Freer Gallery of Art

The Freer Gallery was the Smithsonian Institution’s first art museum and, along with the neighboring Sackler Gallery, holds one of the largest collections of Asian art and antiquities in the United States. The brainchild of the railroad magnate Charles Lang Freer, the gallery preserves Freer’s distinctive aesthetic vision.

I regard my collections as constituting a harmonious whole. They are not made up of isolated objects, each object having an individual merit only, but they constitute in a sense a connected series, each having a bearing upon the others that precede or that follow it in a point of time.

Charles Lang Freer

Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) was born in Kingston, New York, as the third of six children.Find out more about the Freer Gallery of Art on the Freer|Sackler website, http://www.asia.si.edu/, and explore their collections at http://collections.si.edu/search/. Freer’s father was a “disreputable” horse breeder and an inadequate breadwinner for his large family. His mother’s death in 1868 prompted the fourteen-year-old Freer to drop out out school to work in a cement factory.Thomas Lawton and Linda Merrill, Freer: Legacy of Art (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1993), 13.

Freer didn’t remain at the factory for long: his skill with arithmetic earned him a position as a clerk and bookkeeper at the town’s general store, next door to the offices of Kingston’s railroads. In 1870, he began working as a clerk at the New York, Kingston & Syracuse Railroad, which was then expanding its service to the entire Catskill Mountain region. By 1873, superintendent Frank J. Hecker appointed Freer accountant and paymaster for the entire railroad.Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac, The China Collectors (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015), 127.

Railroad Fever

Railroads across the United States were not only broadening their territorial reach but also reorganizing into ever-larger conglomerates. In 1876, Hecker took Freer with him to Indiana to oversee the consolidation of the Detroit, Eel River & Illinois Railroad.

Although the railroad deal that brought Hecker and Freer west eventually fell through, the two men remained in Detroit for the remainder of their lives. By the end of the decade, Hecker and Freer had organized the Peninsular Car Works, a company that produced the rolling stock needed to transport materials along the country’s growing rail network. Following a series of mergers, the conglomerated Michigan-Peninsular Car Company held a monopoly over the industry in Detroit by the 1890s; by the end of the century, the merger that created the American Car and Foundry Company gave Freer and his business partner a dominant share of the railroad car market east of the Mississippi River.Lawton and Merrill, Legacy of Art, 13–14.

Neurasthenia and Aesthetic Recuperation

By the time of his retirement from the American Car and Foundry Company in 1900, Freer’s net worth amounted to several million dollars. But his success had come at a cost. A failed attempt to merge the Wabash and Eel River Railroads in 1878 cost Freer his job and his health. He developed a nervous condition, “neurasthenia,” and he retreated to the Canadian woods to recuperate.Kathleen Pyne, “Portrait of a Collector as an Agnostic: Charles Lang Freer and Connoisseurship,” The Art Bulletin 78, no. 1 (1996): 78. Freer’s condition afflicted so many middle-class Americans of his generation that the psychologist and philosopher William James called it “Americanitis.” Brought on by stress and overwork, neurasthenia demanded a variety of treatments, from vigorous exercise and electric shocks to relaxation exercises and total bed rest. See Greg Daugherty, “The Brief History of ‘Americanitis,’” Smithsonian Magazine, March 25, 2015, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/brief-history-americanitis-180954739/?no-ist and G. M. Beard, The Nature and Diagnosis of Neurasthenia (Nervous Exhaustion) (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1879).

The same desire to escape the rigors of commercial life that sent Freer to the woods seems also to have attracted Freer to art and art collecting. Shortly after moving to Detroit, he became one of the founding members of the Detroit Club, an association of local notables who had contributed to the city’s new art museum. Little did he know that he was embarking on a journey that would ensure his legacy.Nichols Clark, “Charles Lang Freer: An American Aesthete in the Gilded Era,” The American Art Journal 11, no. 4 (October 1979), 56.

From the Detroit Club to Whistleriana

Populated by nouveaux riches, the Detroit Club and the Grolier Club in New York City served as fora for the cultural elite, patrons and artists alike. At these clubs, Freer befriended not only luminaries like the lawyer Howard Mansfield and sugar millionaire Henry O. Havemeyer, who would donate his art collection to Metropolitan Museum of Art, but also artists like stained-glass designer Louis Comfort Tiffany and the landscape painters Dwight Tryon and Thomas Dewing.Ingrid Larsen, “‘Don't Send Ming or Later Pictures’: Charles Lang Freer and the First Major Collection of Chinese Painting in an American Museum,” Ars Orientalis 40 (2011): 10 and Clark, “Charles Lang Freer,” 56.

