James N. Carder

There’s something mysterious but powerful in that feeling that one has been associated in an enterprise meant to continue long beyond one’s own span of days.

Royall Tyler, June 22, 1938

The period 1934–1940 is unquestionably one of the most important in the chronology of the Bliss-Tyler correspondence, and it is documented by 436 extant letters and telegrams. During this period, the Blisses worked persistently to transform Dumbarton Oaks into a center for research in Byzantine studies, thus increasing their art collecting at a staggering pace. They added over 280 Byzantine and related artworks and 44 non-Byzantine artworks to the collection—a near 140 percent increase in their holdings. The cost of these activities was, in large part, supported by the $12,386,000 estate that Mildred Barnes Bliss inherited when her mother, Anna Barnes Bliss, died in 1935.“12,386,000 Estate Left by Mrs. Bliss; Daughter Is Named Residuary Legatee of Bulk of Patent Medicine Fortune,” New York Times, June 23, 1936. In the same year, Robert Woods Bliss realized a long-held desire to visit Pre-Columbian sites and excavations in Central America, a trip that Mildred Bliss was unable to take due to her mother’s illness and eventual death. Throughout this period, the Tylers, especially Royall Tyler, remained steadfast supporters of the Blisses’ ambitions and advised not only on the acquisition of museum-quality artworks but also on the program and purpose of their embryonic research institute. The prospect of world war, however, became increasingly ominous during this period; it was a major factor in the Blisses’ accelerated pace in building their research center and, indeed, in its transfer to Harvard University in 1940. In 1938–1940, the Blisses engaged the architect Thomas T. Waterman (1900–1951) to construct library and collection pavilions to the west of the Music Room; these were fully installed with books and artworks at the inauguration of the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection on November 1, 1940.

Begin reading letters | Search all letters

The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

Planning for the institutional Dumbarton Oaks had begun already in 1932, when the Blisses somewhat surprisingly traveled to the United States from Argentina to meet with Edward Forbes and Paul Sachs, the directors of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University. They discussed the possibility of creating a research center and fellowship program at Dumbarton Oaks and of leaving the institute to Harvard University at the time of the death of the surviving spouse. On March 10, 1932, Sachs presented a preliminary plan to university president Lawrence Lowell, who received the idea enthusiastically.Paul Sachs to Mildred Barnes Bliss, March 10, 1932; and Paul Sachs to Alfred Gregory, July 19, 1932. History files, Sachs correspondence, Dumbarton Oaks Archives. When Robert Woods Bliss retired from the diplomatic service on April 29, 1933, he began to devote himself, as Mildred Bliss put it, “to the collecting end of the Dumbarton Oaks plan.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to Geoffrey Dodge, January 15, 1937. House Collection files, Dodge correspondence, Dumbarton Oaks Archives. Learning of this “plan,” Royall Tyler was understandably excited and supportive. He wrote Mildred Bliss on June 21, 1934:

Thinking over the collections, public and private, I saw in America, what strikes me most is the general neglect and ignorance of Byzantine. If it were not for the Morgan Coll. and Library, there’d hardly be a first-rate Byz. object, outside of the Oaks. You see what I’m driving at—in fact you knew it all before I started—there’s a huge void in American collections and knowledge, and it’s the whole Byzantine realm. You’ve already done much towards filling it.

After his second visit to Dumbarton Oaks in 1938, at a time when preparations were underway to convert the property into a library and museum, he again wrote Mildred Bliss on June 22, 1938:

It was a great joy to find the Oaks so settled, as compared with four years ago, and so nobly enriched with the things we care for. Seeing them at the Oaks, I’ve again and again had the conviction come over me that I never would have had such a thrill of happiness from them had they come to rest in any other place—even Antigny, for in the nature of things Antigny can’t be hoped to last as the Oaks may last, and there’s something mysterious but powerful in that feeling that one has been associated in an enterprise meant to continue long beyond one’s own span of days.

The Blisses, who had witnessed firsthand the German invasion of Belgium and France during the First World War, became increasingly anxious about the prospect of another world war and the possibility that the Germans would invade the United States. They felt that Harvard University would be better able to protect what they had created at Dumbarton Oaks and, therefore, took the decision to accelerate the date of transfer. As Robert Bliss reminisced in 1945:

As the depression increased and Nazism gained control of Germany we knew war was a certainty and that inevitably this country would be sucked into the cataclysm. So we faced the future squarely and decided to transfer Dumbarton Oaks to the University in 1940. To ease the wrench, we assured each other that freedom of choice is a privilege not often granted by Fate and that to give up our home at our own time to assure the long-range realization of our plan was the way of wisdom. Thus we are enjoying the transformation of Dumbarton Oaks into an institution—the only one of its particular sort in existence.Walter Muir Whitehill, Dumbarton Oaks: The History of a Georgetown House and Garden, 1800–1966 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967), 78.

By mid-January 1939, the new buildings at Dumbarton Oaks were well underway, with the foundations laid and the brick walls under construction. The classical archaeologist Doro Levi, who had recently arrived at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Studies—in large part due to arrangements made by Robert Woods Bliss—was invited to Dumbarton Oaks on January 20 “to spend the week-end and discuss many matters, especially regarding the arrangement of objects in the new room.”Robert Woods Bliss to Royall Tyler, December 7, 1938 (not completed and mailed until January 19, 1939). The French designer Armand Albert Rateau (1882–1938) had designed display cases for the exhibition gallery, his last design project at Dumbarton Oaks.See James Carder, “Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss: A Brief Biography,” in A Home of the Humanities: The Collecting and Patronage of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss, James N. Carder, ed., 15 and fig 1.27 (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2010). See also James Carder, “The Architectural History of Dumbarton Oaks and the Contribution of Armand Albert Rateau,” in A Home of the Humanities, The Collecting and Patronage of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss, ed. James N. Carder (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010), 93–115. The official inauguration of the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection occurred on November 1, 1940, and was attended by Harvard administrators, scholars, and friends.Bulletin of the Fogg Art Museum 9, no. 4 (March 1941): 63–90. The Tylers, however, were unable to attend due to the war. Elisina Tyler was at Antigny protecting the château from looting by the Germans who inhabited the house. Royall Tyler was in Switzerland working with the League of Nations on the war situation. He wistfully wrote Mildred Bliss on November 29, 1940: “I had the invitation to the inauguration of the New Buildings. Alas, that I couldn’t be there. It gave my heart strings a pull to see the Emperor roundelBZ.1937.23. reproduced in it. I liked the look of it. Love to you and Robert, and à bientôt, I hope—”

