Medieval Paintings in the Levant

The medieval archaeology of the Levant is still far from becoming an important tool in uncovering the history of the region, although considerable progress has been made in this field during the past two decades. From this perspective the fact that wall paintings, as a more spectacular aspect of the culture of that period, attract more attention than architecture or pottery, seems natural and is reflected in the scholarly literature. A significant number of wall paintings discovered or rediscovered in several churches of Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria, and their exceptional state of preservation, make them invaluable witnesses documenting the multi-cultural world of the Levant in the Crusading period. Gustav Kühnel (Kühnel 1988) published a significant study of the monuments from Palestine. Lebanon, an important region on the map of Crusader period art, has also benefited from several noteworthy publications, by Lévon Nordiguian and Jean-Claude Voisin (Nordiguian and Voisin 1998), Mat Immerzeel (Immerzeel 2000; Immerzeel 2009), Nada Hélou (Hélou 1999), and in particular by Erica Cruikshank Dodd, who published a catalogue of murals known from the churches and monasteries of Lebanon (Cruikshank Dodd 2004).

Even if we acknowledge the predominance of studies on medieval iconography, we should be aware of the urgent necessity for a complex and multidisciplinary approach in order to place these monuments in a proper context based on the more profound understanding of the material culture of that period in the Levant. Relatively new publications show that the process has already begun (Ellenblum 1998; Boas 1999).

The project that was completed in 2010, in important part owing to the generous support of the Dumbarton Oaks Project Grant Program, reflects the same perspective. The discovery of the wall paintings in Kaftûn led to the multidisciplinary study of this important monument of 13th-century iconography in close relation to its architecture, benefiting from methods that are still too rarely employed in the medieval archaeology of this region.

Objectives and Anticipated Research Methods

The research program established by our team at the start of work in the church in 2004 focused on the church's architectural history and its wall paintings. More specifically, conservation procedures demanded that we execute numerous probes across the plaster layers inside the church in order to identify those areas where paintings still survived on the walls, uncover the surviving paintings, evaluate their state of preservation, all leading to their consolidation, cleaning, disinfection, impregnation and final aesthetic treatment. The conservation process of the paintings inside the church was completed successfully in August 2009.

The aim of the present project proposed for the academic year 2009/10 was to document the recently discovered and conserved wall paintings in their architectural context, and to gather the graphic material necessary for publication. Data acquired during the project included the photogrammetric images, photographs, drawings, architectural plans, 3-D models, and the results of the archaeological and architectural survey. Research focused also on the technological issues related to the paintings. The duration of the project was limited to 7 months, namely the fieldwork season in July and August 2009 and the elaboration of the results during the following months.

The importance of the forgotten heritage of Christian Lebanon evoked in the title lies in the fact that the material traces of medieval Christianity in the Levant are disappearing irrevocably, and all efforts focused on salvaging this heritage are warmly welcomed by both local communities and scholars.