Though little remembered today, Tryon and Dewing were disciples of the England-based James McNeill Whistler and were among the first painters whom Freer collected and publicly promoted.Clark, “Charles Lang Freer,” 58. But it wasn’t until a winter evening at Mansfield’s New York residence in 1887 that Freer first encountered Whistler’s work. After examining Mansfield’s collection of over three hundred Whistler etchings, Freer declared that he “had no words to express my admiration for the genius of this man.” Freer became an avid Whistler collector, eventually amassing the largest collection of his work in the world.Lawton and Merrill, Legacy of Art, 18.

Whistler and the Far East

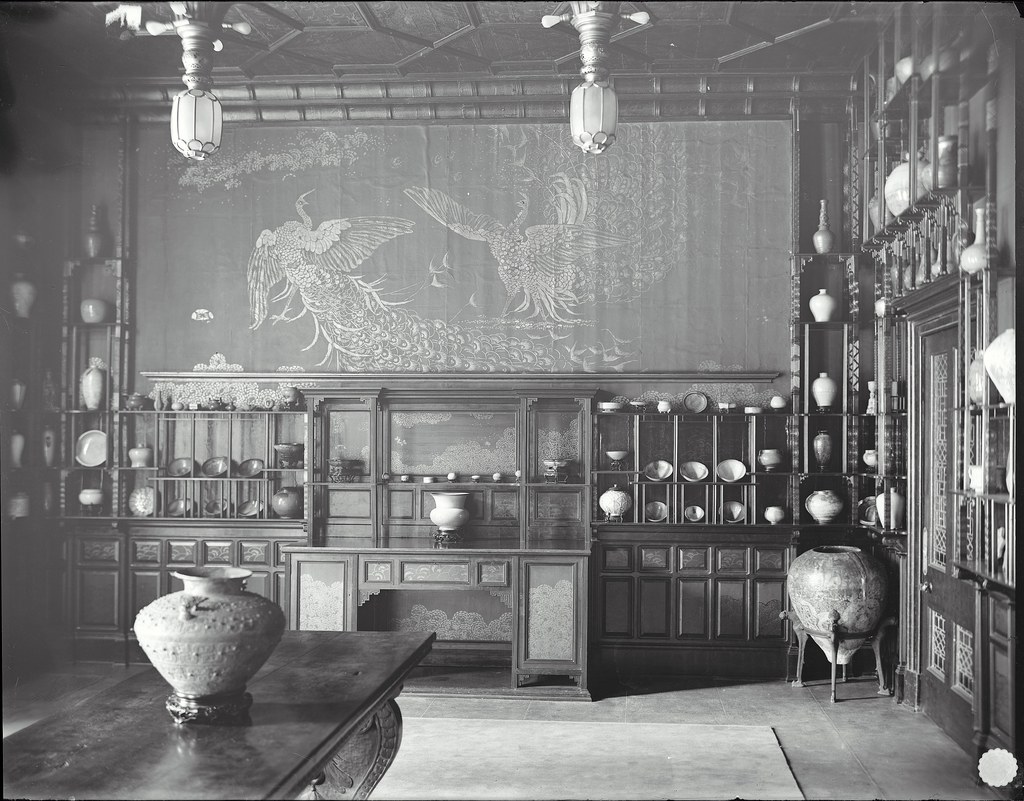

Freer and Whistler first met in London in 1890, striking up a close friendship that would last for the remainder of their lives. Upon meeting Whistler, Freer resolved to build a comprehensive collection of the artist’s work and, after Whistler’s death, covertly purchased the famed Peacock Room for display at his Detroit residence.

At Whistler’s suggestion, Freer began collecting art and artifacts from Asia and sought to trace the influence of ukiyo-e artists like Hiroshige and Hokusai on Whistler’s work.Larsen, “‘Don’t Send Ming or Later Pictures,’” 10.