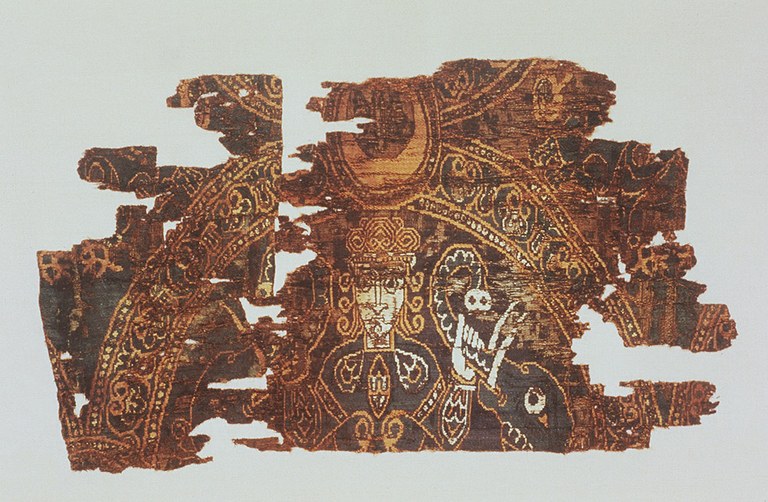

Collecting

During this critical period, Royall Tyler was especially instrumental, as had long been the case, in assisting the Blisses in their acquisition of artworks of high quality. This was a pleasure he took as a relief from the stresses of his work at the League of Nations as the Financial Committee’s adviser to the Hungarian government in Budapest (1931–1938) and as the league’s expert in the Economic and Financial Section (1938–1943). As he wrote to Robert Bliss: “Don’t think it was an imposition . . . . I love doing it—& I won’t pretend I don’t love doing it for its own sake, as well as yours.”Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, September 13, 1934. Bliss acknowledged his indebtedness to Tyler in a letter of May 22, 1937: “But, I do want you to know how keenly appreciative Mildred and I are of all the trouble you continue to take in helping us add to the collection.” Among the important finds Tyler brought to their attention during this period were a textile that he named the “Lion tamer silk”BZ.1934.1. (1934), an ivory diptych of Philoxenus (the “Trivulzio diptych”)BZ.1935.4.a–b. (1935), and an enameled cross reliquary (the “Burns” or “Drey cross”)BZ.1936.20. (1936). Tyler worked particularly diligently to convince the Blisses to acquire a Middle Byzantine ivory representing the Virgin Hodegetria, Saint John the Baptist, and Saint Basil (the “Landau ivory”),BZ.1939.8. the authenticity of which had been seriously doubted by the French art authority Jean-Jacques Marquet de Vasselot. Tyler, believing fully in the ivory’s genuineness and recognizing its high quality, used Marquet’s doubts to gain for the Blisses a substantial reduction in the purchase price. As Tyler put it:

Only I’ll go into decline if you don’t get that ivory. Especially as doubt has been cast on it. I suggested in my wire, to Robert, that he use (without mentioning names, of course) the lack of agreement on it in bargaining. He can truthfully say that some important judges in US don’t think it is Byz.—and LandauNicolas Landau (1887–1979), an antiquities dealer known as “Le prince des antiquaires.” Born in Varsovia, he studied law in Paris before becoming an antiquities dealer in New York and then in Paris, where he had a business on the rue de Duras. knows of Marquet’s rejection. It’s really a god-given piece of luck to have had it doubted, and puts you in a wonderful bargaining position. !Que lo aproveches!“Take advantage of it!” I hope Robert may be able to get it for a fraction of what was asked—but get it he must.Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, November 18, 1938.

Tyler also helped Robert Bliss build his Pre-Columbian collection by acquiring several artworks from the collection of Mrs. Jean Holland that were auctioned at Sotheby’s in London on June 9, 1937.PC.B.045, PC.B.056, PC.B.100, PC.B.101, PC.B.110, PC.B.160, PC.B.161, PC.B.162, and PC.B.249. See Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, June 9, 1937 [1].

Both Royall Tyler and the Blisses realized that the unique conditions of the 1930s had brought about an unparalleled opportunity to acquire truly exemplary artworks. The Great Depression and the rise of Nazism had created instability in the marketplace and brought about the sale of artworks that might otherwise never have changed hands. Although the Blisses never willingly or knowingly acquired art that had been confiscated by the Nazis or Fascists, they did profit both from the economic need of private collectors to sell from their collections and from the Nazis’ disinterest in the art of non-Germanic cultures held in state institutions. For example, they acquired a Persian silk textileBZ.1937.25. from the Düsseldorf Stadtmuseum, “which is also liquidating its ‘Non Aryan’ stuff,” as Royall Tyler explained.Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, September 4, 1937. “Not dear at £35. If you want it, please tell Bill to secure it. Burg-Drey,A collaboration of the art dealers Dr. Hermann Burg and Franz A. Drey, London. now associated, in London, are helping FritzRoyall Tyler’s slang for “Germans.” to get rid of this sort of degraded non-Germanic so-called art.”

Given that German museums were beginning to sell their artworks—a trend that could potentially be followed by church treasuries—Tyler quickly drew up a desiderata list for the Blisses. He wrote Mildred Bliss: “FritzRoyall Tyler’s slang for “Germans.” is willing to sell Byz. things at present. In your place, I’d buy as many first rate Byz. things from him as I could, even paying big prices for them.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, September 4, 1937. His recommendations of what to buy included the very best Byzantine artworks that could, conceivably, be acquired, although, in fact, the Blisses would be mostly unsuccessful in this endeavor. The Blisses realized that they needed to conserve their money and not spend it on lesser acquisitions in the hope that really important objects would be offered up for sale at a price they could afford. Robert Bliss articulated this conundrum in a letter to Royall Tyler of September 25, 1934: “Both Mildred and I feel, however, that it is better to reserve ourselves for something of greater importance that may possibly appear in the market as the times grow worse throughout the world—though there is always the fear, that as time goes on we may not have the wherewithal to purchase anything.” When the dealer Stora offered the Blisses a Hispano-Moresque “Alhambra” vase, Bliss felt that this was not “an object for us. In the first place, it costs a considerable sum, which I would rather put into a purely Byzantine object of a like quality and rarity.”Robert Woods Bliss to Royall Tyler, October 11, 1937 [2]. Tyler agreed completely, writing: “Robert, I beg you to keep your powder-flash supplied, & not to waste any, taking shots at such small game. I really think some of the above marvels may soon come along, and. . . . I won’t waste words.”Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, December 20, 1938.

