Authors, particularly those without a personal income or a wealthy patron, could seldom afford to publish their own illustrated books. The expense of commissioning an illustrator, in addition to an engraver, and of the printing itself—which was rarely done in the same printing shop as the letterpress printing and required different equipment and expertise—demanded money upfront. In some cases, a wealthy patron could fund the project outright, as with Linnaeus's Hortus Cliffortianus of 1738, which was financed by George Clifford, and which celebrated his garden at Hartekamp. Clifford was portrayed on the frontispiece of that book.

Another solution was to publish by subscription. This entailed having interested parties promise to buy the books. For instance, the first illustrated edition of John Milton’s Paradise Lost was published by subscription. The list of subscribers at the beginning of the book includes more than five hundred individuals. Subscription publishing was an effective means of securing finances for a book and, for authors such as Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), it was often the only way to publish an extensively and beautifully illustrated volume. Merian courted a wide network of subscribers, offering a reduced price for those who purchased her Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium in advance. Those who subscribed would receive her book for fifteen Dutch guilders while those who purchased the book after publication would pay eighteen guilders.

The illustrator Georg Ehret (1708–1770) also published by subscription. In contrast to Merian, his series of lavish botanical illustrations, Plantae et papiliones rariores, was published plate by plate over a period of ten years. Ehret had often provided illustrations for the publications of other authors, including Linnaeus, but he wished to publish a set of plates of his own design and specifications. Two of the plates contain dedications to individuals who had subscribed, including the Duchess of Portland.

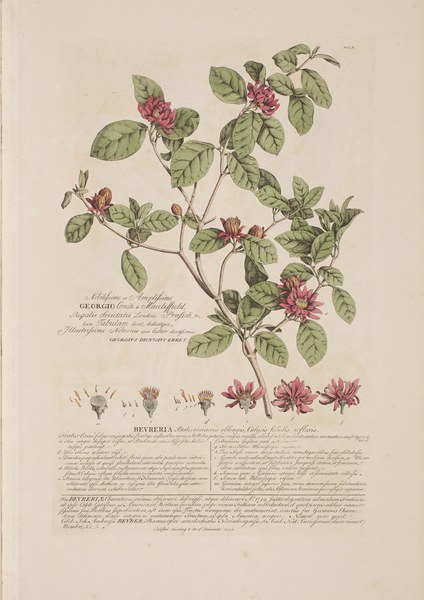

Often a list of important subscribers was published in the front of the book, as in the case of Richard Bradley’s A philosophical account of the works of nature (1721), Mark Catesby's The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama islands (1731–1742), and William Curtis’s Flora londinensis (1777–1798). In other cases, each plate was dedicated to a different patron, as is the case with Ehret’s plates. John Martyn’s Historia plantarum rariorum was also published in this fashion. Each of his botanical plates contains the name and heraldic crest of the individual or institution which subsidized his publication; see, for example, the lower right corner of the geranium illustration in Plants for Profit. The first plate is dedicated to Hans Sloane, the President of the Royal Society.

Subscription lists and dedications are evidence of eighteenth-century scientific networks. But it is worth keeping in mind that people would subscribe to a book for a variety of reasons. Some patrons no doubt wished to have their names associated with the other subscribers on the list at the front of the books. Others may have wanted to return favors or may have wished to have their own works promoted by the author when they themselves published in the future. Still others would have fit the stereotype of what we usually think of in the context of subscription publishing – a desire to promote botanical studies and collect beautiful images and books.

The networks that lay behind subscription lists were often much more complicated than a simple list of wealthy patrons. For example, Maria Sibylla Merian collected and courted subscribers by exchanging the many natural historical specimens which she brought back from Surinam and sourced from Amsterdam merchants. Although Merian was unable to join scientific academies, she was able to enter networks of correspondence, trade her knowledge, and gain more subscribers for her publication. Her correspondence with the Englishman James Petiver reveals just such an exchange. Merian sent Petiver drawings and specimens, requesting that he find subscribers for her in England. Petiver then displayed her drafts to the members of the Royal Society and placed an advertisement for her in the Society’s publication, Philosophical Transactions. This kind of interaction opened up Merian’s work to a market of subscribers with which she would normally not have had contact. Merian’s nuanced relationship to her subscribers reveals that subscription lists often contain relationships that are quite complex. In many cases, of course, they reflect contemporary systems for the exchange of natural historical knowledge and objects.

Bibliography

- Blumenthal, Hannah. “A Taste for Exotica: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium.” Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture 6, no. 4 (Fall 2006): 44–52.

- Gaskell, Roger. “Printing House and Engraving Shop. A Mysterious Collaboration.” The Book Collector 53, no. 5 (2004): 213–51.

- Kinukawa, Tomomi. “Natural History as Entrepreneurship: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Correspondence with J. G. Volkamer II and James Petiver.” Archives of Natural History 38, no. 2 (2011): 313–27.

- Seares, Margaret. “The Composer and the Subscriber: A Case Study from the 18th Century.” Early Music 39, no. 1 (2011): 65–78.

- University of Pennsylvania. "'Agents Wanted:' Subscription Publishing in America. A Brief History of Subscription Publishing." http://www.library.upenn.edu/exhibits/rbm/agents/case2.html (accessed November 22, 2013).