Coolidge Auditorium

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge translated her early love of music into widespread support for the Music Division of the Library of Congress, including the Coolidge Auditorium.

Practically everyone loves chamber music who understands it; and . . . almost everyone understands it who hears it enough.

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge

Despite being only moderately wealthy, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (1864–1953) nevertheless played an important role in championing music in twentieth-century America. Her philanthropic gifts to the Music Division of the Library of Congress resulted in the construction of the Coolidge Auditorium, the endowment of the Coolidge Foundation, and the expansion of the Music Division’s manuscript collection. More importantly, her vision and persistent endeavors directly led to the advancement of chamber music commissions and performances in America.

A Musical Childhood

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge was born in 1864 to Albert Arnold and Nancy Ann Atwood Sprague, a wealthy and respected family. After graduating from Yale University, Albert Arnold Sprague moved to Chicago, where he established a successful wholesale grocery chain and eventually sat on the board of the Chicago Symphony and the Art Institute of Chicago.Cyrilla Barr, “The Faerie Queene and the Archangel: The Correspondence of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge and Carl Engel,” American Music 15, no. 2 (Summer 1997): 160. His wife was a talented musician who inspired Coolidge’s own music-making interest.Cyrilla Barr, The Coolidge Legacy (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1997), 10.

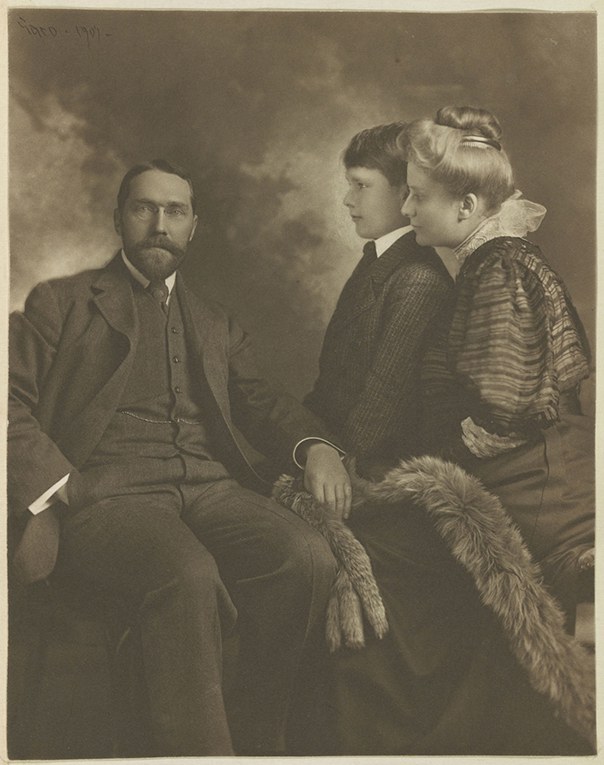

As a child, Coolidge excelled at piano, studying seriously at the studio of Mrs. Regina Watson, a student of the Polish pianist Carl Tausig. She soon aspired to pursue a career in piano performance, a dream that was no doubt propelled further by her family’s close relationship with the famous female pianists Theresa Carreno and Fanny Bloomfield Zeisler.Cyrilla Barr, “The Musicological Legacy of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge” The Journal of Musicology 11, no. 2 (Spring 1993): 251. However, her social standing as a member of Chicago’s elite society barred Coolidge from ever having so public a career, and instead, she found outlets for her talent in Chicago’s women’s clubs, where she performed, composed, and even lectured.Barr, “Musicological Legacy,” 251. Although Coolidge’s first love would always be performing, her broader experiences with music history and composition shaped her philanthropy. In 1891, Elizabeth Sprague married Frederic Shurtleff Coolidge (1865–1915), a Harvard graduate and orthopedic surgeon.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 14.