Among the “marvels” that might come along, Tyler cited the so-called Goldene Tafel, a Byzantine gold and enamel Crucifixion icon that was in the Reiche Kapelle of the Schloss Nymphenburg in Munich. As it turned out, it was actually the property of the House of Wittelsbach,The House of Wittelsbach, a German royal family from Bavaria. Members of the family served as dukes, electors, and kings of Bavaria (1180–1918), counts palatine of the Rhine (1214–1803 and 1816–1918), margraves of Brandenburg (1323–1373), counts of Holland, Hainaut, and Zeeland (1345–1432), elector-archbishops of Cologne (1583–1761), dukes of Jülich and Berg (1614–1794/1806), kings of Sweden (1441–1448 and 1654–1720), and dukes of Bremen-Verden (1654–1719). The family also provided two holy Roman emperors (1328 and 1742), one king of the Romans (1400), two anti-kings of Bohemia (1619 and 1742), one king of Hungary (1305), one king of Denmark and Norway (1440), and a king of Greece (1832–1862). which therefore had a right to sell it. The asking price was reportedly $70,000.Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, September 25, 1934 [1]. In making this recommendation, however, Tyler confessed: “I must add that, as a work of art, it does not greatly appeal to me. I know many smaller enamels that I consider much better. Personally, I would rather possess the BurnsWalter Spencer Morgan Burns (1891–1929), a British art collector and financier, was a nephew of J. Pierpont Morgan and a partner in his firm, J. P. Morgan and Co., as of December 31, 1897. CrossBZ.1936.20. At this time, the reliquary cross was owned by Ruth Evelyn Cavendish-Bentinck Burns, the widow of Walter Spencer Morgan Burns,. which I fancy could be bought for about one fifth of the price asked for the Goldene Tafel. However, the Goldene Tafel is such a morsel that I thought I had better tell you about it.” Not unexpectedly, the Blisses acquired the Burns enamel Crucifixion reliquary. Also, because the Blisses had been successful in acquiring the Philoxenus consular diptych,BZ.1935.4.a–b. which had come from the famed TrivulzioLuigi Alberico Trivulzio (1868–1938), Prince of Musocco and Marchese of Sesto Ulteriano. Trivulzio was responsible for the sale of much of his family’s art collection. collection in Milan, Tyler immediately added other Trivulzio treasures to his list. He wrote: “if Trivulzio is starting to sell, I think you may wish to reserve yourself for that magnificent Xe cent. Christ ivory,Christ Enthroned, Byzantine, second half of the tenth century, ivory, private collection, Switzerland. See Anthony Cutler, The Hand of the Master: Craftsmanship, Ivory, and Society in Byzantium (Ninth–Eleventh Centuries) (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 45, ills. 46 and 47. which is one of the very finest Byz. things known. It will be a big morsel & how Trivulzio will get it out of Italy I don’t know, but he may try.”Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, September 5, 1934. He later added that if things continued to come from “that quarter,” there is another sublime ivory there, the Annunciation,Annunciation, late seventh–early eighth century (?),ivory, Civiche Raccolte d’Arte Applicata, Castello Sforzesco, Milan, inv. A.14. It was acquired from the Trivulzio Collection in 1935. The ivory has been variously dated. See Kurt Weitzmann, ed., Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979), 198–99, no. 448; and Serena Ensoli and Eugenio La Rocca, Aurea Roma: Dalla città pagana alla città cristiana (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2000), 590, no. 284. See also Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition Seventh–Ninth Century, ed. Helen C. Evans with Brandie Ratliff (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), 46–47, no. 24H. “which seems to belong to the Grado throne group.The so-called Grado Chair, a lithurgical throne given by Emperor Heraclius (reigned 610–614) to Grado, Italy, after his successful reconquest of Egypt. The chair was ornamented with carved ivory plaques. See Kurt Weitzmann, The Ivories of the So-Called Grado Chair (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, 1972); and Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition Seventh–Ninth Century, ed. Helen C. Evans with Brandie Ratliff (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), 45–50, no. 24A–N. If either of those two ever fetched loose . . .”Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, October 16, 1934. Even a half year later, Tyler was still hopeful: “The idea of your possessing the Trivulzio Annunciation excites me as much as it could if something had fetched loose out of the Cabinet des Médailles.”Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, March 9, 1935. In 1935, however, the city of Milan acquired much of the Trivulzio collection for the Civiche Raccolte d’Arte Applicata, Castello Sforzesco.

Royall Tyler also recommended that the Blisses attempt to acquire the reliquary of the True Cross (Staurotheke) in the Cathedral Museum at Limburg an der Lahn.Reliquary of the True Cross (Staurotheke), Byzantine, ca. 960, gold, gems, and enamel, Cathedral Museum, Limburg an der Lahn. He further advised trying for a lion silk in the Saint Heribert Diocesan Museum at Cologne-Deutz.Lion Silk, Byzantine, late tenth–early eleventh century, Saint Heribert Diocesan Museum, Cologne-Deutz. The twelfth-century shrine of Saint Heribert, archbishop of Cologne (d. 1021), at Saint Heribert, Cologne-Deutz, has an imperial Byzantine lion silk with an inscription suggesting a date of ca. 976–1025 for the textile. See Michael Brandt and Arne Eggebrecht, Bernward von Hildesheim und das Zeitalter der Ottonen, vol. 2 (Hildesheim, 1993), no. II-19. Most important to Tyler, however, were four Byzantine ivories.See German ivories. One of them, the diptych leaf representing a jeweled cross with the bust of Christ, was in the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein in the Schlossmuseum at Gotha and was of particular interest because the Blisses had acquired its pendant.BZ.1937.18. The other three ivories were the left diptych panel with the Crucifixion and the Deposition in the August Kestner Museum, Hannover; its pendant, the right diptych panel with Christ meeting the Marys in the garden and the Descent into Hell in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Grünes Gewölbe, Dresden; and an ivory panel representing John the Evangelist and Saint Paul in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Grünes Gewölbe, Dresden.

