Transcript

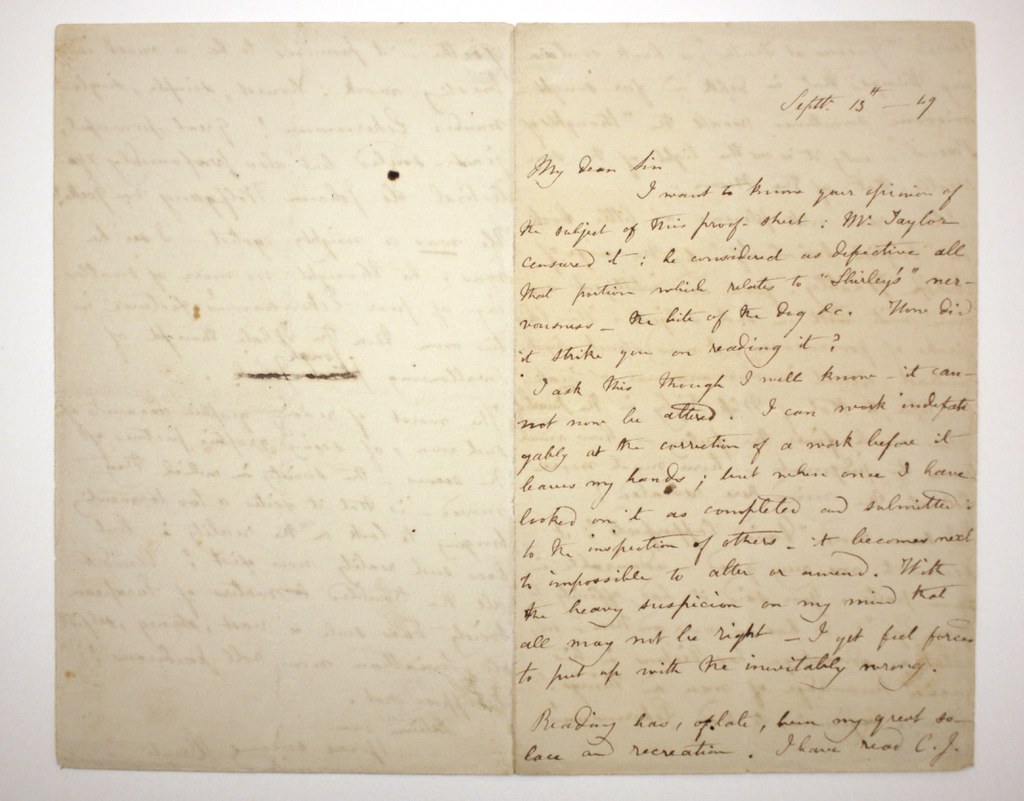

[September 13, 1849]

My Dear Sir,—I want to know your opinion of the subject of this proof-sheet. Mr. Taylor censured it; he considers as defective all that portion which relates to Shirley’s nervousness—the bite of the dog, etc. How did it strike you on reading it?

I ask this though I well know it cannot now be altered. I can work indefatigably at the correction of a work before it leaves my hands, but when once I have looked on it as completed and submitted to the inspection of others, it becomes next to impossible to alter or amend. With the heavy suspicion on my mind that all may not be right, I yet feel forced to put up with the inevitable wrong.

