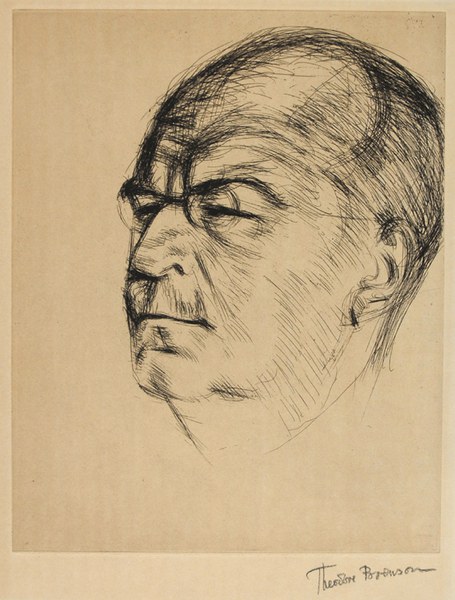

Henri Focillon (1881–1943) was the first senior scholar at Dumbarton Oaks. After a prolonged illness, he died on March 3, 1943, having been unable to return to France due to the Second World War. Mildred Bliss was enormously fond of Focillon and close to both him and his wife. Two days after his death, she read this memorial tribute to those assembled in the Dumbarton Oaks Music Room:

Friday, March 5, 1943

4 o’clock

Dumbarton Oaks today is moved—very deeply moved. Maître Henri Focillon, its friend, will never again sit amongst us, radiating wisdom and charm and wit.

One’s memory sees him coming cautiously down these steps, his head stooped and to one side, and from under heavy lenses those clever and observing eyes seeing everything, while he deprecatingly says—“Ah! Madame—j’ai de si mauvais yeux—je ne vois rien.” But a moment later, still looking down, though pointing upward to a textile high on the wall—“Ah! La belle tapisserie copte—les Néréïdes, n’est-ce pas? J’aurai beaucoup de plaisir a l’étudier de plus près.”

Seldom has knowledge been disseminated with so gentle a touch; or wit been so kindly or instruction so enthralling.

Henri Focillon was the embodiment of the Mediterranean Culture, as expressed through the long and distinguished tradition of the humanistic discipline in France.

His nature, as capacious for right feeling as his brain for broad thinking, held unswervingly to his self-imposed loyalties. He abhorred cruelty, despised insincerity and had contempt for the meretricious in all its forms. Yet it was not because of his intense dislikes that the world recognized the strength of his unusual personality, but because of the integrities by which he lived. Kindliness and witty ridicule were his most devastating arms and he had never, I imagine, been defeated in a tilt.

With apprehensions so sensitive and analytical abilities so developed, he had the exceptional capacity for moral suffering which is the price that must be met by the intellectual and the aesthete.

The somber tragedy of his country bowed him down. Dumbarton Oaks cannot forget the physical battle for survival that Professor Focillon waged with his stricken heart—waged and won during two years of torment. A lesser nature would have been destroyed long since. But the wound was too deep—The Master groped through the black night which engulfs France and knew he would never see his land again. But though too late for him, he held the certainty of the rebirth of his race and the continuity of his nation.

Of Focillon’s scholarly activities I am not, alas, competent to speak. Professor Koehler, his colleague, whose gifts our friend greatly respected, will, I know, do justice to the results of a lifetime of great industry and constructive accomplishments. We, laymen, will remember him for his genius for stimulating the best within our poor selves, no longer barren under the spell of his radiating mellowness.

Dumbarton Oaks has had the rare privilege of being led by him—he lived among us, he shared our daily life and his wisdom and his smile are woven into the texture of our inheritance,—the rich inheritance of the Humanism of France, of which he was both the disciple and the master.

From the Thames to the Rio de la Plata, from Moscow and Leningrad to Constantinople and throughout the breadth of Europe, there was admiration for the scholarship and respect for the character of Maître Henri Focillon of the Collège de France—and of Dumbarton Oaks, where there is enduring affection as well.

Mildred Bliss

For a tribute to Henri Focillon by his former students, see here.