Mar Sarkis and Bakhos Church in Kaftȗn

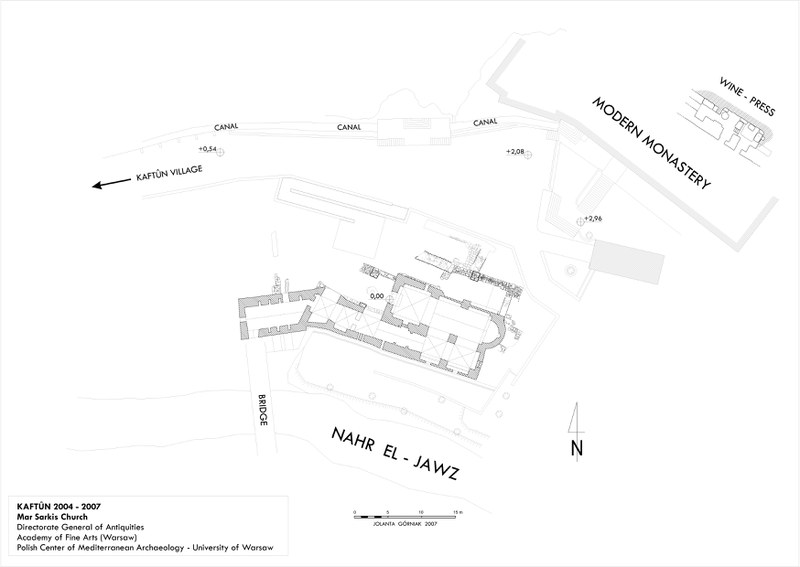

The Greek Orthodox Theotokos Monastery in Kaftûn is situated in the deep valley created by Nahr el Jawz, in the Koura region, below the village of Kaftûn. The monastery draws its name from a Syriac word (KEFTÔ) meaning “arch" or “vault,” and is located under a huge rock that looks like an arch on the shore of the river.

The monastery was mentioned for the first time in 1141 when Daniel, a monk from Kaftûn, was designated to become the abbot and administrator of a monastery in Cyprus called the monastery of Saint John, at Kuzbandû (Kotsovitsi), in the mountains near present-day Nicosia. The sources seem also to distinguish in Kaftûn between an important Maronite monastery dedicated to the two martyr saints Sergius and Bacchus (Mar Sarkis and Bakhos), and a smaller Melkite convent nearby carved in the rock and dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The monastery survived the Mamluk period and remained very important, but during the Ottoman period experienced a slow decay (for the history of the monastery, see Mouawad 2001–02).

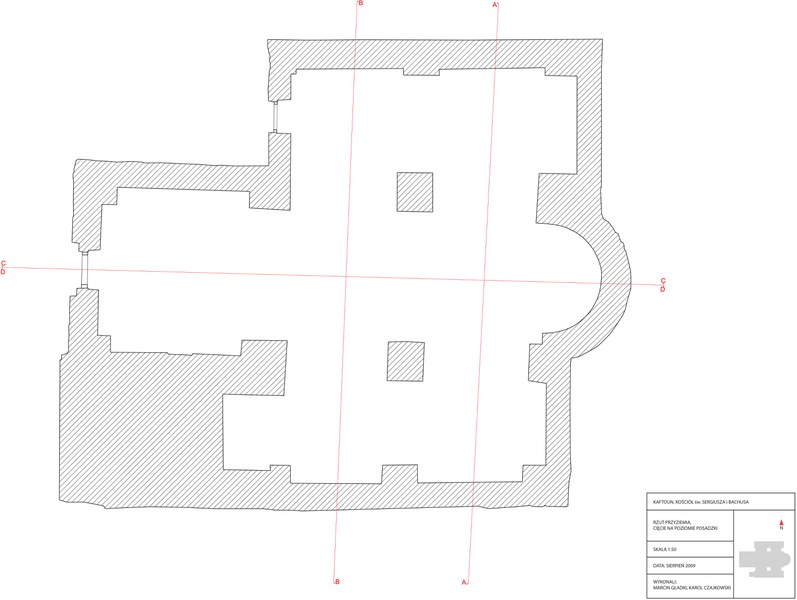

Revitalized by the Archbishopric of Mount Lebanon since 1977, it has revealed an important medieval monument: the Church of Mar Sarkis and Bakhos that stands approximately 30 m southwest of the modern monastery building. The nave (8.42 m long, 4.70 m wide) survives in its entirety together with the apse and south aisle. To the west, inline with the main axis of the nave, are the rooms of the vestibule and a series of rooms aligned with the south aisle. These annexes have a combined length of approximately 17.80 m and an average width of 2.50 m, and terminate in a room that once served as a watermill. The church originally had a central nave with two aisles separated by six pillars on which a series of arches was raised supporting the walls of the nave.

Conservation of Wall Paintings

When it was uncovered in 2004–05, the wall paintings were in a poor state of preservation and in danger of further degradation. Destruction was inflicted not only by the rain water infiltrating the interior of the church and the roots of plants growing on the walls, but also by human activity over the course of centuries. Delaminated layers from the underlying wall surface, weakened mortar, mural surfaces covered in thick layers of salt, gypsum, calcite, and argillaceous contaminants, which obscured many details of the compositions: such were the problems faced by the conservation team.

