National Gallery of Art

Andrew W. Mellon hoped that the National Gallery of Art would be a “joint enterprise on the part of the Government . . . and of magnanimous citizens,” an ambition realized with donations by the eight Founding Benefactors.

Over a period of many years I have been acquiring important and rare paintings and sculpture with the idea that ultimately they would become the property of the people of the United States.

Andrew W. Mellon

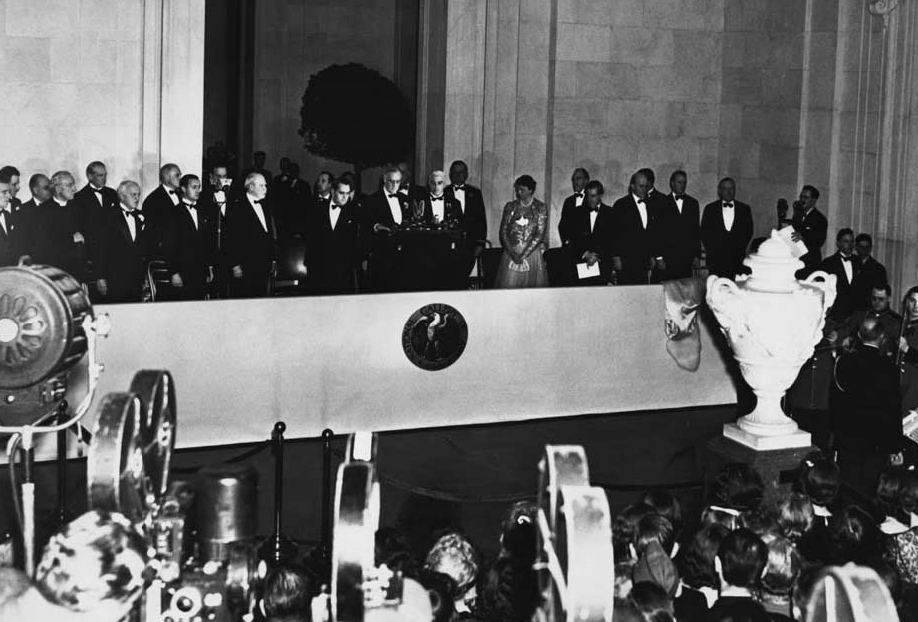

Andrew W. Mellon, who pledged both the resources to construct the National Gallery of Art as well as his high-quality art collection, is rightly known as the founder of the gallery. But his bequest numbered less than two hundred paintings and sculptures—not nearly enough to fill the gallery’s massive rooms. This, however, was a feature, not a failure of Mellon’s vision; he anticipated that the gallery eventually would be filled not only by his own collection, but also by additional donations from other private collectors. By design, then, it was both Andrew Mellon and those who followed his lead—among them, eight men and women known as the Founding Benefactors—to whom the gallery owes its premier reputation as a national art museum. At the gallery’s opening in 1941, President Roosevelt stated, “the dedication of this Gallery to a living past, and to a greater and more richly living future, is the measure of the earnestness of our intention that the freedom of the human spirit shall go on.”President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “The President's Address delivered at the Dedication Ceremonies on March 17, 1941,” 6, National Gallery of Art, accessed August 11, 2017, https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/gallery-archives/PressReleases/1949-1940/1941/14A11_43509_19410317.pdf.

Over the three-quarters of a century since its founding in 1941, the National Gallery of Art has amassed one of the world’s most significant collections of European and American paintings, sculptures, decorative arts, prints, drawings, and photographs.“Recent Acquisitions,” National Gallery of Art, accessed August 11, 2017, https://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/recent_acquisitions.html. From its beginning with Andrew Mellon’s gift of 152 paintings and sculptures, the collection has grown to more than 145,000 artworks. The National Gallery of Art states that its mission is “to preserve, collect, exhibit, and foster understanding of works of art.”“Recent Acquisitions,” National Gallery of Art. In 2014, the gallery signed an agreement with the Corcoran Gallery of Art for the stewardship of the Corcoran art collection after that museum closed for financial reasons.“Highlights of the History of the National Gallery of Art,” National Gallery of Art, accessed August 4, 2017, https://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/research/gallery-archives/nga-history-timeline.html.

