James N. Carder

“A Jewel Box of a Museum.”

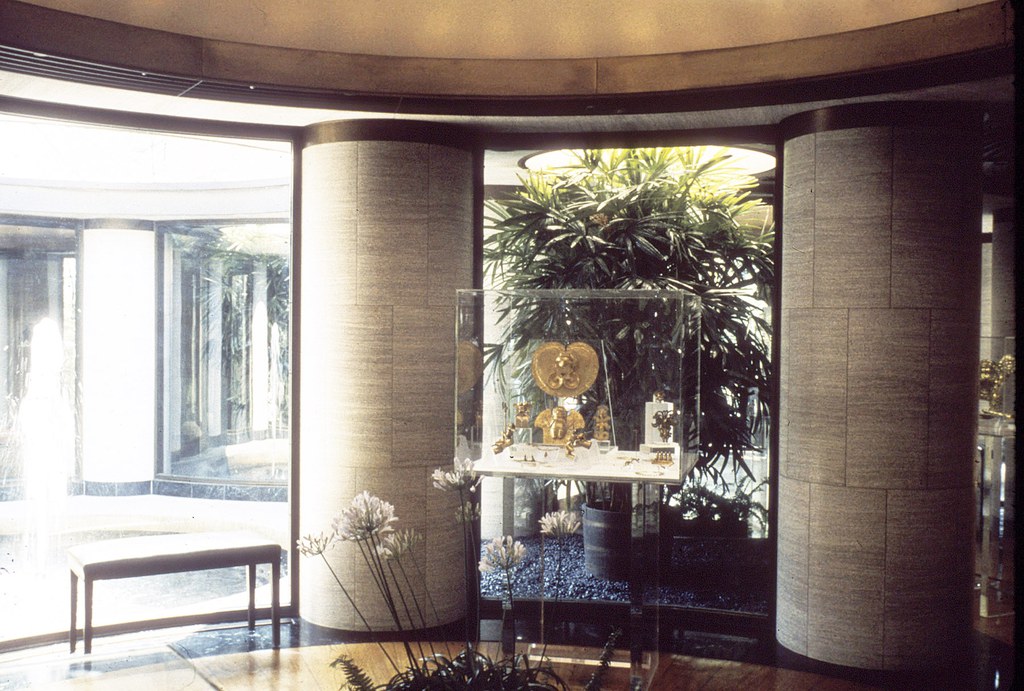

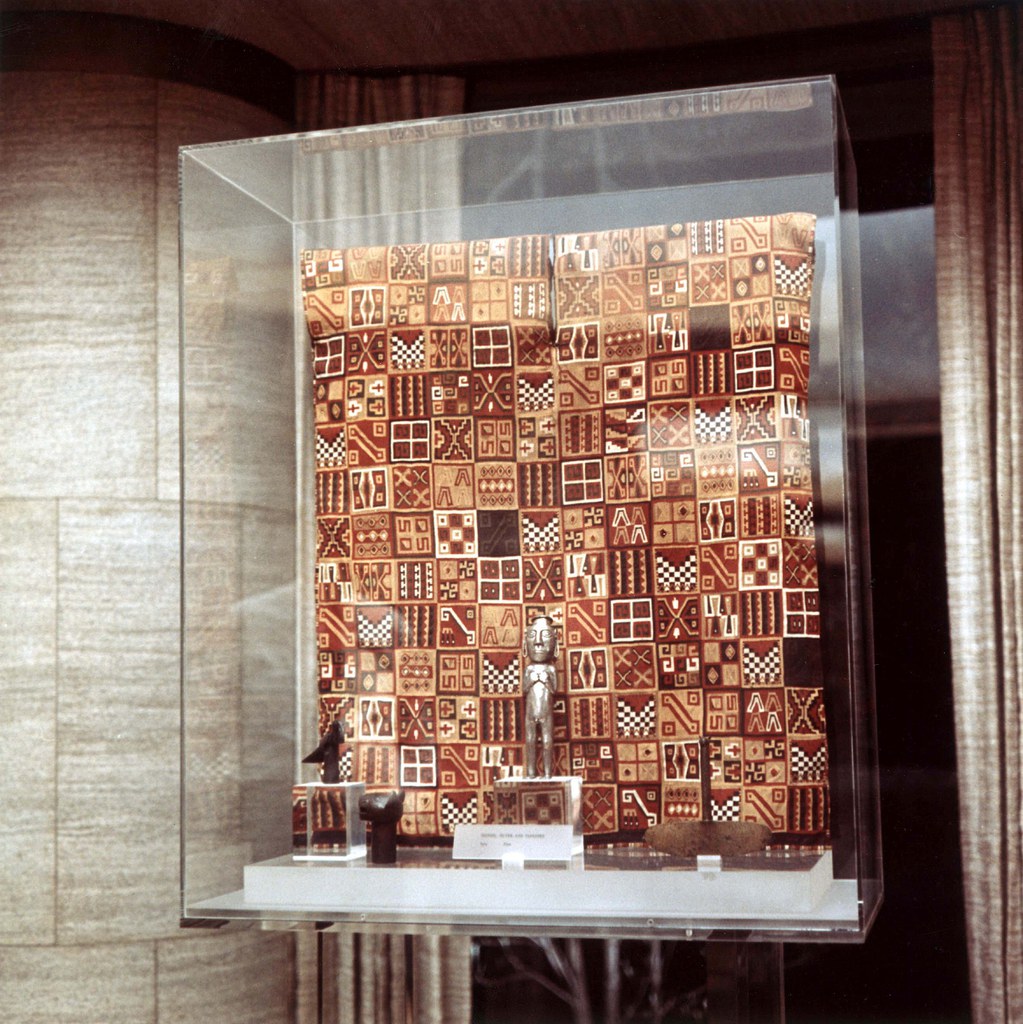

The Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art and its new gallery were first seen by invited guests at a preview opening on Saturday December 7, 1963, at 5:30 p.m. (fig. 30). The opening was purposely subdued due to the recent assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. The collection opened to the public the following Tuesday and thereafter between 2:00 and 5:00 p.m. Journalists, architectural historians, and architects who reviewed the building were fairly consistent in their opinions and in their praise. They found the building beautiful and the collection beautifully installed (fig. 31). They admired the understated use of high-end materials (marble, bronze, and teak) in a modern design as well as the visual contrast of the gold, jadeite, and textile objects in this setting. Many, although not all, found the scale and treatment of the building and the use of small galleries appropriate to the small scale of most of the exhibited objects. One reviewer exclaimed that, “for all its sumptuous elegance, the Dumbarton Oaks pavilion is actually humble. All of Johnson’s great skill is directed toward providing a reverent setting for exquisite works of art in an exquisite garden. . . . The design was determined by the scale and nature of the objects within. Here [the architecture] enhances the displays as the right frame enhances a good painting.”Wolfj Von Eckardt, “Dumbarton Pavilion’s Scheme.” Another reviewer wrote: “The detail work is unobtrusively luxurious,” and went on to compare the artistic nature of the building to the artistic nature of the Collection, informing the readers that Robert Woods Bliss had “built the collection strictly along lines of beauty, not ethnology or archaeology.”Frank Getlein, “Dumbarton Oaks Exhibit Reopens, New Bliss Art Pavilion Is Pure Delight to Eye and Ear,” Washington Star (December 10, 1963). The art critic Frank Getlein, writing in The New Republic echoed this sentiment and stated: “For such material [i.e., Pre-Columbian objects] the building is a beauty, not only making such attention easy but echoing the fascination of the objects in itself. There is no competition between the container and the things contained, yet it is entirely possible to experience and delight in the building even as it leads the body and eye to object after object in the collection. . . . What I am getting at is that every single prospect pleases in itself and every one is on the small, intimate scale of the works in the exhibition.”Frank Getlein, “Model Museum: Glass at Dumbarton Oaks,” The New Republic (December 28, 1963), 28.