Fritz Volbach, the “Roman friend”

The Blisses were greatly enthusiastic about the possibility of these acquisitions. To insure that negotiations were handled as quietly and discreetly as possible, the Blisses and Tyler decided to entrust Wolfgang Friedrich “Fritz” Volbach, a medieval art historian who had worked at the Vatican Museums, with making contact with the Germans. Volbach, in turn, eventually entrusted much of the negotiating to a retired Swiss banker, Hermann Fiedler. To maintain the highest level of secrecy and discretion in these dealings, Fiedler is often referred to simply with the initial F and Volbach is referred to as the “Roman friend” in the Bliss-Tyler correspondence. In a letter to Robert Bliss of January 7, 1937, Royall Tyler wrote: “If you will authorize me to do so, I’ll talk to the Roman friend—for he knows the collections & the officials well, and we might thus manage to make some interesting acquisitions without paying as heavy a rake-off as has to be paid to dealers. Please let me know immediately whether this last suggestion meets with your approval.” Going on the assumption that the Blisses were not interested in anything except objects of the very highest quality, Tyler instructed Volbach to have a try for the Dresden and Hannover ivories, for a Sasanian textile in the Schlossmuseum in BerlinSee Otto von Falke, Decorative Silks (New York: W. Helburn, 1922), 5; and Hayford Peirce and Royall Tyler, “The Prague Rider-Silk and the Persian-Byzantine Problem,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 68, no. 398 (May 1936): 214, 219, fig. 3A. representing King Bahram of Persia hunting lions, and for the lion silk at Cologne-Deutz. Tyler advised the Blisses:

These four objects are the finest Byzantine works of art in German State possession known to me, and our Roman friend, to whom I mentioned them agrees. If you feel the same way about them, after considering the photographs, you might think it worth while to empower the Roman friend to negociate, after having agreed a maximum price with him, in the determination of which I would of course be glad to help if you wish me to do so.

The Blisses would not succeed in acquiring these objects, as detailed at length in the correspondence. But using Volbach and Fiedler as agents, they would succeed in acquiring two important Byzantine sculptures that belonged to Prince Leopold of Prussia, who was living on Lake Lugano in Switzerland, having moved there from his family home, the Schloss Glienicke, in Berlin-Potsdam. One of the sculptures was a roundel,BZ.1937.23. representing an emperor. The other depicted the standing Virgin.BZ.1938.62.

The Collection

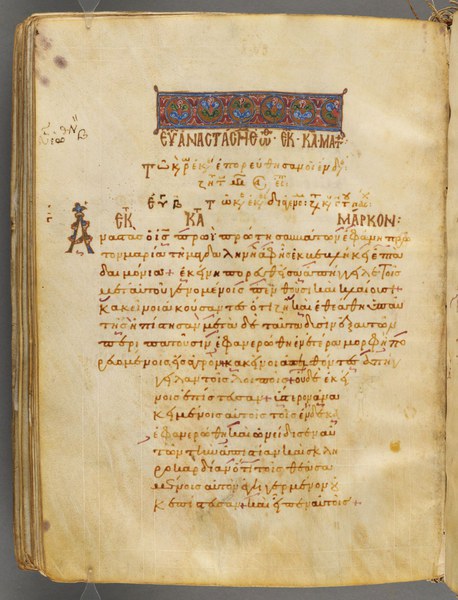

The Blisses realized that their collection was deficient in significant examples of Byzantine illuminated manuscripts and coins, or, as Robert Bliss stated, “we are totally lacking in anything to represent the field of Mss. and coins, both of which are important to round out the collection.”Robert Woods Bliss to Royall Tyler, August 18, 1937. Tyler immediately took up the challenge: “As for MSS, I have some ideas, connected with Mt. Athos. There just aren’t any on the market. We’ll see if the HippiatricaHippiatrica, Byzantine, mid-tenth century, Staatsbibliothek, Berlin, Codex Phillips 1538. . . . . (!!). Coins, I also have some ideas, which we’ll talk over when we meet.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, September 4, 1937. Tyler suggested considering Thomas Whittemore’s coin collection, which eventually went to the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, and Hayford Peirce’s extraordinary coin collection, which Dumbarton Oaks would acquire in 1948. Referring to the latter, Tyler concluded: “Well, we’ll have to talk it over. I’ve never breathed a word to him, but I’ve often thought we might make an effort to secure that for the Oaks. It’s a grand collection, with many unica in it, and hardly any important gaps.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, September 4, 1937. The Blisses tentatively ventured into manuscript collecting by acquiring a Middle Byzantine Gospel Lectionary at a 1939 auction at Sotheby’s in New York.BZ.1939.12.

Despite the Blisses’ focus in this period on the creation of a research institution dedicated to Byzantine studies and art, they nevertheless continued to acquire non-Byzantine artworks of high quality that were to be included in the gift of Dumbarton Oaks to Harvard University in 1940. This was due to the fact that the Blisses wanted Dumbarton Oaks to be what Mildred Bliss called a “Home of the Humanities,”Mildred Bliss used this phrase and its variations in her correspondence; see Mildred Barnes Bliss to John S. Thacher, May 27, 1941, Administration files, Thacher correspondence, Dumbarton Oaks Archives. But she used it most famously in the preamble to her last will and testament, signed August 31, 1966. Blissiana files, Mildred Barnes Bliss, Last will and testament. where all of its components—the estate, the gardens, the interior spaces, and the artworks—were to contribute to the importance of the institution. Among the significant non-Byzantine artworks that the Blisses acquired in this period were paintings by Georges Seurat (1935),HC.P.1935.16.(O). El Greco (1936),HC.P.1936.18.(O). Édouard Vuillard (1936),HC.P.1936.40.(O). and Bernardo Daddi (1936);HC.P.1936.57.(T). a drawing by Claude Lorrain (1936),HC.D.1936.48.(I). a sculpture by Tilman Riemenschneider (1937),HC.S.1937.006.(W). an oil study by Edgar Degas (1937),HC.P.1937.12.(E). an ancient Egyptian Middle Kingdom sculpture (1937),HC.S.1937.011.(W). a painting by Georges Rouault (1938),HC.P.1938.94.(O). and a Romano-Arabian bronze horse (1938).BZ.1938.12. Understandably, Royall Tyler was unhappy with the Blisses’ deviation from the straight-and-narrow collecting of Byzantine art. When Mildred Bliss sent him a list of artworks they hoped to acquire, he responded on September 4, 1937:

Precious Mildred, I’m apalled [sic] by your list of things to be acquired. A bit reassured when you told me you didn’t want to scatter too much, and that Byz. remains the main thing. But I do beg you to consider that if you go in for all you mention in that list you’ll be in grave danger of scattering, and of getting a lot of things of no relevancy to your central subject—and perhaps even not of first quality.