Emergency measures taken immediately after the discovery has safeguarded all murals and consolidated the delaminated plaster layers. A series of multiple injections was carried out, which introduced an aqueous dispersion of acrylic resins into the shallower areas of delamination between plaster layers and filled the deeper voids with synthetic-resin-modified mineral binders. Also, the edges of any damaged plaster were strengthened by impregnating them with acrylic resin and fitting a strip of fresh lime-sand mortar around them. The surfaces of all uncovered paintings and plaster were disinfected several times, as was the entire church interior. Once the consolidation of the plaster layers was completed, the mural surfaces were cleaned in preparation for their final documentation and limited retouching. Despite the difficulties encountered, most of the paintings were successfully cleaned, making them far more legible—their colors were more intense and shapes more distinct.

Wall Paintings: Their Iconography, Technology, and Chronology

The upper part of the apse, above the cornice, is adorned with a Deesis scene featuring an enthroned Christ making a gesture of blessing with his right hand and holding an open book in his left. The Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist are depicted standing next to him in a pose of supplicative prayer. Theophanic visions are not completely strange to the medieval churches in the region. We found them in the churches of Mar Tadros in Bahdidat, Saïdet Qassouba in Jbeil, Saint George in Rashkida, Mar Demetrios in Kousba and in the chapel Saïdet Naya in Kfar Shleiman.

On the east wall above the arch of the apse is a scene of the Annunciation, featuring the Archangel Gabriel on the left and the Virgin Mary on the right. Mary is clad in a red robe. She holds a spindle in her left hand. Behind Mary part of an arcaded building covered with a red roof can be seen.

The Communion of the Apostles, divided into two sections, is depicted on the side walls of the nave. Christ is shown administering communion to a standing row of apostles on the north and south walls. Both parts of the scene are damaged and incomplete. Usually in the Byzantine art, the Communion of the Apostles is depicted on the apse wall, below the cornice. Apparently at Kaftûn, this place was occupied by the row of bishops.

On the north wall of the nave, below the Communion scene by the apse, is the figure of Saint Lawrence, archdeacon of Rome at the time of pope Sixtus II, clad in a white robe, with an angel blessing him on the left. This place was usually reserved for figures of deacons as in examples from churches at Bahdidat or Deir es Salib in Lebanon or Mar Musa and Mar Elias at Ma’arrat Saydnaya in Syria.

Life-size standing figures feature on the inner arches of the arcades in the walls separating the nave from the side aisles: two saints (patriarchs or prophets?), a figure of Saint Bacchus clad in armor and holding a spear, a figure of an armor-clad Saint Sergius, Saint George, and probably Saint Theodore.

All of the figures and scenes are depicted against a blue background and framed by dark red borders. Fragments of inscriptions survive in several places. These are written in Greek and Syriac (white letters on a blue background), and in Arabic on the cornice of the north wall of the nave (black letters on a white background).

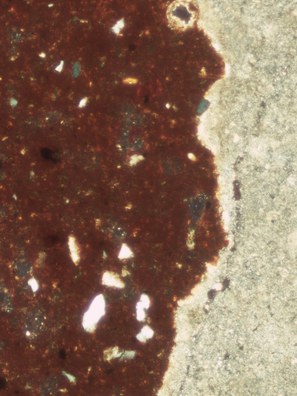

The stratigraphy of the plasterwork sheds some light on the chronology and technology of the murals. In the apse and on the arches of the arcades, they are covered with a layer of pale grey lime mortar containing visible charcoal flecks, or with a layer of dark-brown mortar mixed with clay, which bears impressions made by a flat tool. These mortar layers reduced the curvature of the rounded wall surfaces and evened out the stone substrate. Overlying these coats of mortar is a whitish-cream, lime-and-sand mortar which varies in thickness from several millimeters up to about 2 cm. On the flat walls of the nave this layer was applied directly onto the stone blocks. It is covered by a white layer of lime mortar adorned by a mural, which bears the technical traits of a Byzantine fresco. Brown pigment was applied to wet plaster to make the preliminary sketch of a composition. The first layer of colored ground was probably also applied when the plaster was still wet. Areas of the face were given a dark-green background (known as the proplasmos and characteristic of Byzantine painting technique), shades of ochre were used for robes and dark gray for areas of sky. The fundamental modelling was probably executed using the fresco secco technique, in which pigments are mixed with lime-wash as a binding medium.