Tragedy and Philanthropy

Tragedy struck in 1915 and 1916, when Coolidge’s father, mother, and husband died. Her first philanthropic endeavors would surface during this period. A week after her father’s death, Coolidge established a $100,000 pension fund for the Chicago Symphony in his name, an act that cut her own family inheritance in half. She contributed to the building of a hospital for tuberculosis treatment in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, as a tribute to her husband, and gave over her own Chicago home to be used as a nurses’ residence.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 14–15.

The Berkshire Quartet

Coolidge’s active involvement in the American music scene formally began with her sponsorship of the Berkshire Quartet. In May 1916, Coolidge received a letter from Hugo Kortschak (1884–1957), an Austrian violinist who wanted to leave the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the hopes of starting his own string quartet. Coolidge supported the idea enthusiastically, traveling to Chicago to hear the quartet after which she offered the performers a contract.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 15, 17.

In 1917, Coolidge built the Berkshire Quartet a performance venue, the Temple of Music, at Pittsfield in the Berkshire mountains. She also founded the Berkshire Festival as well as a string quartet competition that awarded a cash prize, the Berkshire Prize.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 17. Coolidge collected the holograph manuscripts of the prize winners as well as commissioned composers, building a small but impressive autograph musical manuscript collection. Coolidge soon realized, however, that so long as she served as the sole judge and planner, the Berkshire Festival, no matter how successful, would not survive her eventual death.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 19. (In fact, the last Berkshire Festival for chamber music occurred in 1938.Lenox History, “Before There was a Tanglewood Music Festival.” https://lenoxhistory.org/lenoxhistorypeopleandplaces/lenoxhistorypeople/the-berkshire-music-festival (accessed July 18, 2017). The Berkshire Festival was replaced by Gertrude Smith’s Berkshire Symphonic Festival (predecessor to the Tanglewood Music Festival), to which Coolidge contributed but was not a founder.) Faced with this dilemma, Coolidge next sought to direct her philanthropy in a manner that would be “institutionalized and impersonalized . . . not to be dependent on the life, the good will, or the bank account of any individual.”Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, “Da Capo” (a paper read before the Mothers’ Club, Cambridge, Massachusetts, March 13, 1951).

The Library and Congress and Coolidge Auditorium

Always anxious to increase the treasures which are entrusted to my care at the Library of Congress I would like to ask you if you have given any thought to the ultimate disposal of your prize autographs. It would seem but fitting that your fine collection be someday placed with our National Library, as a permanent testimony to the ideals and munificence of a remarkable American woman.Barr, “Faerie Queene,” 161.

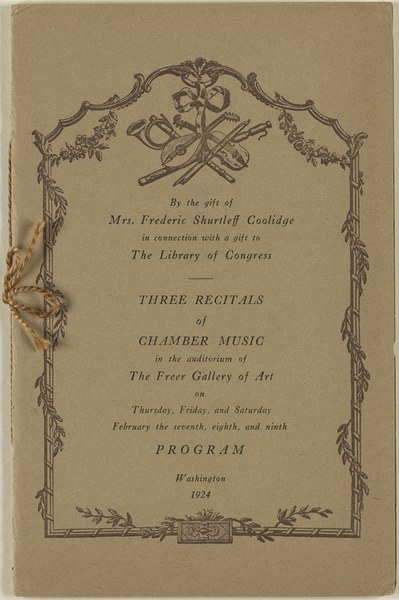

Coolidge gifted her collection to the Music Division of the Library of Congress shortly after receiving Engel’s letter with the explicit desire to have her scores performed at the Library of Congress by the winning quartet of the Berkshire Festival. Coolidge thus combined her interests in the historical preservation of contemporary music with its live performance. The Library of Congress, however, had no performance venue. Engel therefore arranged for the concerts to take place at the Freer Gallery of Art. These concerts took place in February 1924, a year and a half after Engel’s first letter. Moreover, their success encouraged Coolidge to envision the construction of a permanent performance space at the Library of Congress itself.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 19–21.