Robert Bliss responded to Tyler on December 31, 1937:

In truth, as you know full well, both Mildred and I are entirely of your opinion that we should keep to our Byzantine field and its allied arts, but, also agreeing with you, there are occasions when one falls from grace! We have been tempted by two objects. You may have seen one which BykPaul M. Byk (1887–1946), an employee of Arnold Seligmann, Rey & Co., New York. has brought over—a most unusual Gothic wooden Madonna seated;This sculpture has not been identified. a really very fine and unusual object. But we have resisted this one. The other is a Sassanian bronze horse,BZ.1938.12. unlike anything I have ever seen before. Of course, Brummer has it! It is fully three feet long, from rump to nostril. We are trying to resist it, and hope we shall succeed, but I do not know.

In acquiring artworks in this period, the Blisses often received adventitious pricing due to the economic conditions of the Depression. For example, in their negotiations with the New York dealer Dikran Kelekian for the Degas drawing and the Egyptian Middle Kingdom sculpture, the Blisses were able to reduce the combined price from $37,500 in 1936 to $20,000 when they acquired the pieces on April 9, 1937. On that date Kelekian wrote to Robert Bliss:

I am glad that you acquired these two exceptional pieces. I sold them to you at your price for three reasons: first, because you and Mrs. Bliss liked them and I wanted to please you; second, I wanted to have the pride of seeing two other most important objects added to your collection containing already several other first class objects purchased from me; and third, I wanted to hurt myself by making a sacrifice on the price so that I should remember the hardship caused to me by relatives towards whom I had been generous.Kelekian was at the time involved in litigation with his nephew. However, I am a good sport and can stand losses. My only wish is that, since you have such good taste and knowledge, you should not pay attention to the advice of ambulant, so-called experts who are far from being disinterested!House Collection files, Dikran Kelekian correspondence, Dumbarton Oaks Archives.

The “ambulant, so-called expert” that Kelekian had in mind was likely Royall Tyler. Tyler previously had cautioned the Blisses against acquiring an expensive molded cobalt glass ewer that was in the Kelekian collection. Moreover, Tyler was aware of Kelekian’s influence over the Blisses. On June 24, 1938, Tyler wrote Mildred Bliss:

Kelek is disgusted with me for having crabbed his RouaultHC.P.1938.04.(O). to you—and I think he suspects me of having instigated Robert to screw him down on the little ivory portraitProbably BZ.1938.63, an ivory statuette of the seated Ares, which Tyler compared to their mutual friend, Hayford Peirce. of Hayford at the ring-side. He little knows how I bullied you to get it—not good for him to know it.

But Royall Tyler understood, perhaps better than anyone else at the time, that the Blisses were first and foremost impassioned collectors. When they wrote him of their interest in a Romano-Egyptian glazed ceramic vaseBZ.1939.31. that they had long wanted to acquire from Kelekian, he wrote back half-heartedly: “I grieve that you should be lured by the old Egypt. thing—but I know what it feels like, and who am I . . . ”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, November 18, 1938.

World Events

Highly significant to the activities of the Blisses and Tylers in this time period were the serious, even catastrophic events taking place in the world. Foremost among these were the rise of Nazism and Fascism and the outbreak of war in 1939, the likely cause of the Blisses’ decision to transfer Dumbarton Oaks to Harvard University in 1940, as discussed above. Curiously, although expecting the worst, the Blisses and the Tylers were, at times, cautiously optimistic that the situation would not escalate into a world war. On April 15, 1939, only five months before the outbreak of war, Royall Tyler wrote Robert Bliss:

What can I say about the internat. situation? It certainly looks much nearer a crash than it has been since the last world war. I may be mad, however, but I’m still inclined to think the crash may not take place. A quick decision, in the event of war, isn’t likely, and without a quick decision the totalitarian states are almost certain to be beaten. I don’t think the German soldier wants to risk it (twice in 25 years—des Guten zu viel“Too much of a good thing.”), nor the Italian. How the crisis is going to develop, Heaven knows: perhaps in some way that may astounish [sic] us all.

The Blisses also were deeply concerned for their Jewish friends, and would continue to inquire after their well being until the war’s end in 1945. The Blisses helped Doro Levi leave Italy in 1939 to become a member of the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton. They also anxiously inquired about the Jewish-German art historian Adolph Goldschmidt (whom they had nicknamed “Gogo”) and about Fritz Volbach. They were even worried about the American Bernard Berenson, who was universally nicknamed “BB” and who lived in the Villa I Tatti near Florence. In a telegram to Royall Tyler on November 15, 1938, Robert Bliss wrote:

What news Gogo? What status Volbach? Avoiding post and telegraph. Convey Doro six months invitation lecture universities bringing wife for work Dumbarton. If without funds advance necessary for journey. If affidavit or university papers required cable me naming consulate having jurisdiction. Also convey BeeBee suggestion he transfer TattiVilla I Tatti, the home of Mary and Bernard Berenson near Florence. As early as 1915, Berenson expressed his intention to leave his house and library to Harvard University, and this intention was reaffirmed in 1937. Harvard only formally accepted the bequest at the time of Berenson’s death in 1959. to University now making financial arrangements later.

Also of deep concern in the Bliss-Tyler correspondence were the deteriorating conditions in Soviet Russia, the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), and what they perceived as the threat of the rise of Communism in the Western world. Tyler, who had traveled in Russia, the Ukraine, and Estonia in August 1935 and who had written the Blisses a long and impassioned narrative of his experience of Russia, its people, and, not surprisingly, its art,Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, August 1, 1935. wrote a year later a strictly political appraisal:Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, September 8, 1936.