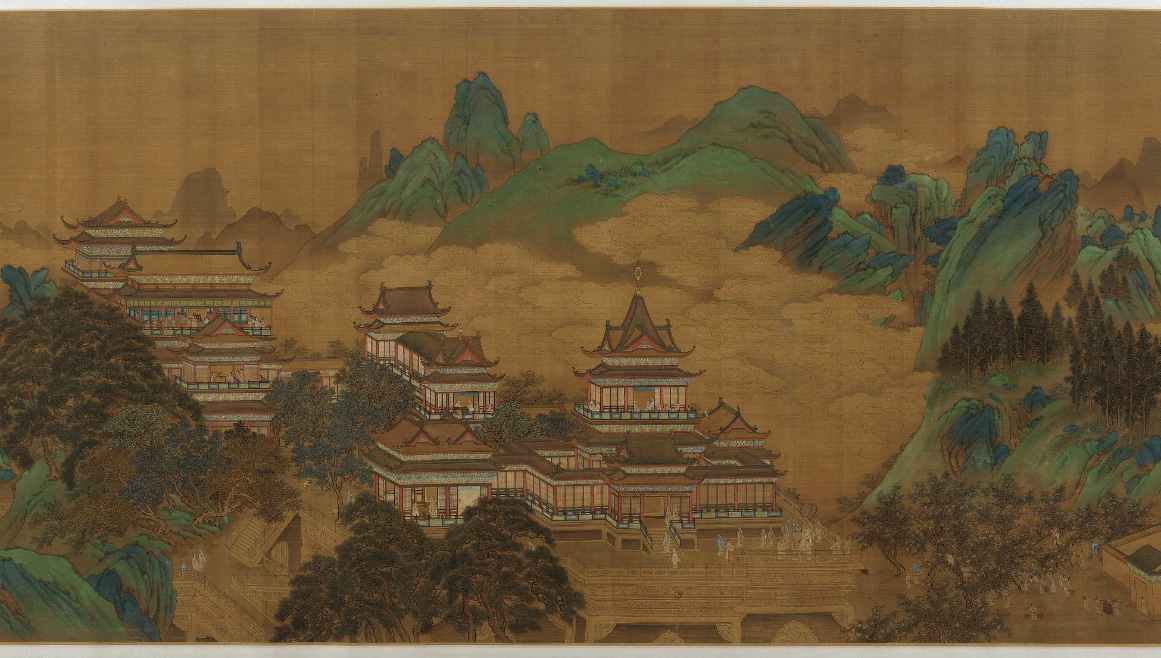

Committed to a universal and “art for art’s sake” theory of aesthetics, and guided by Whistler and other specialists in Asia such as the philosopher of art Ernest Fenollosa, Freer became an avid curator. He assembled a collection of over nine thousand objects by the end of his life. Concentrating on Chinese painting from the Tang to early Ming, Japanese painting of the Edo period, and pottery and ceramics produced in the Near and Far East—all complementing nearly a thousand Whistler paintings, drawings, and etchings.Material Papers Relating to the Freer Gift and Bequest (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, February 8, 1928), 4 and Linda Merrill, With Kindest Regards: The Correspondence of Charles Lang Freer and James McNeill Whistler 1890–1903 (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1995), 42.

As Fenollosa later noted, “This collection strikingly illustrates the most conspicuous fact in the history of art, that the two great streams of European and Asiatic practice, held apart for so many thousand years, have, at the close of the nineteenth century, been brought together in a fertile and final union.”Ernest C. Fenellosa, “The Collection of Mr. Charles L. Freer,” Pacific Era 1, no. 2 (November 1907): 59.

The Meeting of East and West

The union of East and West was not merely aesthetic. The Opium Wars and the construction of the Suez Canal in the 1860s had opened China and Egypt to the Western world as never before. Along with the destabilization of local regimes (the Qing Dynasty collapsed in 1912, the Ottoman protectorate in 1914) came the growth of the local antiquities trade. Dealers such as C. T. Loo, who sold Freer some two thousand objects worth nearly a million dollars, and Dikran Kelekian were able to capitalize on this convergence of external interest and internal unrest to set up export shops in Cairo, Shanghai, Paris, Istanbul, London, and New York.Lawton and Merrill, Legacy of Art, 111–12 and Meyer and Brysac, China Collectors, 136.

In addition to cultivating close relationships with dealers, Freer embarked on five trips of his own: to Japan to study Buddhism in 1894, and to Egypt and China in 1906–7, 1908, 1909, and 1910–11 to hunt for paintings and artifacts not available at home.Lawton and Merrill, Legacy of Art, 59 and Meyer and Brysac, China Collectors, 130. Often posing as an agent for an American dealer, Freer acquired some of the most valuable objects in his collection on these expeditions, including Coptic manuscripts of the Gospels and Psalms and the Song dynasty handscroll Ten Thousand Li Along the Yangzi River.Ann C. Gunter, A Collector’s Journey: Freer and Egypt (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2002), 103 and Larsen, “‘Don’t Send Ming or Later Pictures,’” 19. Though poor health and political instability would eventually put an end to Freer’s collecting expeditions, he continued to acquire shipments, often in bulk, from his dealers until the end of his life.

Collecting for Posterity

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Freer began to consider his collection’s legacy. Whistler’s own fame had increased between 1877, when the English critic John Ruskin had derided Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold as “Cockney impudence,” and the artist’s death in 1904.Lawton and Merrill, Legacy of Art, 39. Freer, however, hoped that his collection would disseminate to a wider public the appreciation of Asian art necessary to understand Whistler’s peculiar genius.

Freer had no natural connection with Washington, D.C., but he “envisaged the capital as a growing center of tourism, and therefore as the real fulcrum for educating the American people.”Agnes E. Meyer, Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 1970), 13. His initial proposal in 1904 to the board of regents of the Smithsonian Institution, however, was met with cool disinterest. The Smithsonian had never managed an art museum, and Freer’s idiosyncratic collection seemed an unorthodox place to start.