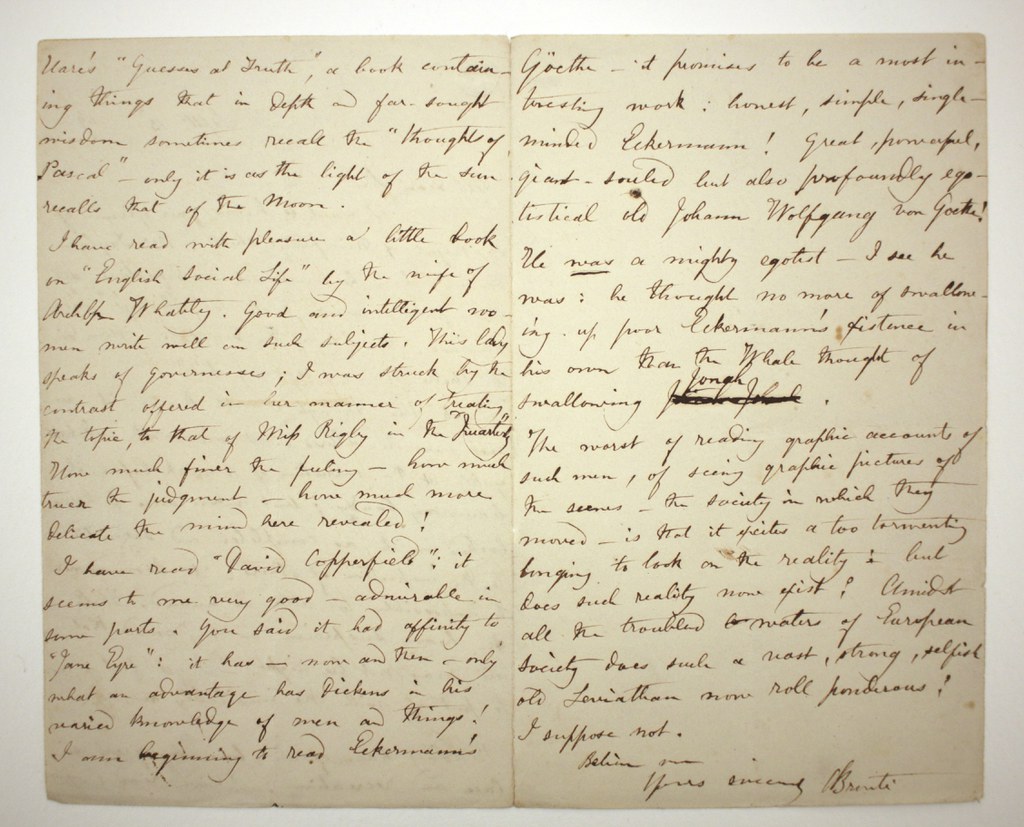

Reading has, of late, been my great solace and recreation. I have read C. J. Hare’s Guesses At Truth, a book containing things that in depth and far-sought wisdom sometimes recall the Thoughts of Pascal, only it is as the light of the sun recalls that of the moon.

I have read with pleasure a little book on English Social Life by the wife of Archbishop Whately. Good and intelligent women write well on such subjects. This lady speaks of governesses. I was struck by the contrast offered in her manner of treating the topic to that of Miss Rigby in the Quarterly. How much finer the feeling—how much truer the feeling—how much more delicate the mind here revealed!

I have read David Copperfield, it seems to me very good—admirable in some parts. You said it had affinity to Jane Eyre. It has, now and then—only what an advantage has Dickens in his varied knowledge of men and things! I am beginning to read Eckermann’s Goethe—it promises to be a most interesting work. Honest, simple, single-minded Eckermann! Great, powerful, giant-souled, but also profoundly egotistical, old Johann Wolfgang von Goethe! He was a mighty egotist—I see he was: he thought no more of swallowing up poor Eckermann’s existence in his own than the whale thought of swallowing Jonah.

The worst of reading graphic accounts of such men, of seeing graphic pictures of the scenes, the society, in which they moved, is that it excites a too tormenting longing to look on the reality. But does such reality now exist? Amidst all the troubled waters of European society does such a vast, strong, selfish, old Leviathan now roll ponderous? I suppose not.—Believe me, yours sincerely, CBronte

Commentary

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, published on October 16, 1847, by the house of Smith, Elder & Co., enjoyed immediate and meteoric popularity. It received praise from reviewers like William Makepeace Thackeray and George Henry Lewes even as it was condemned by a number of lesser periodicals (mostly moralizing scorn that only added to its notoriety). Published under the pen name “Currer Bell,” the novel found remarkable success for a work by a previously unpublished author, going into a third edition by March 1848 and finding an enormous audience in America as well.

Demand for a second novel was high—in many ways, Jane Eyre had been the salvation and the making of its then-tiny publisher—and Charlotte Brontë turned immediately to work on Shirley. James Taylor, one of the office managers of Smith, Elder, came in person to pick up the manuscript of Shirley from Charlotte on September 8; he was on his way back to London after a holiday in Scotland. So Brontë wrote this letter to William Smith Williams, the company reader who had discovered her and Jane Eyre, just five anxious days after Taylor had departed. As is evident in this letter, Williams and Brontë were on close terms, and Brontë had grown to trust in his judgment.

Still, she was cautious and protective of her work, and the firm—following Taylor’s lead—ultimately wanted her to omit a scene where Shirley cauterizes her own arm following a dog bite on the grounds that it was unrealistic. Brontë was piqued by the criticism, since her sister Emily had done exactly that in real life some years before. It had been a hard year for Charlotte: Emily had died on December 19, 1848, and Anne Brontë died on May 28, 1849—both sisters taken by rapid consumption.

This letter is especially notable for the glance it offers at Brontë’s wide-ranging reading habits, and the chatty friendship she had with Williams. Her measured praise for David Copperfield, her interest in the writing of women contemporaries, and her affection for European literature all stand out here—as does her immediate transition from Goethe to a discussion of the bloody aftermath of the revolutions of 1848. Brontë’s reaction is a rather Romantic one—looking for the individual of great genius in the middle of social upheaval, and half-disappointed, half-relieved by the prospect that there is none to be found.