Stalin now stands out as an Oriental conqueror-tyrant on the Genghis-Khan pattern,Genghis Khan (1162?–1227), the founder and emperor of the Mongol Empire. After founding the Mongol Empire and being proclaimed “Genghis Khan,” he initiated invasions that resulted in the conquest of most of Eurasia. These campaigns were often accompanied by wholesale massacres of the civilian populations. and the mechanism he is building up in Russia has only a formal resemblance to Lenin’s Communistic State. In practice, it is much more like Old Zarist Russia, with its bureaucratization of every branch of life (even actors & dancers are State officials, distributed neatly along a cut-&-dried scale of rank & payment.) If this tendency is destined to prevail in Russia, & all present signs point that way, the effect on Communism in France & elsewhere may be enormous. The doctrinaire Communist can hardly go on looking to Russia for guidance, Russia may shortly again figure as the ideal of the reactionary, and in this capacity rival Nazi Germany. Then what?

In the same letter of September 8, 1936, he then turned to the Spanish Civil War: “It hurts to think of Spain. Whichever side wins, the prospect is a dark one. The ‘Government’ seems to be sliding into the hands of the Communists, and perhaps even of the Syndicatists (Anarchists).”

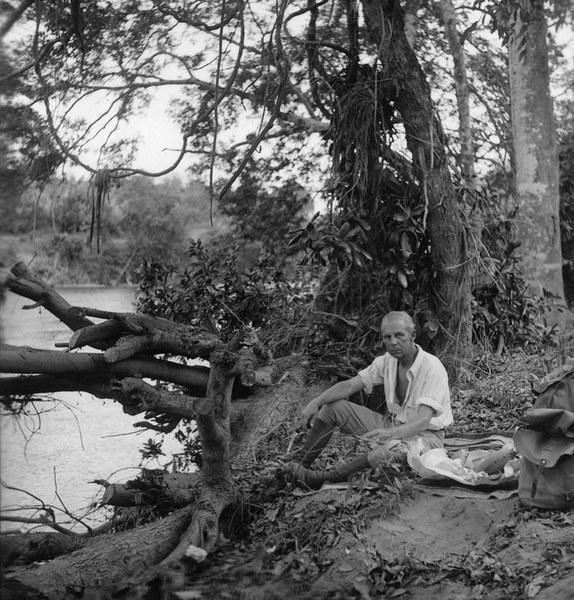

Travels

Despite the deteriorating conditions throughout the world, both the Blisses and the Tylers made several lengthy trips between 1934 and 1940. Elisina and Royall Tyler each visited Dumbarton Oaks for the first time, although they did so separately. Royall Tyler visited twice in 1934 and in 1938, on both occasions in the months of May and June. Tyler had not been in America since 1904. Elisina Tyler also visited Dumbarton Oaks twice during this period, in October–November 1935 and in January 1938. In February–March 1935, Robert Woods Bliss journeyed to the Pre-Columbian sites of the highlands and tropics of Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. Bliss was accompanied by Frederic C. Walcott, a former senator and a trustee of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, D.C. On January 19, 1935, he wrote Royall Tyler:

Our Central American trip is all set. We were to have left today but the pressure here was so great that we have to postpone it for a week. We, (that is, ex-Senator Fred WalcottFrederic Collin Walcott (1869–1949), a U.S. senator from Connecticut (1929–1935). He also served as regent of the Smithsonian Institution from 1941 to 1948. At the time of the 1935 trip, Walcott was a trustee of the Carnegie Institution for Science of Washington, and it was he who made arrangements for the trip. besides Mildred and me) will go first to Yucatan, where we will join KidderAlfred Vincent Kidder (1885–1963), an American archaeologist and specialist of southwestern United States and Mesoamerican archaeology. Many of his excavations were sponsored by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University. of the Peabody Museum,The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, a Harvard University museum founded in 1866, is one of the oldest and largest museums focusing on anthropological material, with particularly strengths in New World ethnography and archaeology. who will be with our Santa Barbara friends, North DuaneWilliam North Duane (1869–1944), a supporter of several archaeological expeditions of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. and his wife,Ethel Phelps Duane (1875–1942). and we shall see that region as thoroughly as possible, staying part of the time with MorleySylvanus Griswold Morley(1883–1948), an American archaeologist, epigrapher, and Mayanist who was noted for the extensive excavations of the Maya site of Chichen Itza that he directed on behalf of the Carnegie Institution for Science. so that I think we will make our visit there under the best possible auspices. Thence, we shall go to Guatemala and see as much of that region as possible before returning. We expect to be here about the first of April.For an outline and images of this trip, see http://museum.doaks.org/IT_1144?sid=795&x=4369&x=4370 (accessed May 21, 2015).

Mildred Barnes Bliss, however, was not able to take this trip due to the illness and death of her mother, Anna Barnes Bliss, who died on February 22, 1935.

The other important trip of this period was the Blisses’ travels in western and eastern Europe between November 1935 and April 1936. The Blisses intended to visit friends in France, Sweden, and Italy; travel for the first time to Russia; and visit the Tylers in Budapest.Their complete itinerary was given in a letter from Robert Woods Bliss to Royall Tyler, January 28, 1936: “Leave Paris Monday evening, February 3rd, arriving Stockholm morning February 5th; leave there Saturday afternoon, 8th; arriving Leningrad Monday 10th, Moscow 14th, Berlin 18th (Esplanade Hotel), Prague morning 21st and leave there night of 22nd, arriving Budapest 7.57 A.M. Sunday 23rd. We propose to stay there until sometime Tuesday so as to have, if possible, a day and a half in Vienna.” In Russia, they intended to examine Byzantine manuscripts in the state libraries, most likely with the hope that the Soviet government might offer some of them for sale in a manner similar to the Soviet sale of paintings from the Hermitage collection in 1930 and 1931. Royall Tyler prepared an extensive list of recommended illuminated manuscripts, making the marginal notation “Get!” for a Menologion in the State Historical Museum in Moscow, Gr. 183:

Get! No. СИНОД. ΓРЕЧ. 183. A very fine Menologion (Martyrdoms). Gory scenes like those in the famous Basil II Menologion in the Vatican,Menologion of Basil II, Vaticanus graecus 1613, an eleventh-century illuminated Byzantine manuscript with 430 miniatures in the Vatican library. and of at least as fine quality. Finer than the Walters (Balt.) Menologion.The “Imperial” Menologion (W.521), Walters Art Museum, an eleventh-century illuminated collection of saints lives for the month of January that Henry Walters acquired in 1930. See Georgi R. Parpulov, “A Catalogue of the Greek Manuscripts at the Walters Art Museum,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 62 (2004): 83–88.