President Theodore Roosevelt, however, thought otherwise. Roosevelt understood Asia’s immense geopolitical and cultural importance—he had overseen the construction of the Panama Canal, negotiated the treaty ending the Russo-Japanese War, and envisioned the expansion of American naval power to the Pacific—and he intervened on Freer’s behalf in December 1905. The Smithsonian acceded to Freer’s terms within the month.Meyer and Brysac, China Collectors, 132–33.

The Freer Bequest

Freer gave nearly his entire collection to the Smithsonian, which included a thousand Whistlers; three thousand Chinese and two thousand Japanese paintings, jades, and porcelains; and another three thousand pottery and stoneware objects from the Near and Far East. He also provided $500,000 for the construction of a new museum on the National Mall, and another half million dollars for its endowment in perpetuity.Material Papers, 1.

The museum building, designed in the Italian style by the architect Charles A. Platt, reflected Freer’s particular vision for the display of his collection: one hallway of the gallery would hold Japanese art, the other Chinese. The latter would culminate with Whistler’s famed Peacock Room, which Freer arranged to have transported from his Detroit residence. Whistler’s other works would find a permanent home in the back rooms of the gallery. An interior garden and collection of study objects curated by Freer himself were integral to Freer’s original plans, but were ultimately rejected as infeasible.Meyer, Charles Lang Freer, 11.

Freer placed profound constraints upon the further development of the collection itself. In order “to maintain the harmony of the collections to which I have given so much attention,” Freer stipulated that the collection could never be exhibited outside the building, nor added to or subtracted from after his death.Lawton and Merrill, Legacy of Art, 186. Though he set aside funds for expanding the Near Eastern and East Asian collections, all additions after his death were subject to the approval of Freer’s close friends: Eugene and Agnes Meyer; Louisine Havemeyer, widow of Henry O. Havemeyer, and the architect Charles A. Platt.Meyer, Charles Lang Freer, 14.

Founding the Freer

Although the Smithsonian accepted Freer’s terms in 1906, gallery construction was interrupted by the First World War. Freer’s health steadily worsened throughout the war, but he continued to acquire objects—worth nearly $1 million in all—from C. T. Loo until the day he died.Meyer and Brysac, China Collectors, 136. Freer also charged Langdon Warner to examine the possibility of establishing a school of archaeology and a national museum in Beijing. Though it was welcomed by Yuan Shikai, the president of the new republican government, the endeavor came to naught amid the chaos of civil war.Meyer and Brysac, China Collectors, 138–39.

Freer never lived to see his gallery completed; he died in 1919 after a long decline.Meyer, Charles Lang Freer, 21. He had made no plans for naming his gallery, nor did he wish the museum to broadcast his central role in its conception. It nevertheless opened in 1923 as the Freer Gallery of Art—fittingly named, as one acquaintance observed, for it was indeed “Mr. Freer’s Autobiography.”Lawton and Merrill, Legacy of Art, 235.

A Century of Asian Art

In the century since it first opened its doors, the Freer has remained a fixed mark in a constantly shifting world. Whereas in the 1890s, only a few institutions, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, were displaying Asian art, within a decade of the Freer’s inception, some fifty museums had acquired or were building substantial collections. Under the directorships of John Ellerton Lodge and Archibald Wenley, the Freer Gallery’s trustees and directors grappled with questions concerning the proper interpretation of Freer’s idiosyncratic will, even as the curatorial staff and technical laboratories they established transformed Freer’s private collection into a public museum.Thomas Lawton and Thomas W. Lentz, Beyond the Legacy (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 39–45.

When America entered the Second World War, Freer administrators removed the entire Japanese wing for storage amid fears of bombings and anti-Japanese sentiment.Lawten and Lentz, Beyond the Legacy, 42–44.

Freer | Sackler

In 1979, the constraints of Freer’s will, which resulted in a lack of objects from Korea and Vietnam and an underdeveloped South Asian collection, prompted the Japanese and Korean governments to pledge funds for the construction of an annex for traveling exhibitions and a rotating collection.

Within five years, plans for an annex to the Freer collection had expanded to a call for a coequal museum of Asian art adjacent to the Freer. Underwritten by the pharmaceutical billionaire and philanthropist Arthur M. Sackler, the Sackler Gallery, completed in 1987, did not have the same constraints that had stymied the Freer and allowed for works from the Freer to be displayed alongside recent acquisitions.

Though physically distinct, the two museums have shared directors and curatorial staff since the Sackler’s inception. Together they present two contrasting visions of Asian civilization, preserving Freer’s turn-of-the-century vision of the aesthetic relations between East and West and enabling curators to capture manifold visions of Asia’s past, present, and future.

Profile by Melda Gurakar, Melissa Rodman, Joy Wang, and Leah Yared, 2016 summer interns.