The murals represent a high technological and artistic standard, indicating that those who painted them were both technically adept and well-versed in the principles of their art. There are many indications that the Kaftûn murals, preliminarily dated to the second half of the 13th century, were the work of a group whose knowledge and experience were of a higher level than that represented by other known examples of medieval church decoration in the Lebanon.

The fact that all figures were painted on the same layer of plaster speaks in favor of their contemporaneity. There are however noticeable differences between the rendering of the figures in the extant mural fragments on the side walls of the nave (including the Communion of the Apostles and Saint Lawrence) and all others (Annunciation, Deesis, and the saints on the pillars). The first group reveals many traits common to the art that flourished in the second half of the 13th century in Orthodox centers like Serbia or Kosovo beyond the Frankish occupation of Byzantium (1204–61). The second group is more Oriental, local, but always under a heavy Byzantine influence. These observations seem to support the working hypothesis that the church’s decoration was painted by two independent teams of artists working more or less at the same time.

Dumbarton Oaks Project Grant Activities, 2009–10

The 7 months of the project were split into two main phases. First, the fieldwork season took place in Kaftûn in July and August 2009. During that time the members of our team were working on different elements of our program. Their activities are briefly described below. Then, between September 2009 and January 2010, the data acquired were studied. Different team members were working on the photogrammetric modeling of the church and its decoration, illustrations for the publications, laboratory analyses of samples taken from the church, and the analysis of the results of the limited survey of the village.

Study and Documentation Work in the Church

Photogrammetric Measurement of the Church and Its Wall Paintings

The advantage of using photogrammetry in the process of documenting architecture or murals lies in the fact that in a relatively short span of time we can obtain a precise 3-dimensional, scale image of the monument. In Kaftûn the stereophotogrammetry was determined by measurements made in at least two photographic images taken from different positions. Common points were identified on each image. Then the images were orthorectified and dropped on top of the grid. We used the 3D Leica Cyrax 2500 scanner and Topcon Tota Station in the field and Topcon ImageMaster Pro, Photomodeler 5 Pro, and CAD+Raster Design/WiseImage softwares for the post-field treatment of images.

As a result, we have obtained scale, high resolution images of each painting, including details and entire compositions. Likewise, the detailed images of each of the façades of the church and the adjacent annex were made. The acquired data were used to create a 3-D model of the church and its annex, as well as a 3-D model of the interior of the church with its murals. The photogrammetric measurements have also given us a cross section of the church with exact placement of the paintings, and has enabled a proper architectural study of the building.

Architectural History of the Church at Kaftȗn

The proper documentation of the architecture of the church provided the opportunity for a detailed study of its history. The church was constructed using local building materials—limestone and ordinary, unworked fieldstones. The size and working of the stone blocks used in individual sections of the building’s façades varied. In most cases, ashlar blocks were only roughly hewn and not smoothed in any way.

There are two fundamental phases identifiable in the church’s development: before the structural failure and after it. From the very beginning of its existence the church was a three-aisled building, as evidenced by the homogeneity of the lower part of its east wall and by the vestibule preceding the nave. At that time that the nave had a different roof than the one it has at present, probably a flat one. Traces of the original roof structure take the form of vertical wall fragments surviving to a maximum height of 0.68 m on the inside of the nave, above the cornice.

A structural failure caused the collapse of the roof and the north aisle with its annexes. So far, the cause of this accident is unknown. The roof over the nave was lowered and a barrel vault was built that concealed the murals above the apse. The north aisle was not rebuilt until 2007. Owing to construction activity in and around the church prior to our arrival, all archaeological evidence has disappeared. The only credible chronological element is given by wall paintings and their iconography (second half of the 13th century). We can nevertheless assume from the analysis of the walls that the church was constructed earlier.

Analysis of Mortar and Plaster Samples

During the fieldwork season samples of the paintings, pigments, and binding material were taken. Twenty-two of them were analyzed at the laboratory of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. A microscopic and instrumental analysis was employed using the Nikon stereoscopic microscope 100x and Nikon Biological Miscroscope 680x for microchemical and microcrystaloscopic methods. Thin sections were prepared for petrographic analysis of every sample, using Oton petrographic polarizing microscope 480x. Thin sections were viewed under two different lighting conditions-plain polarized light and crossed polarizers. Also, an instrumental analysis—X-Ray difractometry (XRD)—was applied. As examples we present below three samples.