But before the Blisses could visit Hungary, Mildred Bliss became seriously ill with pneumonia in Prague sometime after mid-February. Robert Bliss, therefore, visited the Tylers in Budapest on his own, and then Robert Bliss and Royall Tyler visited Vienna together. After Mildred Bliss’s recovery in mid-March, the Blisses returned to Paris and then visited Edith Wharton at Sainte-Claire du Château in Hyères in April before sailing for Naples and journeying on to Rome for Easter.See Edith Wharton to Beatrix Jones Farrand, April 4, 1936, and April 17, 1936, Edith Wharton Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. (Royall Tyler had wired Mildred Bliss suggesting that the Blisses seek advice about an Eastern Orthodox Easter mass in Rome from Guillaume de Jerphanion, the author of Une nouvelle province de l’art byzantin: Les eglises rupestres de Cappadoce,Guillaume de Jerphanion, Une nouvelle province de l’art byzantin: Les eglises rupestres de Cappadoce (Paris: P. Geuthner, 1925). a book he recommended that they buy.)

After Rome, the Blisses visited Mary and Bernard Berenson at their estate, Villa I Tatti, near Florence. On June 2, 1936, Elisabetta (“Nicky”) Mariano (1887–1968), Berenson’s secretary and lover, wrote Edith Wharton: “I got quite into the habit of having very pleasant conversations with Mr. Bliss, as I was put next to him at one lunch party after the other and found him very agreeable. I liked her less, she seemed to me affected and priggish but as all her friends praise her so much there must be certainly very delightful qualities under that ‘rare bird’ surface.”See Nicky Mariano to Edith Wharton, June 2, 1936, Wharton mss., Elisina Tyler correspondence, box, 11, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. Royall Tyler provided letters of introduction for Wolfgang Friedrich (“Fritz”) Volbach in Rome (“He speaks, more or less, French, and a lot of it.”)Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, March 27, 1936. He also insisted:

In Florence, dearest Mildred, do call up my Greek friend, Anna Levi.Anna Cosadino (Kosadinou) Levi (1895–1981), wife of the art historian and archaeologist Doro Levi (1899–1991). She was born in the Greek section of Istanbul and married Levi in 1928. See Giovanna Bandini, Lettere dall’egeo: Archeologhe italiane tra 1900 e 1950 (Florence: Giunti, 2003), 92n29 and 122n3. Her husbandTeodoro (“Doro”) Davide Levi (1899–1991), an Italian art historian and archaeologist. is a very distinguished archaeologist, Univ. professor, who has done a lot of digging in Crete, Mesopotamia etc etc. She was Anna Cosadino, of the family (orig. Gozzadini from Bologna) who were Lords of Keos (one of the Cyclades) from the 13th cent, until the Greek Independence. She has a marvellous eye for a work of art, and is a person of great distinction in all sorts of ways. They live 18 via Andrea da Castagno, Tel. 51234. I’ve written them that you may call up. She would show you the sort of things we like in the Bargello, the Opera del Duomo, the Laurenziana. She speaks excellent English.Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, March 27, 1936.

In the same letter, he also provided the Blisses with a checklist of buildings and artworks that they should see:

In Rome, I think you should spend some hours looking at the great brick buildings, ruins most of them, of the IIe–IIIe–IVe centuries, for it was out of them that came Santa Sophia. The baths of Caracalla, the so-called Minerva Medica (by the railway track, about 2 kilom. outside the Termini station, on the R. hand side leaving the station) and the Basilica of Constantine in the Forum. Of course you must also see the Mosaics of Sta. Maria Maggiore, SS. Cosme and Damiano, Sta. Pudenziana, The Lateran Baptistry, Sta. Prassède—and, among the IXe Cent. Roman mosaics—poor lot on the whole—Sta. Maria in Navicella (or in Domnica). Among the museums, don’t miss the little Museo Barracco, where there is A 1 Greek sculpture, and some Byz. slabs allied to the one you got at Stora’s.BZ.1936.44. In Naples, see the mosaics in the Cath. baptistery, and the chancel slabs in the little chapel of Sant’ Aspreno (now in the Bourse), and a carving in a side chapel of Sta. Maria Maggiore, allied to your (Stora) peacock.BZ.1936.19.

The Blisses sailed to the United States from Naples on April 28.

Royall Tyler traveled to Greece and Istanbul in October 1936 to experience an “orgy of mosaic! In the last week Saloniki, Hosios Loukas,Hosios Loukas, an historic monastery in Boeotia, Greece, which is an important monument of architecture and mosaics in Middle Byzantine art. Daphni,Daphni, an eleventh-century Byzantine monastery with mosaics that is located northwest of downtown Athens. and today everything that has been uncovered in S. Sophia, Constantinople! Marvels. I’ll report fully later.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, September 30, 1936. In Istanbul, Tyler saw firsthand the Byzantine mosaics at Hagia Sophia, which had been recently uncovered by the Byzantine Institute under the direction of Thomas Whittemore. Tyler’s lengthy, full report to Mildred Bliss of October 11, 1936, detailed every mosaic then uncovered in the church. He interjected halfway through his narrative on the mosaics: ”By the way, this story—and everything else in this letter—is highly confidential. W. begged me to regard all I saw as confidential. I can’t believe he meant it literally, but you know him and can judge. I pass the seal of secrecy on to you.”

