tepe, 1994–98: From Bronze Age to Byzantine in Western Cilicia (London / Ankara: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research / British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, 2007).

Jackson, M., “Medieval Rural Settlement at Kilise Tepe in the Göksu Valley,” in Archaeology of the Countryside in Medieval Anatolia, ed. T. Vorderstrasse and J. J. Roodenberg (Leiden: NINO, 2009), 71–83.

———, “Byzantine Ceramics from the Excavations at Kilise Tepe 2007 and Recent Research on Pottery From Alahan,” Arkeometri Sonuçları Toplantısı 24 (2009).

———, “Local Painted Pottery Trade in Early Byzantine Isauria,” in Byzantine Trade 4th–12th Centuries, ed. M. M. Mango (Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 137–144.

———, “The Kilise Tepe Area in the Byzantine Period,” in Excavations at Kilise Tepe, 1994–98: From Bronze Age to Byzantine in Western Cilicia, ed. J. N. Postgate and D. C. Thomas, 19–30.

———, “Level I Pottery from Kilise Tepe,” in Excavations at Kilise Tepe, 1994–98: From Bronze Age to Byzantine in Western Cilicia, ed. J. N. Postgate and D. C. Thomas, 387–436.

———, “The Byzantine Stratigraphy: The Church, Level I: I-M14”; “Level I: North West Corner”; “Level I: NE Corner Sub Surface,” in Excavations at Kilise Tepe, 1994–98: From Bronze Age to Byzantine in Western Cilicia, ed. J. N. Postgate and D. C. Thomas, 185–211.

Jackson, M. and N. Postgate, “Kilise Tepe 2009,” Anatolian Archaeology 15 (2009): 21–23.

———, “Excavations at Kilise Tepe 2007,” Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı 30 (2009): 207–232.

———, “Kilise Tepe 2008,” Anatolian Archaeology 14 (2008): 23–25.

———, “Kilise Tepe 2007,” Anatolian Archaeology 13 (2008): 28 and cover.