The construction of the Coolidge Auditorium required the passing of a legislative bill before it could begin, and in a November 1924 letter to Congress to support this bill, Coolidge wrote:

In pursuance of my desire to increase the resources of the Music Division of the Library of Congress, especially in the promotion of chamber music . . . I offer to the Congress of the United States, the sum of $60,000 for the construction and equipment of an auditorium which shall be planned for and dedicated to the performance of chamber music, but shall also be available . . . for any other suitable purpose, secondary to the needs of the Music Division.Barr, “Faerie Queene,” 166.

President Calvin Coolidge signed the auditorium legislative bill into law on January 25, 1925.Barr, “Faerie Queene,” 166.

Construction of the Auditorium

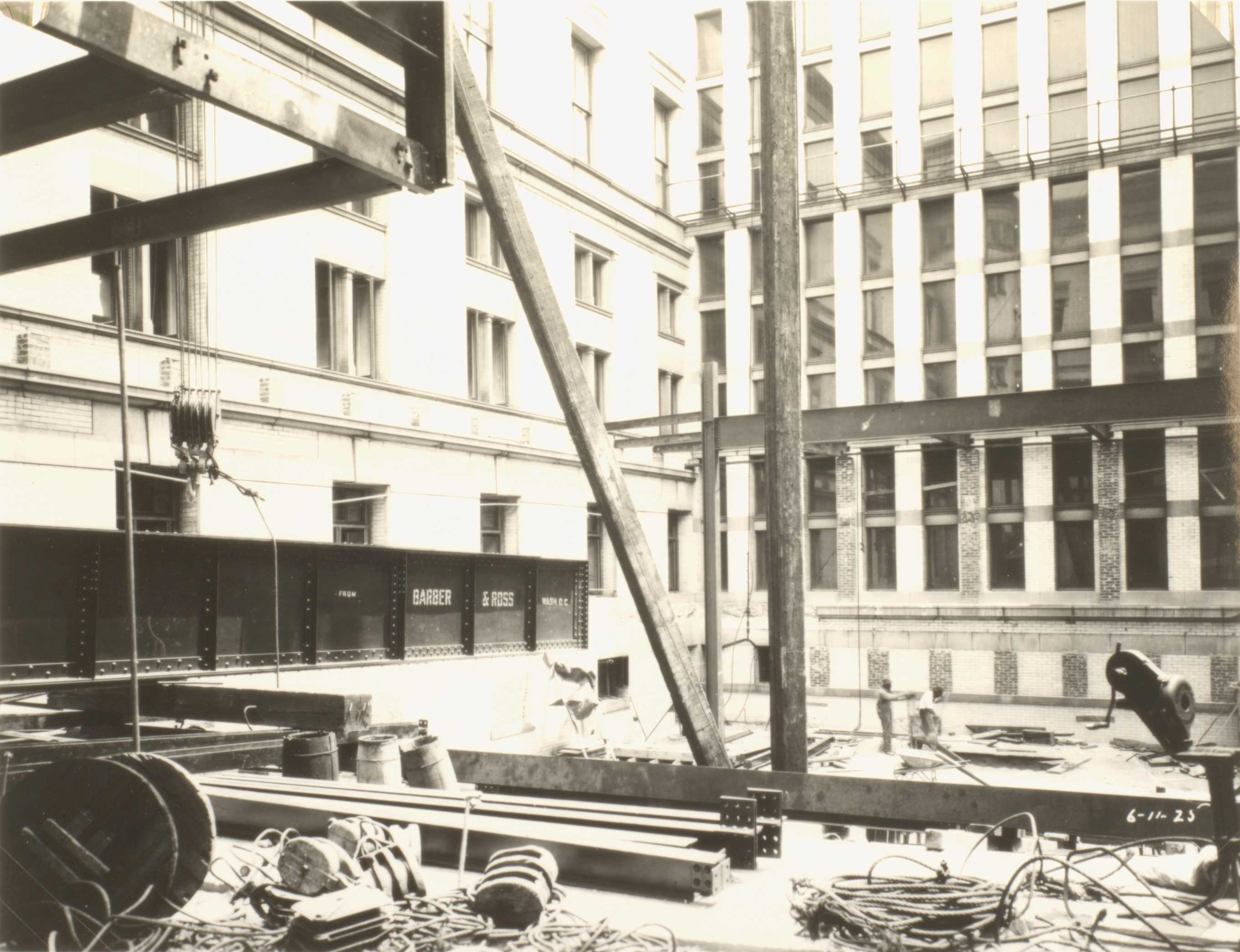

Because Coolidge was away in Europe during most of the auditorium’s construction, she left Engel in charge of its completion and dedication. Coolidge imagined an auditorium of “chaste beauty” without any extraneous “ornate display.” She wanted a concert hall solely dedicated to the needs of chamber music. The Coolidge Auditorium’s size, sight lines, acoustics, and stage were therefore specifically designed to emphasize chamber music’s unique intimacy and smallness of scale.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 22, 24.

Despite Coolidge’s initial rejection of the purely decorative, the auditorium’s final design notably incorporated several of Engel’s preferences in its location and aesthetics. Per Engel’s suggestions, the concert hall was built into a courtyard already attached to the Music Division which cut costs associated with land, ventilation, lighting, and heating.Barr, “Faerie Queene,” 167. Additionally, Engel’s original plans for a terrace on the auditorium’s rooftop evolved into the space’s current courtyard featuring a pool with blue and green faience tiles. To preserve Coolidge’s legacy, Engel commissioned a marble bas-relief sculpture of Coolidge in profile. This sculpture, along with Gary Melcher’s portrait of Coolidge and her son, sit in the auditorium’s foyer as a tribute to Coolidge’s extensive dedication to the performance and shared experience of music.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 24.

Coolidge also insisted that the auditorium be equipped for radio broadcast, because, as she stated, “practically everyone loves chamber music who understands it; and . . . almost everyone understands it who hears it enough.” The concert series were broadcast by the Columbia, National, and Mutual Broadcasting Companies.“The Eagle Sings,” in “Chamber Music: The Life and Legacy of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge,” Library of Congress, accessed July 18, 2017, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/elizabeth-sprague-coolidge-chamber-music/eagle-sings.html.