Edith Wharton

The Blisses’ visit with their friend, the American novelist Edith Wharton at Sainte-Claire du Château in Hyères in April 1936 would be the last time that they would see her. Her health had begun to decline already in 1935, but she became seriously incapacitated in 1937. Beginning in the summer of that year, Elisina Tyler remained with her constantly. In a letter of July 25, 1937, Royall Tyler wrote Robert Bliss:

It is infinitely distressing to see Edith fading away. Elisina is standing it well, but she looks pretty thin, & I’m a bit anxious. But, at this time, she couldn’t stand being anywhere else. As you may imagine, there are constantly questions coming up about the place at St. Brice, the place at Hyères, which it would be extremely dangerous to have Edith worried about, but which would fatally be taken to her if Elisina were not here. As it is, Edith is quiet & happy & comfortable, not suffering, not worrying.

In August, Edith Wharton suffered a stroke and was paralyzed on her left side.Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, August 9, 1937. She died on August 11. Wharton named Elisina Tyler the executor of her French will and left her the château at Hyères. She also left to her financial interests from her American estate,This consisted mainly in home mortgages, the value of which was difficult to estimate and which would have been difficult and costly to liquidate. a bequest that was disputed by Wharton’s niece, Beatrix Farrand. This inheritance quickly became financially untenable, as the correspondence amply chronicles. Elisina had to pay inheritance tax on the Hyères property amounting to forty percent of its assessed value. In order to pay for maintenance, the wages and gratuities of the servants, and other expenses, as well as the inheritance tax, Elisina was forced to mortgage the property as well as to borrow from the bank. As Royall Tyler pointed out in a letter to Mildred Bliss of June 18, 1938:

The prospect now is that unless the whole sum which was the object of the settlement above referred to goes to Elisina, the result of her having been appointed residuary legatee by E. W. will be to involve Elisina in a financial loss, even allowing for what Elisina stands to get under the American residuary legateeship. Bill will stand to receive from his parents less than he would have received had E. W. not mentioned Elisina in her will.

The strain of all this was perhaps directly responsible for Elisina Tyler suffering in May 1938 what was referred to as “an attack of apoplexy,” perhaps a mild stroke that affected her speech. Royall Tyler wrote Mildred Bliss on June 18, 1938: “I have had a full report from her doctor, who attributes the attack to overwork and anxiety during the last year. He says she will recover, provided she is protected from all anxiety for some months to come. But the facts of the position are known to her and can hardly fail to prey on her mind.” Mildred Bliss replied on July 29, 1938:

And now, my dear, for Elisina. The picture you have drawn catches me at the throat. The finality of the milestone passed is frightening and seems to put one into another gear. How one wishes none of this wretched business had been!—How one regrets the price. How twisted and unhappy it all is and how different from what poor Edith would have wished. I am thankful to learn from B.F. that a settlement has been reached on a fifty-fifty basis which I suppose is not thoroughly satisfactory to either party but it is better than uncertainties, and to have the chapter closed was desirable. Now that I know Elisina is convalescing and able to have a friend or two stop with her, and by going slowly enjoy a portion of the day, I shall write her again but not dwell too much on what has befallen her even by implication, and you will keep me well informed, won’t you, of any change that occurs.

Publications

Throughout this period, Royall Tyler and Hayford Peirce worked on the third and fourth volumes of their proposed five-volume edition, L’art byzantin, which, like the first two volumes, were to be published by the Librairie de France. By January 1937, the completed text of the third volume had been edited and prepared in galley proofs and the plates had been printed. But by August 1937, the Librairie de France had gone out of business due to the Depression and its stock was taken over by the Librairie Gründ. This transition put plans for the publication on hold, and with the eventual outbreak of war, the possibility of bringing the book to publication became increasingly less certain. In 1940, Hypérion bought the rights to publish a second edition of L’art byzantin that combined the first three volumes, and the publishing house planned to offer this combined edition in French, English, and German versions. But the fact that the plates were impounded in Occupied France and that their exact whereabouts were unknown also made this plan impossible. No further volumes of L’art byzantin would be published.

Unexpectedly, after twenty-two years, in January 1937, the Public Record Office of the British Home Office in London decided to revive the Spanish Calendar of State Papers project and sent Royall Tyler the proofs for the twelfth volume, January–July 1554. But again due to world conditions, this volume would not be published until 1949. The thirteenth and last volume, July 1554–November 1558, would be published posthumously in 1954.

In 1938, the Blisses began planning for a periodic publication, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, which would be devoted to Byzantine studies, especially Byzantine art. They invited Royall Tyler to submit an article for the first volume, which they hoped to bring out in February 1939. Tyler chose the subject of the Dumbarton Oaks “Elephant-Tamer Silk,”BZ.1927.1. because, as he wrote Mildred Bliss on July 10, 1938, it was an artwork “unpublished, unique, mysterious, and coming from that intriguing no man’s land, the VIIIe-lXe centuries. Of course you have many more imposing things, but they’ve either been published before, or fit in perfectly with other well-known material. Not that there won’t be plenty to say about them, but the Elephant-tamer is a virgo intacta,“Untouched.” and I think in every way suitable to head the list. I hope you agree.” But once again publication plans were postponed, and although he completed the text by July 20, 1938, the article would not be published until 1941Hayford Peirce and Royall Tyler, “Elephant Tamer Silk, VIIIth Century,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 2 (1941): 19–26. in the second volume, a volume devoted to three studies by Hayford Peirce and Royall Tyler. In planning for the first volume, Mildred Bliss questioned whether Tyler might not want to author the article himself and not publish it as coauthored by Hayford Peirce. She wrote him on July 29, 1938:

We are delighted and touched that you were willing to make the great effort of writing the first paper. As for the signature, . . . I wondered if Hayford himself wouldn’t see, and be rather amused and touched than otherwise, that we wanted, for sheer sentiment’s sake, to have Dumbarton Oaks make its first bow to the reading public over your signature alone—just this once. What do you think? Would he understand or would he be hurt?

Royall Tyler was steadfast, however. He and Hayford Peirce had spent over ten years acquiring, studying, and publishing Byzantine art together, and he wanted to see both of their names in the inaugural volume of the Dumbarton Oaks Papers. In doing this, he saw that their joint contribution to the publication would signal the culmination of their friendship and teamwork and represent the pinnacle of their association with the Blisses, their Byzantine collection, and their research institution, which they had been instrumental in helping to create. Tyler wrote to Mildred Bliss: “But I hope very much you’ll agree to the paper being done by the Old Firm. In effect, it will all be mine—but . . . you know how one feels.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, July 10, 1938.