Sample Kaf 22 is a lime and clay mortar that reduced the curvature of the wall surfaces. The binder is composed of calcite and clay when the filler contains mostly particles of quartz, dolomite and magnesite. No traces of gypsum or egg white were found.

Samples Kaf I and Kaf II are composed of two layers: the plaster attached directly to the wall and the surface layer on which the fresco painting was executed directly. In both, the calcite (CaCO3) was used as a binder and lime, clay and ilit as a filler. In both as well, the binder predominates over the filler in terms of quantity, and no traces of gypsum or egg white were found. Ongoing and planned laboratory analysis of the mortar and paint layers will broaden the existing range of observations and technological insights into the less explored aspects of the Crusader-period art in Kaftûn but the proper comprehension of the technological aspects of wall paintings in Lebanon will be made possible only after more samples from neighboring churches have been studied.

Survey of the Ottoman Village

A limited archaeological and architectural survey of the ruined Ottoman-period village was necessary to better comprehend the context of the church but also the extent of the monastery and its economic foundations. The settlement, composed of 6 houses, is situated on the eastern slope of the hill covered now by the agricultural terraces and olive groves, some 600 m west of the Mar Sarkis and Bakhos Church down the river Nahr al Jawz. A water-mill and a church, probably linked to the settlement, are located even further west, near the river.

House 2 is also one-storey but has a basement accessible through the arcades. The basement apparently served as a stable or barn, as evidenced by mangers arranged in the middle. The general dimensions of the building are 14.30 x 14.10 m.

Due to the absence of any comparable architecture from the region, we can only classify them as a typical rural dwellings from the late Ottoman and Mandate period, until recently rarely recorded during the archaeological or ethnographical research in Lebanon. The settlement itself, due to its proximity, should have close ties with the monastery.

Documentation of the Hodogetria Icon from Kaftȗn (11th–13th c.)

A cave chapel that once formed a core of the small Melkite monastery carved in the rock on the opposite site of the Mar Sarkis and Bakchos Church at Kaftûn, and now hidden by the buildings of a modern Greek-Orthodox monastery, shelters one of the most precious Christian documents of Lebanon: a two-sided icon considered the oldest one in the country. One side bears a Hodegetria representation dated to the 11th century. The other side, dated to the 13th century, depicts the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan. Nada Hélou and Mat Immerzeel have shown the similarity between this icon and the newly-discovered murals in the nearby church of Saints Sergios and Bacchos (Hélou 2006; Immerzeel 2007), as well as between some icons preserved in the monastery of Saint Catherine on Sinai that have been discussed by several scholars in the past (K. Weitzmann, L.-A. Hunt, D. Mouriki, J. Folda, A. Weil Carr). The execution of icons from Sinai was attributed to Crusader painters from Southern Italy, a Syriac painter from Cyprus or, according to Jaroslav Folda (Folda 2004), to a "Veneto-Byzantine painter working in Acre." Hélou and Immerzeel propose to consider all these works a product of the local workshop active during the 13th century somewhere in the North Lebanon.

During the fieldwork season at Kaftûn, we have been granted access to the icon by the Greek Orthodox bishop of Mount Lebanon, in order to make a high-resolution photographic documentation of this exceptional piece of art. We also took the opportunity to examine the icon from the point of view of its state of preservation. Some cracks on the surface suggest that the climate inside the chapel should be changed. Basic conservation treatment of the icon was undertaken immediately.

Conclusions

The importance of the project should be understood as an original contribution to the research on the local art of the 13th c. in the Levant, based on the recent and unexpected discovery of the wall paintings in the church at Kaftûn. The material gathered during the project will be included in the preliminary reports as well as a comprehensive final publication about the art and architecture of the Kaftûn monastery. Nevertheless, we should be aware that only a broader study of the wall paintings and their architectural context in the neighboring churches situated in the northern part of Lebanon can change permanently our knowledge about this particular expression of art of the local Christian communities.