The Coolidge Auditorium’s Continuing Legacy

With the completion of the space in 1925, Coolidge asked Engel to plan the first Library of Congress Festival for the Coolidge Auditorium’s dedication. The festival ran for three days through Coolidge’s birthday on October 30, which Engel established as Founder’s Day. In preparation for the Festival, Coolidge sponsored competitions and commissioned works by Charles Martin Loeffler, Frederick Stock, and Ildebrando Pizzetti. Engel also designed the festival logo: a bald eagle holding Apollo’s lyre.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 26–27.

Throughout the festival’s many commissions, Coolidge and Engel fervently argued over the merits of American or European composers, leading to the festival’s support of notable contemporary works from both cultures. The Library of Congress Festivals notably premiered Apollon Musagète by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971). More famously, Coolidge commissioned and premiered Aaron Copland’s (1900–1990) ballet Appalachian Spring that was both choreographed and danced by Martha Graham (1894–1991) at the tenth Library of Congress Festival.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 27, 29. Graham praised Coolidge’s commitment to innovation in the arts:

You have been a name to me for so long, a name that was a force for faith in creative effort. . . . Then when you told me your plan I realized that this was not only a ‘first’ for me but for American dance as well. To my knowledge this is the first time that a commissioning of works for the American Dance has ever happened. It makes me feel that the American dance has turned a corner, it has come of age.Martha Graham to Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, August 2, 1942. “Ballet for Martha,” in “Chamber Music: The Life and Legacy of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge,” Library of Congress, accessed July 18, 2017, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/elizabeth-sprague-coolidge-chamber-music/ballets-for-martha.html.

To date, the Coolidge Auditorium itself has featured some of the twentieth-century’s foremost artists including Leonard Bernstein, Nadia Boulanger, Samuel Barber, and Arthur Rubinstein. Renowned string quartets including the Budapest, the London, and the Juilliard have performed on its stage. The auditorium has hosted over twenty thousand concerts, ensuring the continuing growth of modern chamber music compositions and their performance.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 26.