In these many reviews, the preciousness and sensuousness of both the building and the collection are frequently referenced, often by referring to the building as a “jewel box.”The building was also referred to as a “jewel” or a “gem,” as, for example, the statement: “The new wing is a delicate gem—a modern glass and stone museum of intimate size and limitless scope, blending the simple flowing circles on the interior with the intricate foliage patterns of the outdoors.” Nona B. Brown, “‘A Timeless Place,’ Dumbarton Oaks in Nation’s Capital is a Storehouse of Treasures,” New York Times (May 24, 1964). Ada Louise Huxtable, the venerable architectural critic of the New York Times, was perhaps the first to do this. She introduced the building by stating: “Small. Elegant. Its contemporary style has been planned to complement, rather than copy, the Georgian-style mansion to which it is connected by a simple corridor. The effect is of ancient treasures in a modern jewel box.” She continued:

[Philip Johnson] is the perfect man for the job because a museum ideally, is a total esthetic experience: a balance of art with architecture on the highest level of controlled, sensuous pleasure. Mr. Johnson’s sense of beauty might be said to be on perfect pitch. There is restrained use of the richest and most luxurious materials for maximum impact without ostentation; form is an elegantly experimental game serving artful purposes with extraordinary finesse; and above all, there is impeccable taste.Ada Louise Huxtable, “Pre-Columbian Art Exhibition Opens New Museum in Capital,” New York Times (December 10, 1963).

She noted that the chosen materials and colors were muted, that the bronze, teak, fine-grained Illinois marble, and the green Vermont marble were “extravagantly luxurious,” but that the scale was delicate, even miniaturized.Ibid.

The architect and bookbinder Stanley M. Sherman, writing in the American Institute of Architects Journal, echoed Huxtable’s commentary. He called Johnson’s building a “little jewel box of a museum to house Mr. Bliss’ collection of Pre-Columbian art,” and saw it as “a building little like any other in a setting unlike any other.”Sherman, “Uncommon Ground,” 36. He noted that the museum utilized materials and form in a rare combination, i.e. the employment of “costly materials in a seldom-conceived arrangement” which heightened “the impression of wealth in a relatively small space, which is a common reaction at Dumbarton Oaks.”Ibid., 38.