The Nation’s Art Gallery

Private collections that had become public museums existed in Washington before the creation of the National Gallery of Art. By the 1930s, Washington was home to several: the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Phillips Collection, and the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery. These collections were somewhat modest, however, when compared to the national art museums in London, Paris, and Berlin. Andrew Mellon’s gift of his art collection in 1937 and the opening of the gallery in 1941 “provided the city with instant status in the museum world, and helped call attention to its growing cultural charms.”Neil Harris, Capital Culture: J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art, and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013), 2. A Smithsonian National Gallery of Art also existed at the time of the founding of the National Gallery. However, it lacked a permanent building after a fire at the Smithsonian Castle in 1865 made the Smithsonian reluctant to have art collections there. Much of the collection was put on loan at the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Library of Congress. When the National Gallery was chartered, the Smithsonian National Gallery was renamed the National Collection of Fine Arts and was again renamed the National Museum of American Art in 1980. “Museum History,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, accessed August 4, 2017, http://americanart.si.edu/visit/about/history/.

Andrew W. Mellon and the Founding of the National Gallery

Although Andrew Mellon had been collecting paintings since the turn of the century,David Canadine, “Andrew W. Mellon,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, accessed August 4, 2017, https://mellon.org/about/history/andrew-w-mellon/. it was in Washington that he began to considerably increase the size of his collection while at the same time narrowing its scope and improving its overall quality. To do this, he especially relied on two art dealers that he had first patronized while in Pittsburgh: Charles Carstairs of M. Knoedler & Co., New York, and Joseph Duveen of Duveen Brothers, London, Paris, and New York. Both dealers seized the opportunity to offer Mellon Old Master paintings of the highest quality. Mellon, for his part, grew ever more resolute about which artworks he wanted for his collection and became “more knowledgeable and decisive about the direction of his collecting interests than is generally recognized.”Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., “A History of the Dutch Painting Collection at the National Gallery of Art,” in Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century, NGA Online Editions (Washington, D.C., 2014), accessed July 28, 2017, https://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/research/online-editions/17th-century-dutch-paintings/essay-history-dutch-paintings-nga.html. By the early 1930s, Mellon had amassed the greatest collection of Old Master canvases and British portraits of his generation.Canadine, “Andrew W. Mellon.” Most notably, in 1930 and 1931, he purchased twenty-one highly important paintings from the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad through M. Knoedler & Co.John Walker, The National Gallery, Washington (London: Thames & Hudson, 1964), 24–26.

Mellon had begun to formulate a plan to establish a national art museum in the nation’s capital as early as 1928, and his collecting in the 1920s and 1930s was aimed toward the eventual establishment of a public gallery.Philip Kopper and the Publishing Office of the National Gallery of Art, America’s National Gallery of Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 17. He stated as much in a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936, in which he formally offered to donate his art collection and fund the construction of the National Gallery of Art:“Highlights of the History of the National Gallery of Art,” National Gallery of Art.

Over a period of many years I have been acquiring important and rare paintings and sculpture with the idea that ultimately they would become the property of the people of the United States and be made available to them in a national art gallery to be maintained in the City of Washington for the purpose of encouraging and developing a study of the fine arts.Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Excerpts from Letters with Andrew W. Mellon on the Gift of an Art Gallery to the United States,” December 22, 1936. Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, accessed August 4, 2017, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15334. It has been speculated that Mellon used the offer of the National Gallery to “pay off” President Roosevelt, as Mellon was at the time under investigation for tax fraud. Despite this accusation, for which he was eventually exonerated, Mellon persisted with his plan and wrote: “I am not going to be deterred from building the National Gallery in Washington. Eventually the people now in power in Washington will be dead and I will be dead, but the National Gallery, I hope, will be there and that is something the country needs.” David E. Finley, A Standard of Excellence (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1973), 35–7.

