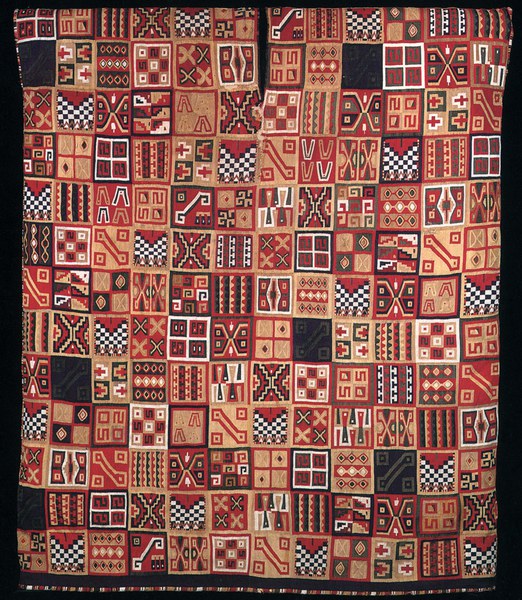

All T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, ca. 1450–1540, Dumbarton Oaks Museum, Pre-Columbian Collection (PC.B.518).

In the early decades of the twentieth century, “primitive” art, that is, non-European objects that lay outside the canon of what was then considered to be art, was becoming more visible, especially in the small antiquities shops in Paris. Like contemporary modern art of the time, such art—including Chinese, Egyptian, Islamic, Pre-Columbian, Byzantine, and African—was considered exotic, or as the art critic James Shapley put it when describing Byzantine art in 1931: “It is the unknown, beautiful, mysterious, distant, exotic, and even orphaned cultural other. Like an odalisque, its tenure on the affections depends on its capacity to remain perpetually different, inexhaustibly strange” (J. Shapley, “Byzantine Art in Chicago,” Parnassus 3, no. 8 [1931]: 29).

Those who liked this “exotic cultural other” undoubtedly did so because of its mastery of aesthetic forms, sensitivity to materials, freedom from naturalistic imitation, and boldness of abstraction.

Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss became admirers and collectors of this so-called “primitive” art. They had arrived in Paris in 1912 when Robert Bliss was posted to the U.S. Embassy there, and it was in Paris that Bliss acquired his first “exotic cultural other,” an Olmec jadeite sculpture. Bliss later wrote:

Soon after reaching Paris in the spring of 1912, my friend Royall Tyler took me to a small shop in the Boulevard Raspail to see a group of pre-Columbian objects from Peru. I had just come from the Argentine Republic, where I had never seen anything like these objects, the temptations offered there having been in the form of colonial silver. Within a year, the antiquaire of the Boulevard Raspail, Joseph Brummer, showed me an Olmec jadeite figure. That day the collector’s microbe took root in—it must be confessed—very fertile soil. Thus, in 1912, were sown the seeds of an incurable malady!

Unquestionably, it was Royall Tyler who was responsible for instilling in the Blisses a passion for the exotic art that was new to the marketplace in Paris. Already in 1909, he had written:

Art is much wider and more complicated than it was half a century ago. Modern foreign schools, the once despised periods of the art of the past, the arts of all the ages and all the nations, are biting and scratching in the space which was once reserved for the best-behaved Italians and Netherlanders, a few Frenchmen, Englishmen and Spaniards. The old rules can no longer be applied. No one is content to observe them.

—R. Tyler, “Essays on Masterpieces—I,” The Englishwoman 1, no. 1 (February 1909): 76–77.

Tyler continued to make the rounds of the Parisian dealers with the Blisses, and in the following years, they would acquire Caucasian, Sassanian, Islamic, and Byzantine objects. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, however, the supply of art to the Parisian dealers began to dry up and the Blisses turned their attention from collecting to aiding France and eventually the United States in the war effort. They would only be able to return to collecting in the 1920s and then only on their occasional return visits to Paris or especially through the advice of Royall Tyler, who continued to frequent the Parisian dealers and make recommendations to the Blisses on artworks to be acquired. (For more on the relationship between the Blisses and Royall Tyler, see the Bliss-Tyler Correspondence.)

Today, the Bliss Collection is best known for its Byzantine and Pre-Columbian Collections, which are prominently displayed in the Dumbarton Oaks Museum and which tangibly represent two of the research programs supported by the institution. However, the Blisses’ collecting interests were considerably broader. Their collection had significant holdings representing the art of the African, Chinese, Egyptian, Islamic, Persian, and Scythian cultures. The Blisses also collected paintings from the modern schools, including works by Degas, Daumier, Seurat, Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso. (Those artworks not belonging to the Byzantine or Pre-Columbian Collections are part of the House Collection.) Although widely disparate in culture and date, the art in the Bliss Collection, including the Byzantine and Pre-Columbian, is nevertheless united by its embodiment of the “exotic cultural other.”