This praise notwithstanding, and in contrast to other reviews, both Sherman and Huxtable had suspicions that Johnson’s architecture might overwhelm the collection it was designed to house (fig. 32). Sherman, who may not have appreciated Pre-Columbian art, wrote that “the pre-Columbian artifacts are not only small but in many ways remote as objects of interest, except to those with inordinately sensitive tastes or specialized knowledge. They speak of a time and place that has little in common with the here and now. The ordinary reaction is to observe the enclosure and not the things enclosed. Even the teak floors, carefully cut as spokes of a circle, with green Vermont marble surrounds, are more often observed and commented on than many of the ostensible exhibits of the museum.” The larger question for Sherman was “whether a museum should be primarily an enclosing frame or a work of art in its own right.”Ibid., 40. Although this question remained unanswered by Sherman, Philip Johnson had already vigorously argued for the museum as artwork in an article of 1960.Philip C. Johnson, “Letter to the Museum Director,” Museum News 38 (January, 1960): 22–25. Huxtable expressed her suspicions more amusingly and tentatively. She wrote:

In spite of its subtlety, however, the architecture has a quiet insistence that has made installation almost as difficult as at the Guggenheim [designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright]. There, it is a screaming fishwife fight between building and contents, with victory only to a determined director. Here [at Dumbarton Oaks] it is a delicate duet in which the architecture, always as strong as the art, never retreats or submits. The art has had to be carefully accommodated to it. . . . [with] an installation that uses only plexiglass stands and vitrines, the closest approach to invisibility. Whether this is successful is questionable. It succeeds in putting the emphasis on the magnificent objects of stone, jade, pottery and gold on display, but it also has something of the air, with the round rooms and columns, of a Paris style moderne parfumerie of the nineteen-thirties, only the mirrors and the models in marabou are missing.Huxtable, “Pre-Columbian Art Exhibition.”

Along similar lines, an unnamed reviewer in Architectural Forum found that, “unhappily, the building is so delightful that it competes with the pre-Columbian art; and the designer of the display racks here gave up, capitulated, tried to make the cases disappear. So the building wins.”“Pre-Columbian Art in a Post-Modern Museum,” Architectural Forum 120 (March 1964): 110. Similarly, the unnamed reviewer in Architectural Review observed that “[t]he relationship between setting and exhibits is felt to be unhappy—the setting certainly seems to smother them.” He or she qualified this by adding: “At a second or third visit the exquisiteness of the art-works might well take command, experience alone will tell.” “Philip Johnson and Post-Modern Architecture,” Architectural Review 136 (July 1964): 4.

In his early review of the building, Robin Boyd singled out Johnson’s creation of a “witty” spatial environment, what he called Johnson’s demonstration of “how to have fun with space,” situated in a “courtly and formal” manner within its environment:

It was a folly, a garden ornament, a small pavilion of extraordinary richness for this century, made to exhibit a few dozen pieces of Pre-Columbian art. An exemplar of brain-wave design, its plan consisted of nine circles stacked into a square, three rows of three, with the centre one removed to form an open space. The theme of the circle permeated everywhere. There were no walls as such, but rich plump cylindrical columns and curved glass walls. Each of the eight circular cells was rooted with its own little dome. It was perhaps the least functional building erected since the Albert Memorial, and as full of wanton delights, but delights of this century. The sense of interior space was intimate, unique and appropriate to the exquisite and sumptuous nature of the project. The space did not flow so much as it pranced elegantly from one cell to the next, and hopped in and out of the humanly-inaccessible central court where a heavy jet of water spilled over black stones. This was witty space, but at the same time as courtly and formal as the exterior of any second-phase building.Robin Boyd, The Puzzle of Architecture (London and New York, 1965), 149–50.

Of interest is the fact that none of the reviewers of Johnson’s building found fault with or objected to his use of modern design, even in the context of the “historical” Georgian architecture at Dumbarton Oaks. In fact, the Washingtonian Wolfj Von Eckardt recounted that “as the building went up, some Georgetowners grumbled that such an unusual structure—and a contemporary one, at that!—should be hidden from view. Now some of the same people grumble that the wall and thick planting on 32d St. all but cover a structure they have come to admire.”Von Eckardt, “Dumbarton Pavilion’s Scheme is Inside Out.” Ada Louise Huxtable concluded her review by writing: “The problem of relating the new wing to the old building which is the famous seat of Byzantine studies of Harvard University, has been handled with singular skill. It is an object lesson in how not to compound the error of reproducing reproductions of 20th century versions of 18th century buildings, which become increasingly moribund as the process continues. The Georgian style house is joined suavely to the handsome, contemporary gallery, and the whole is more than the harmonious sum of its parts.”Huxtable, “Pre-Columbian Art Exhibition.”