Museums mark the streets. Their names are familiar; emblazoned on brick walls or carved into stone plinths, they summon up notions of extensive collections, tastefully displayed, that emanate the mute grandeur of faits accomplis. The beauty of the objects seems to seal them in the moment. But we hardly give a thought to the personal passions that chose this painting, that vase, or the quirks and whims that stocked the galleries and that, in many cases, still guide the collections.

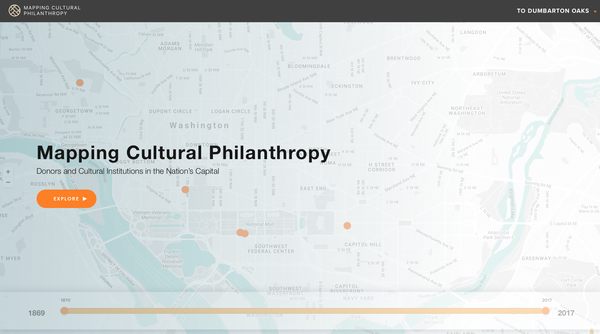

The effort to examine the founding philosophies of some of Washington, D.C.’s renowned cultural institutions is at the heart of Dumbarton Oaks’ Mapping Cultural Philanthropy project, which launched earlier this year. The project, in development since 2016, presents an online mapping tool featuring rigorously researched entries on institutions like the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Freer and Sackler Galleries, and the Folger Shakespeare Library. The entries describe not only the institutions and collections themselves, but also the personalities—grand or self-effacing, minutely focused or broadly piqued—that brought them into existence.

“What we’re not doing, by design, is chronicling people that gave a lot of money but otherwise weren’t impassioned about their collecting,” Dumbarton Oaks Archivist James Carder, who has supervised the project since its inception, explains. “To make our list you really do have to have had a passion for the arts, theater, music—anything in the arts and humanities. And you have to have made it happen in a public way.”

Teasing out the little-known backstories of D.C.’s museums and collections reveals a web of philanthropic activity. As Carder explains, the project, initiated by Director Jan Ziolkowski, sprang from a desire to contextualize the beginnings of Dumbarton Oaks and similar institutions in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. “We wanted to map what had happened in Washington, D.C., not only to better understand who the Blisses were and what milieu they moved in,” Carder says, “but also to show that Washington was an important nexus for, frankly, wealthy and passionate collectors who wanted to make those collections part of the public landscape.”

In many ways, the private philanthropy of the mid-twentieth century continued the thread of nineteenth-century philanthropic endeavors, though this began to change as the century waned. In charting this evolution, the project gels nicely with recent efforts by Dumbarton Oaks, including its Wintersession course for undergraduates, to examine the changing face of philanthropy in the twenty-first century. “In the last part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, philanthropy has started to be redefined,” Carder explains. “We’ve entered into questions of effective altruism, so that private philanthropy has started to move away from the arts and humanities and into different, perfectly valid, and perfectly respectable fields, like medicine or education.”

The long-term project has seen contributions from a number of people, including a team of four interns during the summer of 2016. Recently, Humanities Fellow Priya Menon has worked to standardize some of the preexisting profiles in the catalog while also writing entries of her own. Her work has marked a shift into present-day studies, with a deeper focus on the use of primary sources. In developing an entry on the National Museum of Women in the Arts, for example, she had the opportunity to interview the collection’s founder, Wilhelmina Holladay, and has worked with other oral histories to develop profiles of more recently established cultural institutions.

“We’re really looking at private collections that eventually became public,” Menon explains, “and I’ve found that the project actually demonstrates that the public and the private can intersect in ways that are productive and even beautiful, and that care for future generations’ well-being—and that they’ve been doing this for a considerable length of time within the realm of art.”

Carder similarly pinpoints part of the project’s value in its illumination of the past and present, of the evolution of cultural philanthropy over time, and what these can tell us about the current climate of cultural institutions in D.C. The funding of a gallery or museum is typically piecemeal and complex. In addition to the legacy of the founding gift (which might include hobbling stipulations that disallow, for instance, the loaning of objects), many institutions run on a budget comprised of private donations, soft money made from museum shops, and, of course, federal money. “How all of that’s managed—and how the missions of these institutions are going to be effected—is really going to be fairly interesting in the coming years,” Carder says. “There are a number of institutions anticipating large cuts in federal funding. Right now, of course, these are just guesstimates—but who knows?”

After its launch, the project will continue to expand, adding new entries at a regular pace. Though the site’s current entries have benefitted from the use of secondary sources that lay out general histories and missions—prefaces to catalogs, for instance, or book-length studies of collectors like William Wilson Corcoran—future profiles will wade into what Carder deems “potentially problematic areas.” As the project shifts focus to more modern institutions and collectors, secondary sources will of course dry up, though all that means is a challenge, and the need to dig a little deeper. With plans to look at the founder of the Washington School of Ballet and a number of collectors who gave important instruments to the Library of Congress, future profiles will have to derive a little more from research and footwork, like the interview recently conducted with Holladay—“which is really the right way to go,” Carder says with a chuckle, “because she’s alive.”

The standardizing of the profiles—making sure one biographical section isn’t five paragraphs longer than another—has been helped along by Lain Wilson. As Digital Content Manager at Dumbarton Oaks, Wilson has helped advise the project, editing profiles and managing its design process. As Carder explains, “He’s been invaluable in terms of taking our suggestions and talking reality, and consistency, and length, and graphic style, and all the things that our pie-in-the-sky ideas hadn’t considered.” The result is a fluid interface—produced by Image Conscious Studios, an external firm—that will also double as the first phase in a broader restyling of Dumbarton Oaks’ main website.

As Wilson explains, the diversity of the project—its contributors, subjects, presentation, and approach—is built into its design. “The idea was always to have a flagship project that would run across several years and involve multiple cohorts of fellows and interns,” Wilson says. “The goal of building a project that speaks to Dumbarton Oaks’ institutional mission and history, and puts it in a broader context of cultural philanthropy in the D.C. area, is well served by many hands.”

Freer, Sackler, Folger, Corcoran—names that dot the map and bear stories of individuals with singular passions. As the Mapping Cultural Philanthropy project launches—and in the months ahead—they’ll share the digital grid with institutions like the Textile Museum, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Phillips Collection, and—of course—Dumbarton Oaks.