This multidisciplinary approach to the problem will, we hope, stimulate further research in the region in setting new standards for fieldwork and the study of the material heritage of the medieval Christian East, particularly in Lebanon.

Acknowledgements

The Kaftûn Project has been financed since 2004 by the National Heritage Foundation (Lebanon), Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts and the Polish Centre of the Mediterranean Archaeology (University of Warsaw). The Dumbarton Oaks grant for 2009/10 was of crucial importance for the pre-publication phase of gathering the documentation that will be processed into a report and a final publication. The project was made possible thanks to our numerous friends. We thank, therefore, the nuns from the Theotokos Monastery in Kaftûn for their support and constant interest in the progress of our work. We thank also Mme Maud Nahas from the Greek-Orthodox Archbishopric of Mount Lebanon for the perfect organisation of our stay. We also recognize our debt towards Prof. Leïla Badre (American University in Beirut), whose idea it was to invite us to Kaftûn. We also thank the Archbishop of Mount Lebanon, Georges Khodr and Frédéric Husseini, the Director General of the Directorate General of Antiquities, as well as Khaled Rifaï (DGA) for facilitating our work on the site. An important role in the project is played by Nada Hélou, Mat Immerzeel, Ray Jabre Mouawad, Lévon Nordiguian, and Wlodzimierz Godlewski. We thank them all.

References

Boas, A. 1999. Crusader Archaeology: The Material Culture of the Latin East. London and New York: Routledge.

Chmielewski, K. and T. Waliszewski. 2005. "Kaftoun - Conservation and Restoration of the Mar Sarkis Church Murals, Interim Report." Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 16:447–52.

Chmielewski, K., T. Waliszewski et al. 2007. "The Church of Mar Sarkis and Bakhos in Kaftûn and its Wall Paintings. Preliminary Report 2003–2007." Bulletin d’Archéologie et d’Architecture Libanaises 11:277–323.

Cruikshank Dodd, E. 2004. Medieval Painting in the Lebanon. Sprachen und Kulturen des christlichen Orients 8. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

Ellenblum, R. 1998. Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Folda, J. 2004. In Byzantium. Faith and Power (1261–1557), edited by H. Evans. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art / New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hélou, N. 1999. "Wall Paintings in Lebanese Churches." In Essays on Christian Art and Culture in the Middle East 2:13–36. Leiden: The Projects Egyptian-Netherlands Cooperation for Coptic Art Preservation, Syrian-Netherlands Cooperation for the Study of Art in Syria.

Hélou, N. and M. Immerzeel. 2006. "A propos d’une école syro-libanaise d’icônes au XIIIe siècle." Eastern Christian Art 3:53–72.

Immerzeel, M. 2000. "Inventory of Lebanese Wall Paintings." In Essays on Christian Art and Culture in the Middle East 3:2–19. Leiden: The Projects Egyptian-Netherlands Cooperation for Coptic Art Preservation, Syrian-Netherlands Cooperation for the Study of Art in Syria.

Immerzeel, M. and N. Hélou. 2007. "Icon Painting in the County of Tripoli of the Thirteenth Century." In Interactions: Artistic Interchange between the Eastern and Western Worlds in the Medieval Period, edited by C. Hourihane, 67–83. Index of Christian Art Occasional Papers 9. Princeton, NJ: Index of Christian Art, Department of Art & Archaeology, Princeton University / University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

Immerzeel, M. 2009. Identity Puzzles. Medieval Christian Art in Syria and Lebanon. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta 184 Leuven and Walpole, MA: Peeters.

Kühnel, G. 1988. Wall Painting in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Frankfurter Forschungen zur Kunst 14. Berlin: Gebr. Mann

Mouawad, R. J. 2001–02. "Les mystérieux monastères de Keftûn au Liban à l’époque médiévale (XII–XIIIe s.): Maronite et/puis melkite?" Tempora, Annales d’Histoire et d’Archéologie 12–13:95–113.

Nordiguian, N. and J. C. Voisin J.C. 1999. Châteaux et églises du Moyen Age au Liban. Beirut: Editions Terre Liban, Editions Trans-Orient.