The government acted swiftly to accept his offer, and in 1937 Congress passed legislation to formally establish the National Gallery of Art.

An Example for Others

Andrew Mellon hoped that his gift would attract other gifts of equal significance. His son, Paul Mellon (1907–1999), recalled at the 1941 dedication of the gallery, “[my father] hoped that the gallery would become a joint enterprise on the part of the Government, on the one hand, and of magnanimous citizens, on the other.”Paul Mellon, “Mr. Paul Mellon’s Speech, National Gallery of Art Dedication,” 1, National Gallery of Art, accessed August 4, 2017, https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/gallery-archives/PressReleases/1949-1940/1941/14A11_43512_19410317.pdf. To encourage others to donate, Mellon refused to have the gallery named after him. As Roxanne Roberts of the Washington Post wrote in her coverage of the gallery’s seventy-fifth anniversary, “he insisted that it be called the National Gallery of Art—it was his gift to the nation, not a monument to himself, and he wanted it to inspire others.”Roxanne Roberts, “The National Gallery Celebrates 75 Years, Thanks to Old-Fashioned Philanthropy,” Washington Post, April 7, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/the-national-gallery-celebrates-75-years-thanks-to-old-fashioned-philanthropy/2016/04/07/9f0df7d6-fce6-11e5-80e4-c381214de1a3_story.html. At the dedication of the gallery, President Roosevelt lauded Mellon’s intentions: “The giver of the building has matched the richness of his gift with the modesty of his spirit, stipulating that the Gallery shall be known not by his name but by the nation’s.”Roosevelt, “President’s Address,” 1.

Andrew Mellon did not live to see the dedication of the gallery. He died in August 1937, within twenty-four hours of the death of John Russell Pope, the architect who designed the gallery’s West Building. His posthumous bequest to the gallery comprised one hundred and twenty-six paintings and twenty-six works of sculpture.

A Collection of “a High Standard of Quality”

Mellon’s collecting strategy and vision for the National Gallery focused on the quality of the artworks. In his 1936 letter to Roosevelt, he made this explicit:

It is of the greatest importance that future acquisitions of works of art, whether by gift or purchase, shall be limited to objects of the highest standard of quality, so that the collections to be housed in the proposed building shall not be marred by the introduction of art that is not the best of its type.Finley, Standard of Excellence, 48.

To ensure that the museum would only include works of the highest caliber, Mellon proposed in his bequest, and Congress then stipulated, that no work should ever be added to the gallery “unless it be of a similar high standard of quality” as the Mellon bequest.“Andrew W. Mellon,” National Gallery of Art, accessed August 4, 2017, https://www.nga.gov/collection/gallery/ggfound/ggfound-987.0.html. House Joint Resolution 217, section 5 (b), 75th Congress, specifies that “In order that the Collection of the National Gallery of Art shall always be maintained at a high standard and in order to prevent the introduction therein of inferior works of art, no work of art shall be included in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Art unless it be of similar high standard of quality to those in the collection acquired from the donor [Mr. Mellon].

The Founding Benefactors

Mellon laid the groundwork for the gallery and established a vision for the future, but his donation was not remotely sizable enough to fill the grand building he had created.Wheelock Jr., “Dutch Painting Collection.” Over the course of the gallery’s next four decades, other donors formed and gave impressive collections—donations that dwarfed the size and scope of Mellon’s original bequest. Eight of these donors, along with Andrew Mellon, are known as the Founding Benefactors; they are Samuel Henry Kress and Rush Harrison Kress, Peter Arrell Brown Widener and Joseph Early Widener, Lessing Julius Rosenwald, Chester Dale, Ailsa Mellon Bruce, and Paul Mellon.

Profile by Noah Houghton, 2017 summer intern, and James N. Carder, Archivist and House Collection Manager.