In 1925, the year of the first Library of Congress Festival, Walter Wilson Cobbett (1847–1937), an Englishman with a passion for music, awarded Coolidge the Cobbett medal for her services to chamber music. This honor inspired Coolidge to inaugurate the Coolidge medal on Founder’s Day in 1932, an award presented to patrons of chamber music for their “eminent services” in supporting the genre. Eventually discontinued by the Library of Congress in 1948 along with similar awards in the fine arts, the Coolidge medal celebrated the contributions of twenty-five patrons during Coolidge’s lifetime.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 28–29.

The Coolidge Foundation

In October 1924, as Coolidge’s plans for the Coolidge Auditorium were developing, she sought to establish an endowment at the Library of Congress that would cover the Music Division’s operational costs and expand its manuscript collection. Despite the fact that no legislative precedent existed for the creation of a trust fund at a government-administered institution,Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 21. Congress established the Library of Congress Trust Fund Board, and President Coolidge signed the endowment into law on March 3, 1925.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 30.

With the passing of the trust fund bill, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge transferred $400,000 in principal to the Library of Congress, which would guarantee the Music Division an annual interest income of $28,000. She clearly stipulated the purpose of the trust fund was “[to] conduct periodic festivals, give concerts and defray the expenses thereof, offer and award prizes for original compositions, pay an honorarium to the Chief, and further the cause of musicology.”Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 30.

Additionally, a board of directors consisting of the secretary of the treasury, chairman of the Joint Committee on the Library, Librarian of Congress, and two members appointed by the President was established to oversee the use of the trust fund.Ibid. Coolidge gave the board great flexibility in their decision making, allowing “any and all . . . acts and things designed to promote the art of music, so far as any of the foregoing purposes come within the charitable uses which are allowed and can be sustained by law.”Library of Congress, Report of the Librarian of Congress, For the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1925 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1925), 3.

At the beginning of its existence, the foundation supported the Library of Congress Festivals, which allowed the public to participate free of charge, a Coolidge initiative to prevent the performances from being exclusive to elite social circles. Additionally, the foundation sponsored public concerts in different venues around the country and funded tours for European artists debuting their compositions in the United States.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 32.

Coolidge sought to promote chamber music for the benefit of both artists and audience members alike. In her correspondence with Herbert Putnam (1861–1955), the Librarian of Congress at the time, Coolidge explained her intentions in establishing the foundation. She hoped that it would

make possible, through the Library of Congress, the composition and performance of music in ways which might otherwise be considered too unique or too expensive to be ordinarily undertaken . . . as an occasional possibility of giving precedence to considerations of quality over those of quantity; to artistic rather than to economic values; and to opportunity over expediency.“Foundations for Music,” Library of Congress, accessed July 18, 2017, https://www.loc.gov/rr/perform/guide/fndmus.html.

Achievements of the Coolidge Foundation

Throughout the years, the Coolidge Foundation has commissioned many works, including pieces for chamber orchestra by Anton Webern, Heitor Villa-Lobos, Igor Stravinsky, Maurice Ravel, and Sergei Prokofiev. Additionally, Coolidge personally commissioned and received dedications from many composers throughout her lifetime, including Frank Bridge, Benjamin Britten, Rebecca Clarke, and Paul Hindemith. In all, Coolidge sponsored over two hundred works through her festivals, Foundation, and personal commissions.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 53.

More broadly, the establishment of the Coolidge Foundation set a legislative precedent for additional foundations at the Library of Congress. To date, the Library of Congress’s Music Division manages sixteen trust funds including the Katie and Walter Louchheim Fund established in 1968, the Kindler Foundation Trust Fund created in 1983, and the Carolyn Royall Just Fund inaugurated in 1992, all for the continuation of chamber music ranging from the classical to the contemporary. Now one of many, the trust fund that started it all, the Coolidge Foundation, still exists to support commissions, lectures, exhibits, and concerts at the Library of Congress.Barr, Coolidge Legacy, 53.

Profile by Julia Lu, 2017 summer intern, and James N. Carder, Archivist and House Collection Manager.